Black Americans in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula – Part Two

“Rural Voices” shares cultural, educational, economic and artistic views of people who have lived and thrived in the Upper Peninsula. Each of our authors in Rural Voices may be living here in the U.P. or living someplace around the globe, but the U.P. is an important part of who they are and what their beliefs and values are today. Rural Voices wants to share the voices of our neighbors and friends about life and experiences in the UP.

PART 2: 1850 to 2021

Early American Occupation, Post 1796

According to the terms of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which ended the American War of independence, the western boundary of the United States was the Mississippi River. However, the British, wishing to exploit the fur-rich Great Lakes region, refused to evacuate the country. After lengthy negotiations between American and British commissioners, Jay’s Treaty was ratified in 1794. One article called for the British to evacuate the region and a lesser known article directly affected the institution in the Great Lakes region: “All settlers and traders shall continue to enjoy unmolested, all their property of every kind. It shall be free to them to sell their houses, lands, or effects or to retain the property there at their discretion.” Although this treaty seemed to violate the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 which prohibited slavery northwest of the Ohio River, the original settlers in the region were allowed to retain their slaves since they were considered private property. Michigan’s territorial judge, Augustus B. Woodward in Detroit mandated that no new slaves could be introduced into the territory and gradually those who remained would either be emancipated or die so that by 1837 when the new constitution was created there were only three slaves in the state.

Many of the descendants of Africans who had been brought into the region during the colonial era continued to reside there. The aforementioned Bonga family is a good example of this. According to the Federal census of 1810, there were 4,762 people in Michigan Territory and this figure included 120 free Africans and twenty-four slaves. In Michilimackinac County, which included the entire Upper Peninsula and all the territory westward to the Mississippi River, there were 615 people residing along with fifteen Africans and one slave. The census taken a decade later showed the white population increasing to 819 and there were only five free Blacks. During these years, prior to the discovery and exploitation of copper and iron in the Upper Peninsula, which stimulated a population boom, the number of Blacks remained small. In 1830 there were only five and ten years later there were six.

Decades prior to 1850

During the decades prior to 1850 there is little information available concerning Blacks living in the Upper Peninsula. However, in 1825 at Sault Ste. Marie there was a contested election for a territorial representative and in the ensuing debate and investigation there were some interesting facts which were revealed. The question to be answered was whether or not métis could vote in these elections. The métis included issue from White-Indian unions and Black-Indian unions as well. To the whites at Sault Ste. Marie, these mixed bloods were considered second-class citizens. One person in this class who had voted was described as one “who by the testimony appears to have descended from “Indian and Negro parents.” Once the debating was concluded it was decided that it was illegal for Native American and Blacks and métis to vote, so the fellow’s vote was not counted. This is an interesting and little known case of racial discrimination in a Federal election on the northern frontier.

The number of Blacks and the population in general did not increase until the mid-century with the opening of copper and iron mines. By 1850 there were fifty-two Blacks living throughout the Peninsula. There were thirty-seven in Mackinac County, eight living in Sault Ste. Marie, six in Ontonagon County, and one at Eagle Harbor.

We find a number of Blacks living in the Upper Peninsula from Border States like Missouri and Kentucky who might have been runaway slaves who headed north and into the wilderness where slave hunters would find it difficult to find them. In Ontonagon County, twenty-nine year old, Noel Johnson from Missouri and his wife, Mary Ann from Delaware, a slave state were farmers with two children who has been born in Michigan beginning in 1846.

Serving Public Transportation

We have scant information about African Americans working on steam boats in the waters of the Upper Peninsula. William Monroe shows up as a cook at Sault Ste. Marie listed with sailors which might indicate that he was a cook on a ship. In Late October 1856 the steamboat, Superior was sunk in a storm off Pictured Rocks and newspapers carried the names and occupations of the living and dead. There were two colored waiters who probably were brothers: Alexander and Thomas were among the dead along with Robert a “colored cook,” Burd a “colored sailor,” and John a “colored fireman.” This provides us with an inkling of African Americans who regularly served on lake steamers and have never been counted.

