Alcohol Drinking in the Upper Peninsula

At various times you hear about the role of alcoholic beverages in the history of the Upper Peninsula. This has been a problem for many people over the years and there were numerous attempts to try to control the production and sale of these spiritous beverages.

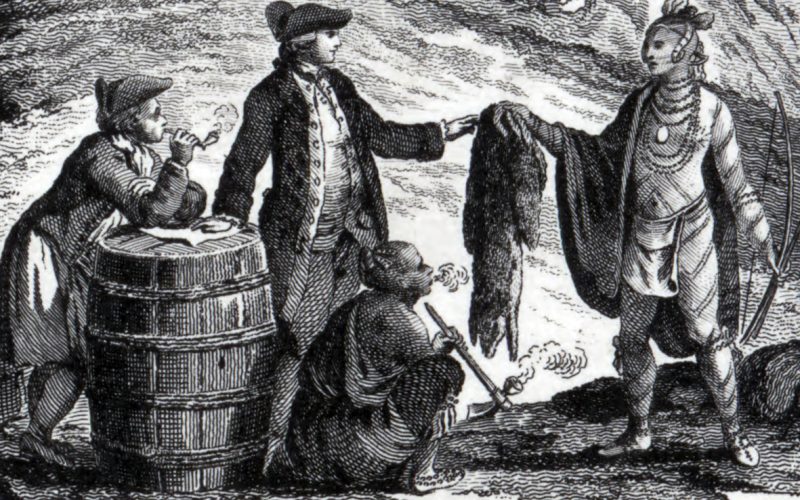

The earliest alcoholic addiction in the Upper Peninsula goes back to the seventeenth century. The arrival of the Europeans brought with it a flood of alcoholic beverages especially brandy and rum by the French and British respectively. When the French arrived in the mid-seventeenth century they introduced the fur trade and furs were traded for brandy. The Jesuit missionaries saw the deadly effects of alcohol and protested its trade. Paul La Jeune, SJ was one of the first to observe the results of brandy trade in 1632 writing of the destruction and depopulation of the Native People. Drunken Indians “had an irrefutable excuse for whatever violence and destruction they committed.” During a spree Indian villages became “veritable images of hell” with cabins burned, ears and noses torn from faces and opponents and friends killed. When this occurred Indians fled to the woods and missionaries and traders stayed in their forts and homes awaiting the end. In reality this was not merely drunkenness but alcoholism which set in and debauched the people the missionaries sought to evangelize.

Over the years various Jesuits sought to intervene and hopefully remove the Native Americans from the occasion of getting drunk on alcohol with mixed results. At St. Ignace, Étienne Carheil, SJ was disgusted with what he encountered and reported such in late August 1702. He attacked the “infamous and baleful trade in brandy” that led to acts of brutality, violence, contempt and insult as he put it. This trade would be forbidden by the king Louis XIV if he were aware of the results. Writing near-twentieth century terms, Carheil pointed out that brandy led to prostitution, gambling, and drove the Indians from the missionaries and their work. However, the fur traders had a show-down with the missionaries and asked them if “they wanted brandy drunk Catholic Indians or rum soaked Protestant Indians.” From Michilimackinac to Detroit, the fur traders despised and hated Carheil and any other Jesuit who dared to speak against the trade with brandy.

Some Native Americans were horrified at what they saw among their people who were turned into “monsters” poisoned by brandy, which “took away the senses and caused untimely deaths.” Besides their physical destruction these alcoholic Indians were financially ruined and saw their families fall apart.

By the time of the end of the French and Indian War in 1761 nothing had been done under the French to end the brandy trade and now the English traders entered the Upper Peninsula with their kegs of rum. The English military sought to police the fur trade and Indian affairs in order to avoid conflicts. Captain Donald Campbell in May 1761 called for the end of the rum trade because of its destructive effects on many of the Native People. Soon after, General Jeffery Amherst, British commander in North America called for the total prohibition of rum to the Native People throughout British North America because of its destructive and detrimental effects on them. By 1773 some Indians came forth and pointed out that despite these prohibitions more young Indians died to alcohol abuse than were killed in battle. There were unscrupulous traders, who knowing the destructiveness of rum continued to deliver rum.

