Boom and Bust: Calumet and Keweenaw National Historical Park 30 Years On

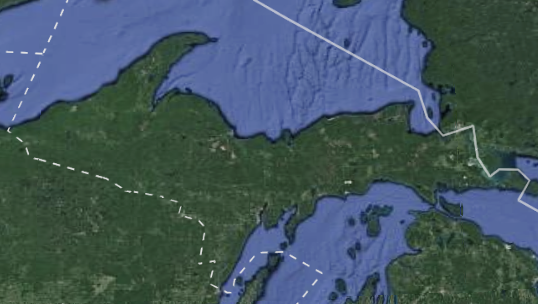

Many communities throughout the Upper Peninsula have developed their sense of place from the mining industry. On the Keweenaw Peninsula, copper mining dominated the local economy for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. When mines inevitably shut down, the affected communities must look elsewhere for economic development opportunities and a new sense of cultural identity. Keweenaw National Historical Park (KNHP) centered on Calumet was established in 1992, 24 years after the Calumet and Hecla mining company closed in 1968.

The loss of jobs forced many workers to leave the region, leading Calumet and the surrounding region’s economy to decline. After much deliberation about the community’s future economic development, it was decided that tourism combined with historic preservation offered a way forward and local leaders began working with Michigan’s congressional delegation to establish a National Park. The park serves as a physical manifestation of a mining community’s efforts to find its place in a post-industrial world. This article considers KNHP’s impact on the Calumet area’s economic development. First, a brief historical overview of the Park’s development is provided.

Calumet, located in “Copper Country,” has an extensive history of copper mining. Long before European colonization, the region was home to indigenous copper mining with Western extraction beginning in the mid-nineteenth century. By this time, 95% of the copper used around the United States came from the Keweenaw.

Keweenaw National Historical Park represents an effort at preserving the mining and labor history of this rural region; at its heart is the village of Calumet (2020 population: 621), with a historic district containing many buildings dating back to the early twentieth century. The politics of the time helped shape KNHP’s creation. Federal budget cuts, the difficulty of federal land acquisition, mass private-land ownership, and relatively large local populations resulted in the park adopting a decentralized management model.

The National Park Service (NPS) refers to KNHP as a ‘partnership park,’ meaning a park with an intertwined public-private model where federal, state, and local ownership is in place. This was a key factor in its approval by the Bush administration. The initial idea made by locals was for Calumet’s history to be preserved as a National Park, a process which started with Calumet’s Downtown Development Authority and eventually involved faculty from Michigan Technological University, meetings with NPS officials and Congressmen. Once local media got ahold of the project, it gained popularity from residents eager for economic growth with local business people believing a park would help the economy.

Leadership at the Park Service was less enthusiastic about the park’s creation with the director concerned that the park failed to meet a “national significance” standard at a time of budget constraints and advised Congress that full ownership of the park would be too expensive. At the same time, other Keweenaw residents suggested that the park’s boundaries be widened to include the Quincy Mining District since Quincy still had an open mine shaft and Calumet did not. Within Congress, the park’s creation was opposed by those who regarded it as an economic development project.

The end result was a public-private partnership for the Keweenaw region which made it easier for Congress to pass the bill creating the historical park. After President Bush signed the legislation establishing KNHP local residents were optimistic that an expected influx of outside money and tourists would boost the economy. The remainder of the article uses Census and Bureau of Labor Statistics data to assess whether local residents’ economic expectations were met.