African American continued the tradition of serving on public transportation especially the railroads. They served as porters, waiters and cooks and provided excellent service. At the end of the line in the Upper Peninsula they had segregated clubs and sleeping accommodations at terminal points like Sault Ste. Marie and Champion. For the Black rail crews there were Sundown locations like Ironwood in the western Upper Peninsula, where Black crew were forbidden to even step off the train onto the platform for a smoke or to stretch their legs. The police wait any malefaction.

Migration from the South

As the decade passed a number of fugitive slaves from the South migrated to the Upper Peninsula feeling that they could be protected by the isolation of the region from slave catchers. By the eve of the Civil War there were approximately one hundred and sixty Blacks in the region but this number declined a decade later when slavery was ended and African Americans were free to live in lower Michigan.

In the isolated and remote Keweenaw Peninsula in July 1863 four Black entertainers arrived at Clifton having taken a steam to get there. They had a program of songs and dances that attracted miners and their families who were starved for different and outside entertainment, all for a 25 cents admission fee.

Mackinac Island

Mackinac Island once home to African Americans since the French era, became a tourist mecca beginning in the 1830s. Hotels and restaurants developed to accommodate visitors from across the United States many seeking to avoid hot humid weather and accompanying diseases like yellow fever and malaria especially from the South. In the summer of 1860, Edward Frank, a hotel keeper hired a Black staff of cooks, waiters, washerwomen, coachmen and porters. Many of them were from border states like Kentucky and Virginia and were probably former slaves who traveled north along the Underground Railroad. Also at this time at the other resort center, Sault Ste. Marie, Isaac Payne and his family were from Virginia and the District of Columbia. Isaac was employed as a cook.

The one hotel on Mackinac Island that continues to hire a large Black wait staff is the Grand Hotel. It was opened in July 1887 and was a summer retreat for visitors who arrived by lake steamers and rail from across the country. Five president, inventor Thomas Edison and author Mark Twain have all stayed or visited the hotel. Since its opening the Grand Hotel has hired African Americans and in 1890 there were 220 Blacks working at the hotel, three years after it opened. It continues this tradition especially with its wait staff that is composed of Jamaicans. However not all guests are pleased with the situation of an all-black wait staff:

Still Trying To Keep America’s Racist Past Alive

Review of Grand Hotel. Reviewed July 10, 2018. Stayed June 2018.

In the 21st Century it is utterly ludicrous that a hotel like this is even allowed to operate as it does. This was nothing but a grandiose place imitating the racist past of America. White people go here so they can reminisce about how it used to be with hopes that we will go backwards. This place allows them to bask in the hideous and racist past of America. Dream on…. because in 2025, this will come to an end. America will finally become the land it should have always been… one for ALL people of ALL ethnicities.

G.H. Kellie, Manager at Grand Hotel, responded to this review on July 11, 2018.

Thank you for your comment. We are sorry the wait staff at Grand Hotel has made you feel uncomfortable. Grand Hotel has a staff of over 700 employees from 27 different countries and works with several colleges and universities. Before we can hire anyone from outside of the United States, we are required by law to obtain permission from the State of Michigan, US Department of Labor and the United States Customs and Immigration Service. Our annual efforts to find American labor are extensive and costly, but very important to us. For these reasons and because we can only offer seasonal employment, we have been unsuccessful in hiring an all American staff. Regardless of their skin color we hire qualified individuals who we know will do the best job possible in serving our guests. Thank you for choosing Grand Hotel and we hope you will consider a return visit in the future.

