Gender and Factory Work in the Upper Peninsula – Part Two

“Rural Voices” shares cultural, educational, economic and artistic views of people who have lived and thrived in the Upper Peninsula. Each of our authors in Rural Voices may be living here in the U.P. or living someplace around the globe, but the U.P. is an important part of who they are and what their beliefs and values are today. Rural Voices wants to share the voices of our neighbors and friends about life and experiences in the UP.

If you haven’t yet read Part One, you can do so here.

PART TWO

Now we turn our attention to the industrial development of the mining regions: the Marquette, Menominee and Gogebic Iron Ranges and the Copper Country.

The mines provided jobs for the men as seen at the largest employer: Calumet & Hecla Mining Company in Calumet, who in 1919 had nearly 6,000 men employed in its mines and mills. From the beginning, the goal of the mining companies was to keep the mostly-immigrant miners in the region.

In a paternalistic setting, the mining companies provided housing, medical care, and a small acreage of farm land so that families dominated by women would be happy in this wilderness setting and reluctant to leave the area during economic hard times.

For the vast majority of both immigrant and non-immigrant women, there was little concern to provide employment for women as it was seen by many males to be the wife’s “duty to stay at home” raising the family and tending the garden.

In the mining communities, women–usually immigrant women–raised their families and found employment around the home. On their home lots they could keep a cow producing milk, cream, butter and cheese, eggs from home-kept chickens, and potatoes grown in rented acreage at the edge of town.

Once their home larders were filled, they sold the surplus door-to-door. Taking in boarders provided additional financial resources for the family, at times nearly surpassing their husband’s mining wages. As some miners decided to maintain farms close to the mines, their wives and children found on-site employment raising produce for family use.

On a commercial level, a few women worked in stores with their husbands and when the latter died, the store was taken over by the women; others operated boarding houses.

For a more statistical look at female immigrant employment we can turn away from the Copper Country and look at Gogebic County’s three important communities–Bessemer, Ironwood, and Wakefield–for an analysis provided by the 1910 census. It shows that some of the young immigrant females were using their developed skills to provide new lives for themselves, in many cases away from the home.

In order to help Finnish women, Mina Valli wrote a bilingual cookbook, titled Keittokirjä/Cook Book instructing Finnish immigrant women “trying to get along” with what to cook in an American household. The book is filled with both Finnish and American recipes from fruit soup and liver pudding to Maryland chicken and beef roasts. It was extremely helpful and in 1923 a third, revised and enlarged edition was published.

In these three communities, the boarding house category attracted the largest number of women, and although not identified as male or female keepers there were 58 of them. However another 23 women were listed separately as boarding house keepers. There was even a woman listed as a hotel landlady.

The cleaning business attracted 32 women, while from home four worked as seamstresses and fourteen as dressmakers. Women entered the workforce as servants (106), chambermaids (2) and doing house work for private families (3).

The food service industry attracted a boarding house cook, two hotel cooks, and five waitresses. Finally, in the field of skilled occupations there were: one in nursing, two midwives, fourteen teachers and one telephone operator hired for their language skills.

The other concern erupted when the Crystal Falls Woodenware Company opened its doors in March 1903 in the middle of the Menominee Iron Range. The inventor of the butter dish machine and manager of the plant, Frank E. Lucas employed both men and women and produced 40,000 wooden butter dishes per day and clothes pins.

By the summer of 1906 as the company flourished, providing work for 40-50 men and women, there was a demand for expansion and additional laborers were sought. However, Lucas found that the “amount and quality of laborers” was lagging because of the “great demand for laborers in the mines.” So we have another reason why factories avoided development in mining regions.

Eventually the Escanaba Woodenware Company saw its woodenware department destroyed by fire in 1907, and the Crystal Falls operation was sold and the machinery dismantled and shipped to the non-mining community, where there was a labor surplus.

In the Copper Country, communities without major mines and within city limits like Hancock and Houghton saw businessmen and commercial interests actively seek to attract industries to improve their local economies.

In 1910, D.A. Stratton, general manager of the American Handle Company visited Houghton, conferred with businessmen in regard to the establishment in Houghton of a factory for the manufacture of wooden handles for a variety of tools, and the reporter wrote “there is said to be a strong probability of the factory being located here.”