The British soldiers at Forts Michilimackinac and Mackinac on the island after 1781 had their own encounters with rum. In these isolated posts alcohol was their chief form of amusement and there were all-night parties where vast quantities of fortified “wine” punch was consumed. Here too some of the soldiers became violent and belligerent and destroyed property, raped wives and beat husbands when they tried to intervene.

Despite the official warnings, rum continued to enter the western frontier. In 1781, there were 3,084 gallons stored at Fort Mackinac. If rum became too expensive the military substituted cheaper porter or a good wholesome beer.

Locally, alcoholic beverages were easily produced. Spruce beer was a light beer easily produced and known to keep scurvy at bay. It was filled with vitamin C. Fruit, wild or domestic and potatoes were easily fermented and distilled. Prior to the War of 1812 the first distillery in the UP located on Mackinac Island was in operation. The drinking habit was met.

Alcohol abuse was a major problem for the English and after 1796 among the American soldiers stationed at Fort Mackinac. To attempt to control alcoholism, drunkenness was considered a major offense for being court-marshalled. In 1889 the commander at the fort opened a beer bar in the fort an attempt to keep the men from venturing into town and drinking hard liquor.

Although Indians were debauched and degraded by firewater, congressional and executive regulations and orders did little to stop the flow of hard liquor into the UP. In 1832 some 8,776 gallons of liquor landed at Mackinac Island. The head of the American Fur Company, John Jacob Astor tried to convince the Native Americans that they were more productive and thus wealthier without liquor, but his arguments fell on deaf-ears. The old story arose – if AFC did not provide liquor the Indians would get it from the British. When traders returned from their western treks they celebrated at Mackinac, where drunkenness led to brawling and frequent murders were part of life. A New York physician, Dr. Chandler Gilman in the summer of 1835 enroute to visit the Pictured Rocks near Munising, stopped at Sault Ste. Marie. He was appalled at the alcoholism among the Native People who he described as “slaves to rum.”

The Catholic and Protestant missionaries, arriving in the early nineteenth century were quickly scandalized by the effects of alcohol. In October 1828, Baptist missionary, Abel Bingham settled at Sault Ste. Marie. Liquor was plentiful and intemperance was a common vice among the soldiers at Fort Brady, civilians and the Native People. As a result, he established the St. Mary’s Temperance Society in May 1830 and most officers and soldiers, as well as fur traders became members. Even the fort sutler, John Hulbert, who had been selling twenty pints of whiskey a day took the pledge not to drink and lost revenue. Methodist missionaries like Reverend John Pitzel worked unceasingly to end the liquor trade and Native consumption of spirits. The Catholic missionary, Rev. Frederic Baraga also promoted temperance had Catholic laymen and Native Americans take the pledge not to drink. He wrote in his journal that he disliked July 4th because the celebrating led to drunkenness which resulted in fighting and violence among the miners. From Beaver Island, the Mormon leader, James Strang highlighted the Irish fishermen operating out of Mackinac Island who traded watered-down and adulterated with tobacco and chili pepper whiskey to the Native Americans.

Philetus Church who settled on Sugar Island in the St. Mary’s River below Sault Ste. Marie in the 1850s. He successfully provided work for the local Native population and kept alcohol away from their communities. However, people like Church were few and far between.

In the mid-1840s copper and iron were discovered and the deposits developed and a new era of drinking began With the developing of the mining and timber industries alcohol because a recreational habit especially with the miners. As historian Larry Lankton has written, on the mining frontier, “imbibing alcohol became common pace in conjunction with sports and games, holidays, elections, and long winters infected with cabin fever.” From the earliest days liquor literally poured into the UP with ships arriving throughout the summer months loaded with vast quantities of whiskey, gin and rum. Saloons dominated towns and cities throughout the region. Drinking hard spirits and beer was a common practice for miners returning from work on their way home. This addiction of some led to spending their pay check at the saloon much to detriment of their wives and children. Violence social disorder was part of the drunkenness. It was obvious that alcoholism was a social problem in the Upper Peninsula and throughout the United States.