Across the UP in the 19th Century

Across the Upper Peninsula African Americans were to be found usually associated with service industries, barbers being a major occupation. In Houghton and Marquette counties with the largest populations has 173 African Americans in 1880 and 410 a decade later. Little known is the fact that some African Americans settled in the UP as farmers. In 1900 there were thirty-four farm owners and three tenant farmers. Others played important roles in the communities they lived in. Joseph Smith (1851-1928) was born in the province of Ontario and settled in Marquette in 1877 as a barber. His special talent was organizing, managing and promoting sporting events in Marquette and at the county. He is best known for organizing dog races in Marquette on Washington’s birthday holiday for many years. Samuel Noll was born a slave in Virginia, killed his overseer and fled via the Underground Railroad to Detroit. He settled in Marquette and at the turn of the 20th century he worked closely with George Shiras III who was pioneering night photography of animals. The Jamaican, George Preston (1846-1920) first settled in the Copper Country and went to Marquette in 1865.He first operated a barbershop then developed a confectionery and later a restaurant. His daughters Charlotte and Bessie were in the first class at Northern State Normal School (now Northern Michigan University) in the fall of 1899. Charlotte “Lottie” (1881-1901) would have been the first graduate of color from Northern is death by consumption had not intervened. Her sister Bessie Madeline (1883-1904) received her teaching certification in 1903 and went on to teach mathematics at Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute, but died thirteen months later.

The last prominent African American in Marquette was William Washington Gaines (1823-1903) whose name is commemorated in the city by Gaines Rock along South Lakeshore Blvd. He was the son of Virginia ship builder Pitt Gaines and his slave Nancy Wheatley and was given his freedom upon reaching adulthood. He went on to purchase the freedom of Mary the woman he loved and after marrying settled in the Upper Peninsula. They settled in the Copper Country where Gaines worked as a copper miner where cave-ins, dust and explosions posed risks to life and limb. Injured by falling rock Gaines ended his time as a miner and in 1855 the family moved to Marquette. He was employed as a coachman and groundskeeper by Heman B. Ely, a local businessman whose home was located on Lake Superior near Whetstone Creek. The Gaines family first lived in the attic of the home before they built their home at a nearby granite promontory, now Gaines Rock.

William Gaines developed his skill as a gardener and was in demand in the city. He was employed another pioneer Amos Harlow and helped to landscape Park Cemetery where he is buried following services at the Methodist church where the family was members.

His descendants have fond memories of him as a kind and population individual. He would carry a bag of candy in one pocket and pennies in the other, which he would hand out to neighborhood children.

Charles Gaines (1867-1917) the son of William and Mary remained in Marquette and worked as a barber and then a drayman. His ten children attended nearby Fisher school. In 1914 he ran for City Commission but was defeated by the incumbent. After his death in 1917, Mary moved her family to Chicago seeking expanded economic opportunity. Descendants occasionally return to Marquette for family reunions.