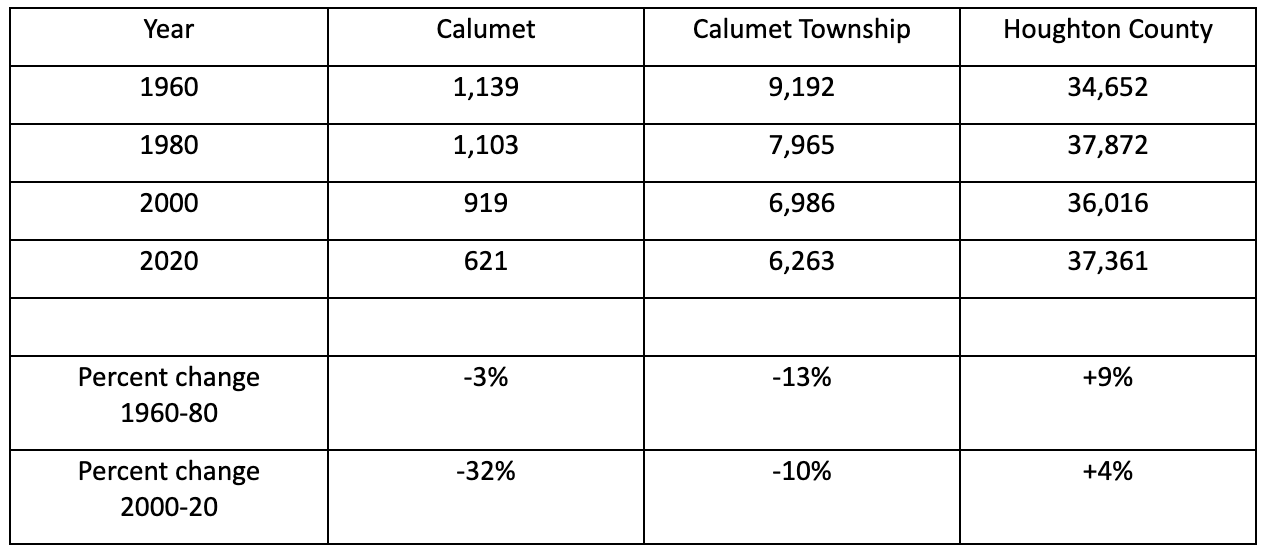

After the Calumet and Hecla Company closed operations in 1968, it was inevitable that the area’s population would decline (Table 1). Between 1960 and 2020 Calumet Charter Township’s population dropped by nearly 3,000 persons, while the equivalent figure for the village is just over 500. In contrast, Houghton County gained population. More significantly, the village of Calumet’s population experienced its greatest population loss between 2000 and 2020, a few years after KNHP was created.

Table 1: Population of Calumet, and Calumet Charter Township 1960-2020

Calumet Township includes numerous unincorporated communities along with the villages of Calumet and Laurium.

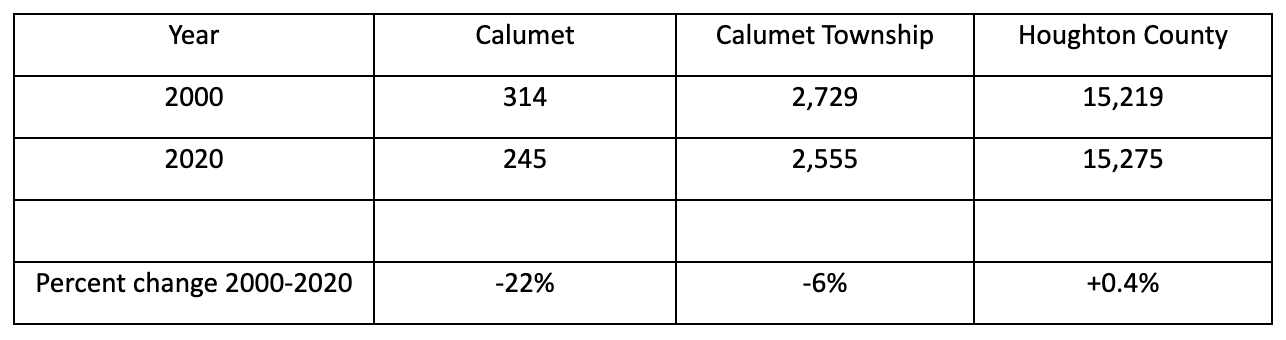

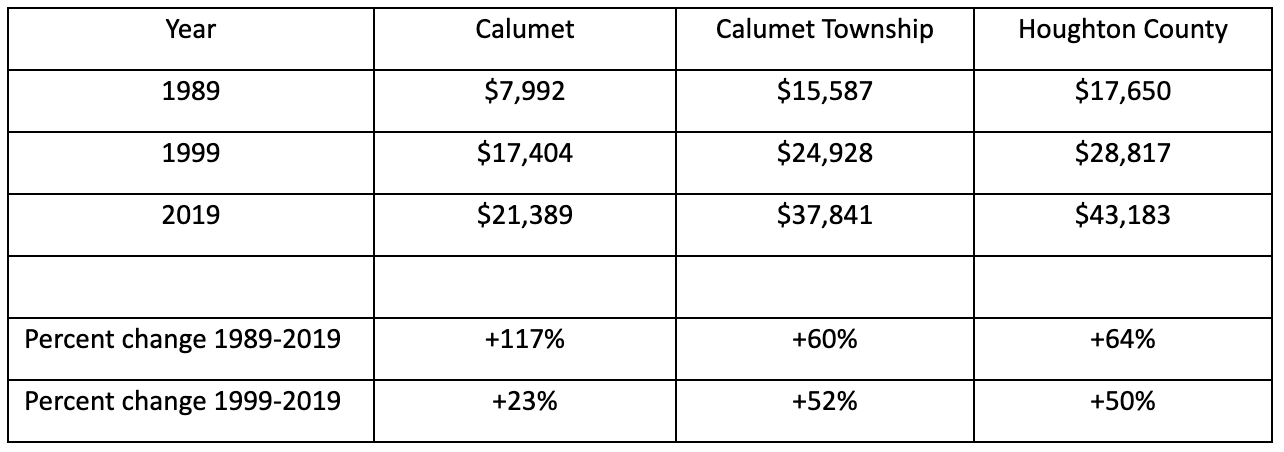

These population losses led to declines in the number of employed persons in Calumet and the Township (Table 2), while Houghton County experienced a modest gain in employment over the same period. Economic data indicate that despite gains in household income in Calumet and the Township since 1989 it remains below the comparable figure for Houghton County (Table 3). Calumet’s median household income was 45 percent of the County’s in 1989; thirty years later it was 49 percent. Finally, Calumet’s poverty rate of 30.6% in 2019, is much higher than the comparable figure of 20.2% for the County.