As result the incoming white settlers sought to re-introduce and promote temperance. In 1847 The Lake Superior Temperance House was opened by John B. Martell at Sault Ste. Marie. It was “conducted on principles that characterize the most fashionable Temperance Hotels of the East.” The vistas from the hotel were enticing, the food great, and families were encourage to stay. In May 1852 James K. Paul in May 1852 opened the three-story Temperance Hotel at Ontonagon, but down the street Corbis & Shepherd were putting an addition to their popular and busy tavern.

To promote an end to addiction, an ad appeared in the Lake Superior News in 1852 promoting “an excellent little temperance story “ Albert Loveland; Or the Maine Law Is the Inebriate’s Hope authored by Electa M. Sheldon. The book reviewer concluded:

It is an able advocate of the Maine Law and illustrates in bright colors the blessings that such a law gives to the individual and the community, and the friends of the cause could not send a better advocate than this to the foresides of our growing communities.

Despite these meager attempts to curb alcoholism, the trade flourished throughout the nineteenth century. Saloons thrived and spread through communities. In 1877 Calumet with a population of 7,000 supported 24 saloons, meaning there was one saloon for every 166 residents of all ages. Republic’s thousand residents were served by eight saloons. By 1903 Marquette, “the Queen City of the North” with a population of 11,000 had 43 saloons downtown along Washington, South 3rd, Baraga and South Front Streets. Another seven were scattered on the margins of town. In 1916 on the eve of state prohibition, Escanaba with a population of 18,000 planned to pass an ordinance to limit the number of saloons to forty! At this time saloons readily served shots of whiskey and mugs of beer, which were enhanced with salty food at the end of the bar.

The Methodist, Presbyterian and Baptist churches took strong anti-alcohol positions. The Catholic church was less vocal in its position but it was there. Immigrant groups like the Cornish in their Methodist churches and the Finns and Finn Swedes established temperance societies throughout out the Upper Peninsula. In 1874 the first constitution of the national Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (W.C.T.U.) stated as it object: “The education of the young; the formation of a better public sentiment; the reformation of the drinking classes; the transformation by the power of divine grace of those who are enslaved by alcohol; and the removal of the dram-shops from our streets by law.” The groups developed chapters throughout the UP and were visited by speakers promoting their objectives. The work of the WCTU, the Anti-Saloon League and politicians led to Michigan voters in 1916 passing a prohibition law which went into effect on May 1, 1918. National Prohibition went into effect in January 1919. The wets from the start said that Prohibition would not work and the law would be violated. At this early date Midwesterners promoted the idea that if they wanted to know how to violate the law, merely ask a Michigander.

Bootlegging began immediately. Stills cropped up throughout the cities, towns and woods of the Upper Peninsula. Although the Michigan Constabulary, now known as the State Police, was on guard and broke up stills and speakeasies their job was not that simple. The locally distilled “white lightening” was poorly made and deadly. The illegal stills in the woods produced clear alcohol that was colored and flavor at times with chicken bouillon. As a result, those who could, obtained British-made scotch and gin delivered across Lake Superior by boat ($600 per trip) and airplanes or across the St. Mary’s River, poor guarded by the Coast Guard. Al Capone sent crews north from Chicago to obtain cases of liquor across Whitefish Bay. By the way, his favorite beverage was Canadian Club whiskey. Visitors to Mackinac Island could enjoy their liquor at the Grand Hotel where “nannies” delivered bottles in baby carriages or you could enjoy dancing, gambling and drinking in a well-guarded casino on the premises. At one point the guard was an older woman folding hotel laundry at the entrance, ready to alert the casino. So the demand for alcohol was rather easily met.

October 1929 brought the stock market crash and the Great Depression, which would lead to the end of Prohibition. There was a demand for jobs, which could be provided by breweries and distilleries opening. Taxes on liquor would bring in revenue to money-starved states and communities. A cold bottle of beer would be pleasant relaxation during these hard times. On April 10, 1933, Michigan was the first state to ratify the Twenty-First Amendment which ended Prohibition and by December 5 (Repeal Day) the great experiment came to an end.