1900-1930

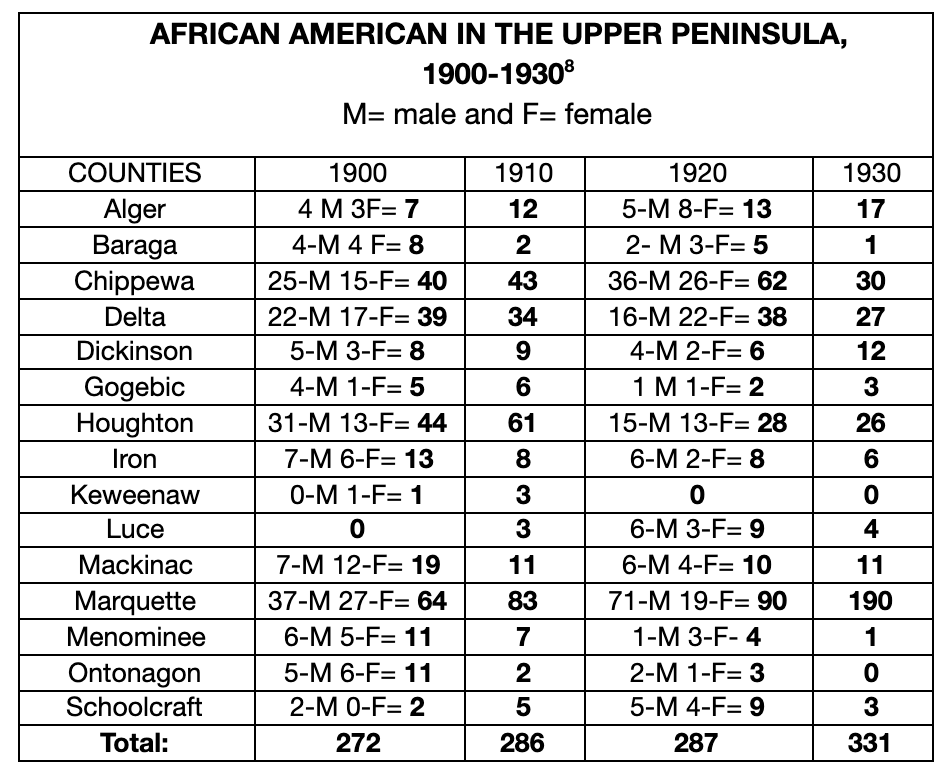

As seen below the African American population in the UP averaged 294 people between 1900 and 1930. During these years there was no economic opportunity to attract them to the region from large cities.

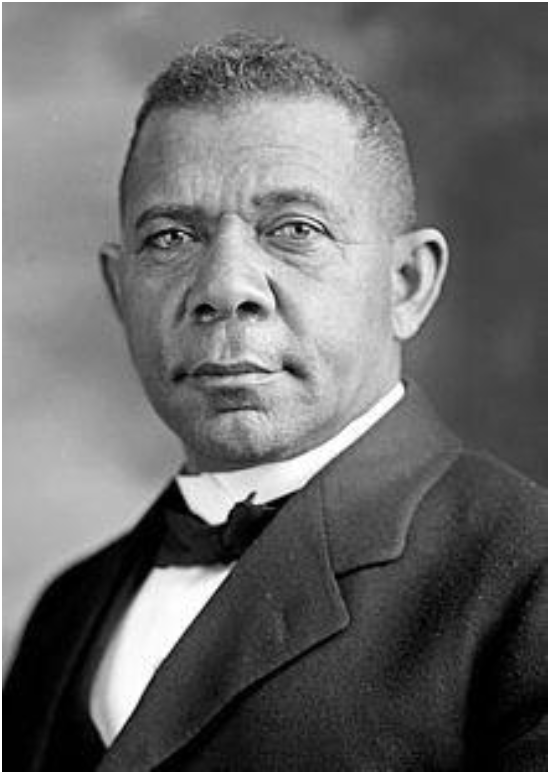

Booker T. Washington 1856-1915) educator, orator, author, adviser to multiple U.S. president, the dominant leader of the African American community, and founder of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama was invited by President James Kaye of Northern States Normal School (now Northern Michigan University) to come to Marquette. Probably, the main reason why Kaye invited him was the fact that Kaye grew up in the United Kingdom and his father John B. Kaye had been deeply involved in the anti-slavery controversy, which caused him to emigrate. Washington was scheduled to deliver a lecture on campus in the summer of 1907. Unfortunately he had to cancel the trip due to a busy schedule at Tuskegee Institute.

James Albert Rickman, Sr. was born in Canada in March 1868 and his parents were from Tennessee and Ohio. He immigrated to the United States in 1886. James and Jessie were married in Marquette in 1896. He was a successful barber with his own shop and the family of four children lived on the East Side at 328 Ohio and then 518 High Streets. His daughter, Blanche attended Northern State Normal School and became a teacher in the UP. His son James Jr. was active in school life and football in high school and college and graduated in manual arts. This is an example of a typical African American who migrated to the UP and his family made it their home until old age sent them to Chicago.

In the 1920s thousands of African American left the South during the “Great Migration” to escape peonage, share cropping, tenant farming and violence and settled in urban centers like Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit. Brown-Mitcheson, a lumber company in Marinette, Wisconsin recruited people through the black newspaper, Chicago Defender. The recruits would cut pulp wood and then settle on the cleared land in payment for the pulp wood.

A group of thirty-two African American men, women and children from Chicago traveled north in a three car caravan to Iron County in 1926. This small group planned to cut the forest trees, sell the wood and farm on the cleared land. They arrived and got organized and planned to call their small village, Elmwood. They dreamed of developing a rural life away from the frenetic experience of Chicago.

As long as the homesteaders kept to their property the local white population “tolerated the small community.” Then when the work was done the Wisconsin Lumber Company credited their work directly against the land purchase and as a result farmers and no money to invest in arable farming. They struggled through the winter, were starving and unable to receive assistance to continue farming in the spring. However they persisted. They farmed, cut and sold Christmas trees. In order to survive they fished the Paint River, poached and made moonshine. It should be remembered that in Iron County some members of the sheriff’s office were members of the KKK and deliberately led raids against moonshiners, who now were not only violating National Prohibition laws but were black. This was an ideal situation for the KKK and they seemed to act on it.