At the time, the Fennia Manufacturing Company approached the city of Hancock seeking a factory site with property valuation from the council. A butter dish factory moving to Houghton was not opposed, and this would be the case in Calumet.

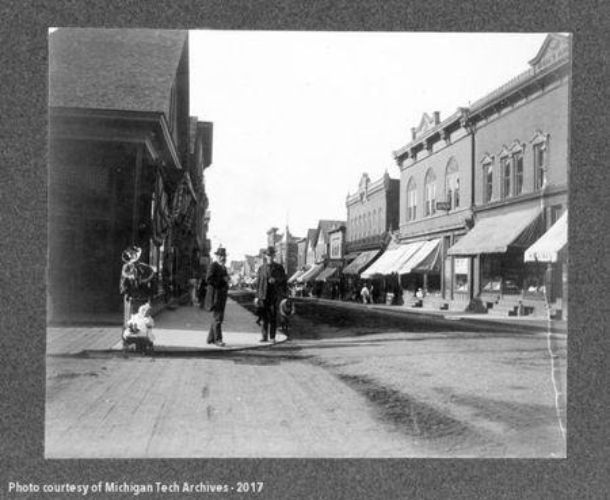

Fifth Street, Calumet, Michigan, c1910

Now we direct our attention to female employment in Calumet, the mining bastion of the Upper Peninsula.

Mine owners on the iron ranges and especially the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company in the Copper Country saw that they were the dominant industry and had little fear from competition in the form of competitive factories. They dominated the labor force and few companies sought to enter the job market of this giant.

Naturally there was no concern for women having employment outside of the home and that they too could be seen as a large stable labor force. Furthermore, the reality that the mining ranges were far from metropolitan markets and transportation hubs kept factory owners from looking north, unless an industry could develop around forest resources.

However small, non-competitive industries in the service field entered the heartland of the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company. In 1896, M. Kittler operated a mattress company in Laurium where in 1906 there was Jacob Warshawsky’s Laurium Mattress Company along with a carriage factory and the Calumet Bedding Company, while across town the Calumet Garment Manufacturing Company was in operation in 1914 and into 1920 with John P. Peterman, president and Philip E. Peterman, secretary-treasurer.

However, as early as 1896 the problem of not having factory work for women and young men not going into mining surfaced. George H. Miles, real estate agent in Calumet, advertised in the Calumet News that the “rising generation” of young adults cannot find work and must leave the area. He encouraged families to move to Munising to farm.

He pointed out the inducements for usually money-strapped miners, many of whom had farmed in the Old Country: reasonably-priced land, easy terms, good prices for timber for charcoal wood, and good prices for surplus produce for ready markets. It is obvious that the Copper Country needed non-mining jobs.

Luella M. Burton, a deputy state labor inspector for the Michigan Department of Labor, had been in this position since 1903 and her major concern was the working conditions of women and children. She visited the Copper Country for two weeks in August 1911, looking into labor conditions as they concerned the hours and conditions of employment of women and children.

She wanted to see that “the fifty-four hour law for women is enforced.” During her inspection tour she visited several of the large department stores and other stores and on the whole was well pleased with conditions existing, stating that she found the larger stores well-equipped in every respect for the comfort of their employees and that the majority of the stores were living up to the letter of the law.

Burton found that one of the department stores allowed each of its female clerks one forenoon each week in which to rest up and she commended this innovation.

In her interview with the reporter she continued:

What particularly struck me in the copper country is the lack of factories affording employment for girls and young men. Nowhere else in the state can so large a population [c60,000] be found that has no industries of a diversified nature, where girls may find employment, and therefore the latter are obliged to accept work under harmful conditions. A good industry would be as good almost as a Young Women’s Christian Association, and would do away with girls working in saloons, as I have found them in Calumet. I have been wondering why an overall factory would not be a paying proposition here. There are a great many overalls worn by the miners of the copper country, and there would be a market, I should think, for all that might be manufactured.