Despite the collapse of probation in the state, there were some attempts in the late 1930s to reinstate prohibition. One argument was that in 1937, $264,000 was spent on liquor in the area of Sault Ste. Marie amounting to $1200 sold per day in hard liquor, while local churches never received any money close to these latter figures. In July 1939 the anti-liquor folk saw some hope for a return to prohibition in Governor L.D. Dickinson who had shown support for its return. He sought to employ his account of drinking parties at a recent National Conference of Governors as the springboard for a campaign to return prohibition to Michigan. The dream of some lingered into 1940 but nothing came of this preposterous idea.

Although, Prohibition ended, the state of Michigan carefully oversees the production, distribution and sale of alcohol through the Michigan Liquor Control Commission. It regulates the number of bars or cocktails lounges allowed in a community and the sale of liquor through its distribution centers sometimes referred to as “the liquor monopoly.” Michigan allows any city, village or township in which there is no retail liquor licensee to prohibit the retail sale of alcoholic liquor within its borders by passage of an ordinance. As of this writing Tuscola County is the only county in Michigan with a countywide ban on Sunday liquor retail sales. Patrons can enjoy liquor and mixed drinks at a bar or restaurant on Sundays, but can’t purchase and take home a bottle. Beer and wine sales are allowed after noon. Another little known state law is that liquor cannot be sold from 11:59 pm December 24 until noon December 25.

The first German brewery in the UP was opened in Sault Ste. Marie in the summer of 1850 by the German immigrants: Nickols Voelker (grandfather of author John Voelker), Joseph Clemens, and Nikolas Fritz. Before prohibition the UP had at least one brewery in every large community: in the Copper County (5), Marquette County (3), Escanaba (2), Menominee with its large German and Bohemian populations (3) and eastern UP (2) . With repeal a few reopened and then quickly closed overwhelmed by large national brewers. Only Bosch Brewing in the copper country survived doing its best to remain in business by modernizing equipment and space and presenting a new product, Sauna beer, but it too had to close in 1973. Since 1994 craft breweries and pubs have become popular with some nineteen in operation throughout the UP. They are no longer “dens of addiction” but serve as social centers usually serving only beer and some have added restaurants or food trucks in the vicinity. In recent years three distilleries have opened in the UP: Les Cheneaux Distiller, Cedarville; Cedar Naturals, Atlantic Mine, and The Honorable Distillery, Marquette.

Today, changing life styles and state ordinances have brought an obvious change in the city of Marquette and immediate vicinity with a 2021 population of 36,644, there were only six bars and fifteen restaurants selling alcoholic drinks or cocktails and not the fifty saloons of 120 years ago. The three brew pubs in the city are social centers for a few beers with no outbursts of drunken violence connected with them.

So as we come to the end of this tale we find that the Upper Peninsula has moved away from the widespread sale or trade of liquor to alcoholics and now the sale of liquor has become more of a restrained social event in many cases associated with food.

For additional reading on this subject see: Russell M. Magnaghi. Upper Peninsula Beer, A History of Brewing Above the Bridge and Prohibition in the Upper Peninsula, Booze & Bootleggers on the Border at your library, local book store or on-line.

Thanks Russ, another fine tale of Michigan history.

This was very interesting.

Interesting. Finnish ancestors settled in Herman and Hancock, MI in mines. Then my grandparents and a great-grandfather who lost part of an arm in a mining accident moved to Maine.

Alcoholism has created havoc in my family. Currently 5 generations that I’m aware of. Also my ex-spouses family.

Great article. Makes me wonder about the proliferation of pot shops in Marquette and across the UP. There are consequences to using this substance. “Tell Your Children, the Truth about Marijuana, Mental Illness and Violence author Alex Berenson makes a case for the destruction caused by this drug.

It’s also worth noting that marijuana has a multitude of benefits as well, so informing appropriately aged youth of the side affects is much more proper.

I remember driving to Ironwood on M28, and my mom would veto stopping in Newberry for lunch because Luce was a dry county in the early 50s.

Any one remember the last county to allow liquor sales as Luce?

Can’t wait to read the book and get the whole story.