After encounters with the sheriff who arrested the men on a variety of charges they were threatened with jail or a return to Chicago and out of Iron County. The last of the colony left by 1930. As Dr. Valerie Bradley-Holliday has concluded, “Elmwood is a snapshot of the systematic dehumanization of people through the use of legal justice system.” This is a problem that continues directly face African American throughout the United States.

Asby Wood was on the Michigamme baseball team around 1930 so how did he get there? He was a chef on the railroad and probably boarded at Champion. In the summer he played local baseball and promote the game with local kids. In the winter he promoted winter sports and ski jumping. Later he opened a restaurant in Marquette.

During the Depression of the 1930s there were Civilian Conservation Corps camps across the UP. For instance at Camp Norrie #3601 Al Fehler boxed for local recreation and fought his way to the Golden Gloves Tournament in Chicago. Sammy Davenport stationed at Escanaba River Camp neat Gwinn developed his skill as a boxer. Earl March, whose family had settled in Munising much earlier was hired by the government to train 15-20 kids how to box two days a week.

World and Cold Wars

A world war and the Cold War brought the major influx of African Americans into the Upper Peninsula. As early as 1939 when Canada entered World War II there was a concern that canals at Sault Ste. Marie could come under attack from Nazi Germany and the movement of iron ore and copper halted, a major problem for national defense production. As a result every branch of the military number of over 10,000 men and women were assigned to defend the canal until after D-Day June 6, 1944 when there was a gradual removal of troops.

In the spring of 1942, the 100th Coastal Artillery, an all African American unit was stationed at Fort Brady. This brought a large number of Black troops into Sault Ste. Marie where housing was at a premium and strong prejudice developed. Female dates for the Black troops were bused up from Detroit for weekend dances. Finally, in March 1943 the Black troops were reassigned to Boston due to the rampant racism at the Soo.

The two Air Force Bases in the UP: Kincheloe 20 miles south of the Soo and K.I. Sawyer, 15 miles south of Marquette brought a large African American population to the area. Kincheloe was established during World War II as a refueling stop for planes flying to Alaska and for canal defense. Then it was closed for a number of years after the war but fully activated in 1963. By 1970 it had a population of about 10,000 of which 9,500 lived in Chippewa County and hundreds of the service personnel were African American. The base closed in 1970. K.I. Sawyer opened in 1955 and it had a large Black population until it closed in 1995. Many African Americans enjoyed the locations of both bases although isolated, they were in the North Woods where hunting, fishing and a variety of outdoor activities were readily available in summer and winter. At both locations there were educational opportunities at Northern Michigan University and Lake Superior State University. In both cases the African American population added to the culture of the institutions. A number of African Americans retired in Marquette and Chippewa counties.

African Americans at Northern Michigan University

In the years prior to the 1950s there were a few black students attending Northern.

James “Jack” Rickman was born in Marquette on May 14, 1902. His father James Sr. was a barber and they lived on the East Side of the city. James was active in high school life and played football. When he graduated he attended Northern State Normal School and majored in manual science. He was active in the local fraternity, Sons of Thor where he served as secretary to the active club in 1923 and played football. Upon graduation he taught on Neebish Island in the St. Mary’s River for a time before moving to Gary, Indiana where he taught for the rest of his life. He died on May 24, 1980. Another early student and athlete was Al Washington, who highlighted Men’s Track and Field. On January 14, 1961, at Central Michigan University, Washington ran the indoor 60-yard dash in 6.0 seconds, which was at that time the world record.

With the coming of President Edgar Harden in 1965, enrollment patterns changed. Northern’s Right-to-Try Program attracted African Americans students; K.I. Sawyer Air Force Base had a Black population that was drawn to the University; African American athletes came to Northern due to expanded football and basketball programs; and finally, the Job Corps, which opened on campus in 1966, attracted Black students. Although exact figures are not available, there were approximately one hundred Black students on campus in 1961. This figure grew to around three hundred in 1969-1970.