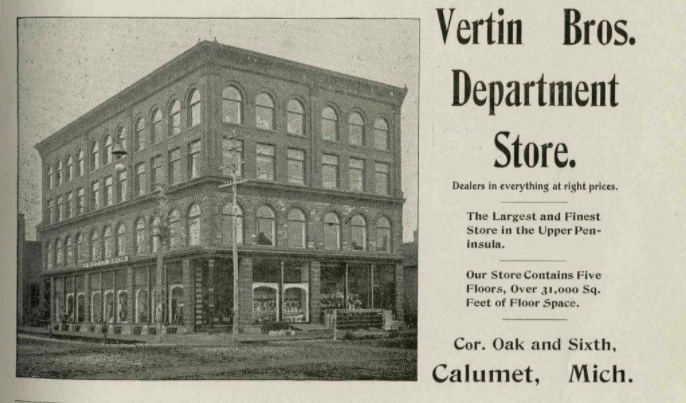

The Vertin Brothers Department in Calumet was opened by John and Joseph Vertin in 1885, offering something for anyone–from a miner to a millionaire. It grew to be the largest department store in the Upper Peninsula.

As with department stores, the majority of their workers were women. A few names surfaced in 1897: Beatrice Ferguson, a trimmer in the millinery department; Miss M. Brown, in millinery who traveled to Chicago to order spring styles, and Kate Torreano who was in dry goods and lost and found.

Employees were honored. In May 1897 when Mary Soddy died, the Vertins closed the story for part of the afternoon out of respect for her daughter who worked there. Dances were given by the clerks’ office frequently. It seems that camaraderie existed in the store. It closed in 1985, a decade after the mines closed.

The idea of establishing a clothing manufacturer in the Upper Peninsula had merit. By the spring of 1910 it was reported in the newspapers that workingmen’s shirts and clothes annually produced in American prisons was a $12 million industry. It was known that in 1913 that the state contract to make overalls at the Marquette Branch Prison was going to end.

By coincidence in 1912 the Mohawk Overall Factory at Detroit was seriously talking of locating a branch in Calumet. It had a ready market for its product throughout the Upper Peninsula and there was a stable local workforce in the area.

Its manager and owner, Joseph Decker, who was formerly from Calumet arrived in February on a business trip and returned in the summer and met with business leaders who were interested in the project. The market was at hand and competition from the prison was ending. The plant would employ about 50 stitchers paying them $10 per week.

It is obvious that this proposal worked well for the company that was hiring beginners at $16 a week in Detroit. This looked like an ideal industrial project that would fit into the Copper Country. Unfortunately subsequent information is lacking. However, it is an example of the type of factories that were welcome in mining country and would provide jobs for women but would not lure miners from the mines.

In the mining town of Negaunee, Joseph (1868-1935) and Ida Lowenstein, natives of Bauka, Latvia settled in Negaunee where they engaged in general merchandising. Lowenstein opened his department store in 1916. Originally he wanted to sell dry goods and groceries in the basement. Ida wanted to sell fashions and sundries in place of groceries, and she won the brief debate. In 1930 two of their sons were salesmen and two daughters were saleswomen, but they hired local women to work in the store as well.

Fredrick Braastad (1847-1917) was a Norwegian immigrant who settled in Marquette County in 1868 and settled in Ishpeming in 1877 and worked and developed a meat market and general stores. In 1888 he had a two-story store built that could be called an early department store.

By 1903 he was selling clothing, dry goods, groceries and furniture and a real department store came into being. At this time the building was expanded. His son Arvid became manager, but after Frederick’s death in 1917 the business declined with groceries phased out in 1919 followed by dry goods and furniture.

During the years the department store flourished, the Braastads hired women as their clerks. The building was purchased by the city of Ishpeming in 1920 and eventually became the location of the Gossard plant.

As we focus on the city of Ishpeming, which would become home to the Gossard plant, in 1910 it had a population of 12,448. The state of Michigan Bureau of Labor reported there were 41 women working in Ishpeming in 1908. Ten were engaged in food service: meats (4), bakeries (3), and soft drinks and beer (3). Ten were working in clothing (7) and laundries (3).

The majority were employed as clerks and receptionists in a variety of businesses. Within the decade the Michigan Department of Labor found that there were 77 women employed in a variety of occupations, but none of them were factory workers. Half of the women or thirty-nine were hired by clothing and chain stores: Gately-Wiggins Clothing (5), S. & J. Lowenstein (4), J.C. Penney (4), Joe Sellwood (general merchandise, 5), Skuds’ Store (dry goods, 8), Style Shop (4) F. W. Woolworth (9).