Table 2: Employed Persons: Calumet, Calumet Charter Township, and Houghton County 2000-2020

Table 3: Median Household Income: Calumet, Calumet Charter Township, and Houghton County 1999-2019

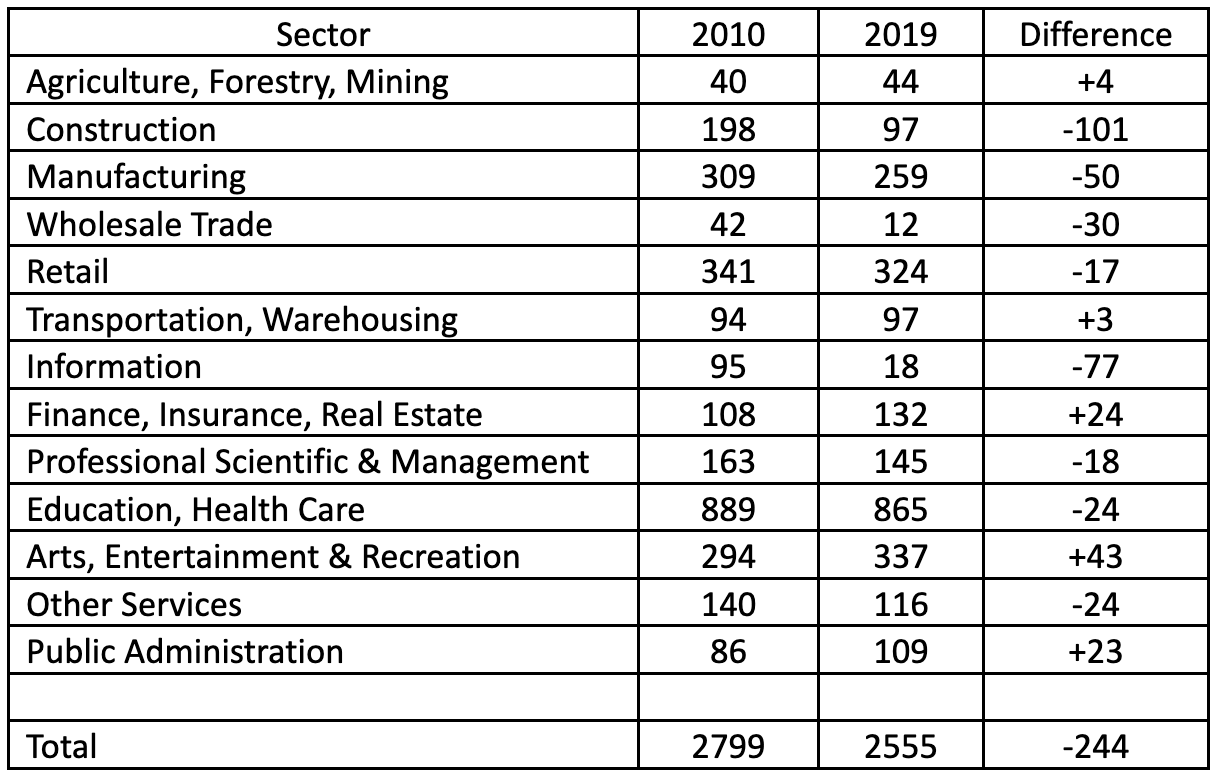

Calumet and the Township’s economic performance can, in part, be explained by shifts in its employment structure. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data (Table 4), since 2010 the area has lost relatively high paying jobs such as construction (2019 County average annual pay of $45,478) and manufacturing (2019 County average annual pay of $39,873) and gained low paying jobs in entertainment and hospitality (2019 County average annual pay of $13,753).

Table 4: Calumet Township Change in Employment Structure, 2010-2019

Indeed by 2019, as overall employment has dropped, tourism-related jobs have increased to become the second-largest sector of the Township’s employment structure, after Education and Health Care. In addition to being low-paying, tourism jobs tend to be part-time, and seasonal. Seasonality is a particular issue for KNHP, the NPS’s Calumet Visitor Center is only open on Fridays and Saturdays for 10 hours during the winter months, while the Keweenaw Heritage Center is only open during the summer months. Prior to the pandemic, annual park visitation in 2018 and 2019 averaged about 20,500, according to National Park Service statistics, with 96 percent of visits occurring between May and October.

Over thirty years ago Calumet and Copper Country residents looked to heritage tourism to boost their economy. Meeting such an expectation would always be difficult given tourism’s seasonality and that many of its related jobs are part-time and low paying. Keweenaw National Historic Park is well worth a visit for a reminder of mining’s role in the development of the Keweenaw but its ability to drive the local economy is limited given the nature of tourism.

Sources:

Liesch, Matthew. Creating Keweenaw: Parkmaking as response to post-mining economic decline. The Extractive Industries and Society, 3 (2016): 527-538.

Liesch, Matthew. Spatial boundaries and industrial landscapes at Keweenaw National Historical Park. The Extractive Industries and Society, 1 (2014): 303-311.