At that time there were a number of incidents involving Black students that many people, especially Black, saw as racially motivated on the part of the University administration. In the fall of 1969, Charles Griffis was suspended for violating a housing rule. This followed by protests, a sit-in, acquittal, acquisitions and a general erosion of race relations. As a result, many Black students left campus in the spring of 1970 and the general Black population never returned to its highwater mark. By 1978, when records had to be kept due to federal mandate, there were 216 Black students on campus. Between 1981 and 1990 there was an average of 211 Black students on campus.

During this period, Black students had their own fraternities and sororities. In April 1971, Ozel Brazil ran for president of NMU’s student body as an Independent and received 578 out of the 1,350 votes. He was the first African American elected as president of the Associate Students of NMU.

Black Student Services was an African American organization started around 1970 and developed many branches. One of the most active branches was the Black Student Union as was the Social Cultural Committee. Together they started several celebrations and programs that are continued to the present.

A number of important Black cultural developments took place at this time. Black History Month was started around 1980 brought to campus by the Black Student Union, the Social/Cultural Committee and Alpha Delta. It celebrated African American culture, accomplishments and history by bringing speakers, music, meals and cultural events to campus. It has developed into a larger event. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day began in January 1986 as a one-day event and by 1993 had turned into a week-long event and the federal holiday is celebrated on campus promoting community involvement. Beginning in December 1993 the celebration of Kwanza was celebrated for a number of years but has declined because it takes place during the holiday break and classes do not begin until mid-January.

Dr. Arthur Walker was the first director of Black Student Services on campus. Beginning in 1974 after this death, the Dr. Arthur Walker Memorial Scholarship Fund Fashion Show was started and held in cooperation with local businesses to raise scholarship funds. It seems that it has gone dormant in recent years.

Around 1990 Black Student Services was combined with the Native American Student Services office under the Dean of Students to form the Multicultural Affairs Office. This office has undergone changes and in 1999 it was called Diversity Student Services. The role of the Black Student Union has now fallen to organizations such as Ebony Excellence, Sisters of X and Essence which have gone dormant.

Other Black student organizations on campus and surrounding communities in Marquette and the former K.I. Sawyer Air Force Base there were many organizations that were active through the 1990s. Much of this fell apart with the closing of the Base in 1995 and the loss of its African American population that interacted with the Black population on campus.

Over the years ten prominent African Americans have received honorary degrees from Northern:

Richard H. Austin (1913-2001) – first African American to be elected to statewide position as Michigan Secretary of State (1971-1995) . (Degree awarded: 12/1989)

John Hope Franklin (1915-2009) – outstanding and famed American historian.

Patricia R. Harris (1924-1985) – first African American to reach ambassadorial rank (Ambassador to Luxembourg); first African American to be a member of a presidential cabinet: 1977-1979 Secretary of Housing and Urban Development and then Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare. (Degree awarded: 08/1973).

Clara S. Jones (1913-2012) – first African American to head a major public library: Detroit Public Library and president of the American Library Association. (Degree awarded: 05/1978).

Ward Harper McCree (1920-1987) – judge of the US District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan; US Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit. (Degree awarded: 05/1985).

Gordon R. Parks (1912-2006) – American photographer, musician, writer and film director; documentary photographer from the 1940s through the 1970s. (Degree awarded: 05/1997)

Willis Franklin Ward (1913-1983) – track, field and football at the University of Michigan. In track and field he was the third All American and 8 time Big Ten champion. Lawyer;

Michigan Public Service Commission (1966-1973) and chair 1969-1973; probate judge of Wayne County. (Degree awarded: 01/1970).

Myron H. Wahls (1935-1998) – circuit court judge and declared “Michigan’s Most Outstanding Judge; Detroit piano jazz legend. (Date warded: 04/1996)

Clifton R. Wharton, Jr. (1926- ) – president of Michigan State University (1970-1978); chancellor of the 64-campus State University of New York and then chairman of the Rockefeller Foundation; deputy secretary of state in 1993. (Degree awarded: 12/1975).