The four hotels in town hired twenty-eight women as clerks, chambermaids, cooks, dishwashers, and waitresses and seven women were working at the Nelson Dairy lunch counter. The remaining sixteen women were working in a variety of jobs from the Grand Union Tea Company to the Red Cross Drug Store.

Ishpeming had developed a number of small companies. In 1920 the Home Industry Glove Company was in operation employing women. There was also the Ishpeming Toy Company using the local wood supply, but ended in bankruptcy in June 1922. It was taken over by the Holbrook Manufacturing that produced hardwood kitchen tables.

The mining companies who usually dominated the local business scene did not promote competitive industries here as well. However, this was not the case when the H.W. Gossard Company based in Chicago, the maker of women’s corsets, girdles, brassieres and undergarments, decided to locate a plant in Ishpeming. The opening of the plant in 1920 proved the point that women in mining areas were eager to find factory employment.

It usually hired single women and newly married women bringing additional economic prosperity to the community. The Gossard plant operated through the Depression of the 1930s. By the early 1950s it employed over 650 people and 80 percent of them were women. The factory even opened a branch in Gwinn, a neighboring mining community.

The Gossard building c 1904. Ishpeming, Michigan

The Gossard factory became the Midwest’s largest employer of women north of Milwaukee. It closed on December 31, 1976. The closure of this plant ended a long history of factories employing women in the Upper Peninsula, which began in Marinette-Menominee in 1907, but many of the longest and most successful were in non-mining areas – Sault Sainte Marie, Menominee, Marinette, and Escanaba. The Gossard plant was the only successful factory on a Michigan mining frontier.

A Gossard Girl at work, Ishpeming, Michigan.

A similar experience in female employment took place on the Minnesota Iron Range. After World War II, Cluett Peabody & Company moved into the mining community of Eveleth, Minnesota to produce Arrow brand shirts and underwear. Before they ceased in operation in 1978 they provided jobs for women on the Iron Range.

There was an attempt in 1948 by Howard H. Billings, president of the Iron River Business Men’s Association and Mayor E.J. Wittock of Stambaugh to try to get the H.W. Gossard Company to locate an additional plant in Iron River. They went to Chicago and conferred with the president and production manager of the Gossard company. This was in response to the company’s program to expand their operation.

Additionally, during this post-World War II period people on the iron ranges could see that there would be an eventual decline in iron mining, since the richest ore went into the war effort. They promoted the idea that Ishpeming had a successful plant and that Iron River had a similarly stable labor market and there was the potential of 1,570 women interested in factory employment.

If their invitation was successful, the Gossard plant would need 60,000 square feet of space and an investment of $750,000. Unfortunately this attempt to bring industry to a mining range was too little too late, as the mines were in decline and the young adult population without a non-mining industrial base for jobs was leaving the area. Unfortunately, nothing came of this effort.

By the 1970s life and the economy of the mining frontier had dramatically changed. Most of the mines had closed, people had been leaving the area since 1920 for the auto industry in Metro Detroit and elsewhere and there was no longer a demand to develop alternative industries that could hire women. Any new industrial development, if it could be attracted would be hiring both men and women but distance and resulting transportation problems were obstacles. In 1951, the American Playground Devise Company of Anderson, Indiana, manufacturers of beach, pool, picnic, gymnasium, and playground equipment, bought Nahma.

Located on the shore of Lake Michigan, this near-ghost town had been home to the Bay de Noc Lumber Company. American Playground figured it could easily expand and there were 4,300 acres of available timber. In 1968-1969 the company moved from Anderson and sixty employees relocated northward.

Unfortunately, the project died within a few years as there were difficulties efficiently shipping playground equipment through the rail labyrinth of Chicago, and the American Playground left the Upper Peninsula.

It is the goal of the author to provide the reader with insights into this little-studied and nearly-unknown aspect of Upper Peninsula labor history.

In mining and non-mining regions women were a stable labor force that could have been developed if the right elements were available for the development of industry.

Women–especially younger women–wanted to work and to be able to have financial independence, and this is what made the Gossard experience a success.

Investigate Daggett. My Grandfather and Grandmother operated the Daggett Mercantile there.

Enjoy your post.

I did not see the name of Levine brothers that operated a department store in Negaunee Michigan.