Roger Wilkins (1932-2017) – Civil Rights champion in government and journalist who won a Pulitzer prize. (Degree awarded: 12/1994).

Prejudice

Over the decades African Americans have had to deal with prejudice. In the nineteenth century African American women were at times labeled in newspapers as “wenches” and there was an incident of mistreatment in a saloon in the 1880s. In 1913 when an African American family settled near Round Lake in the eastern Upper Peninsula the Newberry News described their presence as “. . . distasteful to the residents owning property situated on Round Lake.” As we have seen a more complete story of racial prejudice took place in Iron County in the late 1920s.

An American form of racist entertainment developed in the early nineteenth century was known as the minstrel show, that became popular throughout the United States. The show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, and musical performances that depicted African Americans but mostly performed by white people in make-up or blackface for the purpose of playing the role of Black people. These shows were presented in towns and cities across the UP but service and fraternal organizations, community groups and universities. The last one at Northern was presented by a fraternity in 1958.

During the decade of the 1920s the Ku Klux Klan was active throughout the Upper Peninsula. Since there were few African American to direct their un-American activity they supported National Prohibition. They went after immigrants like Italians, Slovenians Germans and others who made wine, beer and distilled hard liquor in the woods. Fiery crosses buried on hill tops and dance hall owners were threatened as were Catholic churches. One story told was that at this time the KKK had a chapter in the Marquette Branch Prison in Marquette where many of the inmates were Black. It is uncertain what they planned to do.

A brief search of property records in the Marquette County Courthouse provide evidence of what people talked about in the form of a “protective covenant.” At this time there were 269 Black males and four female in Marquette. In the late 1940s the first subdivision development, Shiras Hills, took place in Marquette. In July of that year a protective covenant was circulated by the developer which stated: “No part nor the whole of any lot shall ever be occupied or used for any purpose by any person other than a member of the Caucasian race . . . .” This not only prohibited Blacks but also Asians Americans and Native Americans. However African Americans could hired as servants and occupy rooms in the household. This covenant was finally removed in the 1960s as the Civil Rights movement brought an end to such covenants even on the northern frontier. In the early 1960s Ironwood was a “sundown town” meaning that African Americans had to be out of town by sundown. In 1960 out of a population of 10,265 there was only one Black male living in the city. However, Black crews on the Chicago & Northwestern Railway who wanted to step off the train and have a cigarette, were cautioned to remain onboard and avoid local harassment from Ironwood police. This story was posted to the web, 2005 by a former resident:

My father worked for the Chicago & Northwest RR and told me that as recently as the early 1960s anyone black on train crews would be told they couldn’t stay overnight in Ironwood. The porters on the passenger trains experienced enough harassment from local law enforcement that they wouldn’t step on to the depot platform while the train was in the station… I took the train often enough back then to notice and when I asked my dad why the porter never got off the train there he explained that Ironwood was a sun down town (and that’s the phrase he used) where blacks were not allowed to spend the night or, indeed, even be on the depot platform passing through once the sun went down.

It should be added that in the 1990s when the Ku Klux Klan from Wisconsin tried to get established in Ironwood they were met public outrage and condemnation and were literally driven from town.

Beginnings of the 21st Century

The African American population in the Upper Peninsula remains characteristically small. Some of the retirees from the Air Force continue to live in the UP. The academic institutions: Lake Superior State University, Michigan Tech, and Northern Michigan University attract African American students and faculty members. However the numbers are small at Northern where in 2021 out of over 7,000 students there are only about 160 African American students. The first African American professor hired at Northern was Dr. David W.D. Dickson who was department head of the English Department from 1964 to 1966. In the following year he became vice president for Academic Affairs. There are a number of African American physicians and other professionals in the UP who add their knowledge and expertise to the world of the UP. Two African American professionals will be highlighted. Dr. Carter A. Wilson is professor and head of the Department of Political Science at NMU. His specialties include: Public, Civil Right and Economic Policy and Public Administration. In 2015 be published a book dealing with Civil Rights, Metaracism: Explaining the Racial Inequality. Dr. Valerie Bradley-Holliday is a licensed Clinical Social Worker with a doctoral degree in social psychology. She also has a special interest in African American heritage in the Upper Peninsula. Her two publications are: Places to be Blessed and Northern Roots: Africans Descended Pioneers in the UP of Michigan.

Dr. Valerie Bradley-Holliday

So we have come to the end of the quest. This has been the first extensive overview of a topic that has been sadly overlooked in the past. It is obvious that the work of the author and others Dr. Bradley-Holliday must continue so that the complete story is eventually told and made available to the public.

Very interesting. Was completely unaware of this information. Thank you for taking the time and energy to put this article together and sharing.

I am a seventh generation Michigander who enjoys reading and learning about the State I reside in. My mother was a member of Daughters of the American Revolution. Thank you! Charles C. Hagen MSA Central Michigan University.

Re: Covenants: The Shiras Hills Covenant also barred “non-Christians” from purchasing homes.

I read both stories, and thought they were excellent. Thankyou

The two articles surely have added immensely to the scarce knowledge about Afro-American descendants in the UP and the Upper Lakes region. I hope they will find a wider audience somewhere, and that the second one will be edited and the two released as a single piece or broken down as a series and published in the Mining Journal next February. The dates that degrees were awarded in the second article should be vetted, they don’t seem logical.

Thank you for publishing this and thanks to the authors for their excellent work in assembling this history!

Lived in Marquette, 1959-1963. One weekend night in 1962 or 1963, We were “out on the town”! We decided to go to a bar that was located in the basement of a local hotel. As we descended down the steps we were confronted by a velvet rope across the entrance. We noticed a “Reserved” sign on every table. I commented,”Oops! We can’t stay here! All the tables are reserved!” A man quickly approached from the rear and said, “Just for you, sir!” Never forgot this. . . . .

My grandfather was an airman. He refueled in the U.P. headed to base in Fairbanks AK. I have roots/family in the U.P. but I dont visit. They hate us there now just like they hated my ancestors there then.

Today we remember Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965. I am reminded of a day 50 years ago during the spring semester of 1972 when I was the only white NMU student in Dr. O’Dell’s Afro-Americans in American History class. It was new class at NMU…a new subject at a critical time in our nation’s history. There were 17 black students in the class, including our NMU student body president Ozel Brazil from Detroit. I had voted for him the previous spring as did enough NMU students to vote him in as the very first black student to ever serve as our leader. Anyway, when the class started, I was a little bit ill at ease, being the only white student in the class, a kid from the UP community of Negaunee at that time. But sitting next to me that day of remembrance, was Ozel, a hero of mine because of his courage, friendliness, and leadership skills. Anyway, our professor kept referring to black people during his opening lecture as “Negroes.” It didn’t take long for Ozel to raise his hand so that he could speak. O’Dell called on him. Ozel stood up and spoke, “We want to be called Black people now. Why do you keep on referring to us as “Negroes? We find it derogatory.” Our prof was silent for a moment, but then came back with his 1972 answer. “Because you belong to the “Negroid” race, and thus others refer to you and other Afro-Americans as being “Negro.” Without batting an eyelash, Ozel very respectfully, but with a smile on his face, responded back, “That may be so, Dr. O’dell, but I don’t go around calling you a Caucasoid!” There was complete silence in the classroom. I turned and stared at our prof. He just stared back for a moment at all of the nodding heads. That was it. After that, Dr. O’Dell only referred to Black people as Black or as Afro-American, never ever again using word “Negro.” This was one of my greatest NMU memories. 50 years have now passed and I am still inspired by Ozel Brazil standing up on that day and demanding respect.

I have just reviewed the article and it’s commentary. I was informed, interested, and very grateful to the contributors. After the World has experienced COVID-19, uncontrollable wildfires, severe storm surges, unquantifiable death tolls, changed societal norms, and advanced 21st century views in science, medicine, technology. Why are we still focused on a person’s skin color and not the content of character, cultural contribution, and diverse relationships that promote solutions to cure the World to become healthier human inhabitants. Can’t we learn from our past and focus on our combined present and positive future to be better citizens to each other. We need to change now, before it’s too late!!! Food for thought….. What is our changing World showing Us?