History Behind the Fence: The Marquette General Hospital Complex

In the past few weeks Adamo Demolition of Detroit has been removing asbestos from the old Marquette General Hospital, formerly known as St. Luke’s Hospital and recently surrounded the site with a cyclone fence. So what is the history of the hospital site with its labyrinth of buildings and tunnels constructed over the decades of the twentieth century? What follows will provide the reader with the historical significance of the buildings and especially the older structures, some seen and unseen absorbed into newer structures.

Until the late 19th century patients needing hospital care were placed in rooms of the attending physician’s home. Then in July 1896 the Marquette City Hospital opened at 152 E. Prospect near the street car line for easy access with cold and hot water in the bathroom. Without an elevator, Superintendent Frank Stolpe carried patients up and down the stairs on his back! In June 1897 the hospital moved to 123 W. Ridge on the site of present Peter White Public Library property.

As a result of these inadequate facilities, a group of physicians led by G.J. Northrup and A.A. Foster decided to organize in 1896 and push for a modern hospital. As a result in June 1897 St. Luke’s Hospital was incorporated as a charitable, non-profit and non-secular corporation. It is first board of directors included Marquette founding father Peter White, Episcopal Bishop G. Mott Williams, Dr. A.A. Foster, Judge J.W. Stone, John M. Longyear, Alfred Kidder and A.E. Miller all important leaders in the Marquette community. The Episcopal church played a role in the development of this corporation. The hospital commemorated the apostle and gospel writer St. Luke, a companion of St. Paul and “beloved physician.”

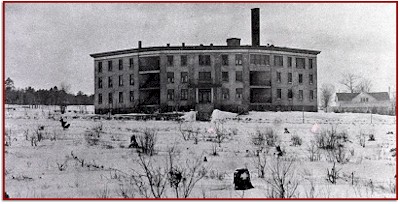

It was not until 1912 that plans and finances were developed and construction on the new hospital could begin on open land, a block from Northern State Normal School (now Northern Michigan University). The land was a city block bound by Hebard Court on the east, Lee Street on the west that would be eventually closed with the expansion of the facility, W. College Avenue on the north and W. Magnetic on the south This city block was donated by John M Longyear. It was the first modern hospital facility established on the site or as it was reported, “It will be modern in every particular and will incorporate the most advanced features of hospital design.”

When the three-story fireproof structure opened for service in January 1915 with a 65-bed capacity, a laboratory, two operating rooms, obstetrics department, two x-ray rooms, and a pharmacy. There was also “the latest electronic elevator operated by a push button control” and there were two bath and toilet rooms for each floor.

The name “Hebard Court” has little reference to the city of Marquette, so who was it named for? Hannah M. Hebard (1862-1929) “of Philadelphia and Pequaming, Michigan” provided the largest sum – $27,000 (Value today: $880,727) – for the hospital. She was the wife of the nation’s most prominent lumberman of the era, Charles S. Hebard (1861-1931).

Sixteen years later the Northern Michigan Children’s Clinic was established on hospital grounds through the vision and philanthropy of one of Michigan’s honored citizens, Senator James Couzens (1872-1936). Couzens had played a fundamental role of the birth and development of Ford Motor Company by first investing $2500 and then carefully supporting the development of the company. When he departed from the company, he sold his stock back to Henry Ford in 1919 for $30 million (value today $546,727,109). A philanthropist, Couzens donated much of his wealth to civic causes especially those relating to children. In 1929 he established the Children’s Fund of Michigan with a $10 million (value today $178,426,315) grant intentionally planned to end after 25 years. The fund allowed Michigan children to receive health and dental services.

Marquette received the benefit of Couzens’ philanthropy. Established on the grounds of St. Luke’s Hospital was Northern Michigan Children’s Clinic. At the dedicatory exercise on June 11, 1931, Governor Wilbur Brucker said, “the Northern Michigan Children’s Clinic is a marvelous addition to the jewels which are Michigan’s.” A.G. Ruthven, president of the University of Michigan, pledged “continuous cooperation of the University in this service to society.” Throughout the years the pledge was kept. The trustees of the Children’s Fund of Michigan with William Norton as its executive director operated the Clinic for almost 25 years ending its responsibilities on May 1, 1954. At that time according to the original agreement made in 1931 the clinic building and its furnishings were assigned to St. Luke’s Hospital. This building played an important role during the severe polio epidemics of the 1940s and early 1950s. Here Max Reynolds made national history by building a wooden lung for polio paralyzed patients. The Clinic had eight lungs and St. Luke’s was the second largest “lung” hospital in the United States. Unfortunately, the building was demolished when the East Building was built in the 1984; it would have been located about 50 yards west of Hebard Court on W. College Avenue.

St. Luke’s Hospital School of Nursing began in 1898 with one student, Mary Munn. Enrollment grew to 72 students enrolled in a three year program licensed by the state of Michigan. The school was affiliated with Northern Michigan College, where the nurses received their basic science training. Eventually in 1974 this school of nursing was absorbed by Northern Michigan University’s School of Nursing having graduated 700 registered nurses many of whom served the Upper Peninsula.

In the early days nurses found housing at a home on the corner of W. College and 4th Streets or on the 3rd floor of the original hospital. These were inadequate rooming spaces. Onto the scene came a brother and sister, George and Margaret Wallace. The family had made its money in the Lake Superior Power Company where George was an important salesman for the company on the Menominee Iron Range. After the death pf her brother in 1931, Margaret donated $40,000 (today’s value $802,918) to the construction of the Wallace Nurses’ Residence. She also donated $20,000 to the hospital fund. The residence opened in June 1935 and faces W Magnetic Street. In 1940 an addition to the residence was to be built.

Portions of a tour made by a reporter for the Mining Journal provides the reader with interesting details of the interior of the structure that was well-appointed. “As you enter the front door and turn down the hall to the right you are admitted to a big living room with a fireplace in pale yellow brick and ivory walls. Above the fireplace hangs a lovely big Lundmark painting of Lake Superior.

In a small room between the entrance door and the living room is the office with its buzzer system for calling the nurses. At the other side of the entrance is a cloak room, and beyond a reception room, a supervisor’s room and the library. Down in the basement is a huge recreation room with a handsome fireplace with maple mantle. There is a classroom for demonstrations, a laundry room with linen shut, a maid’s room and well-appointed bath room. And with the big sewing room, chemistry laboratory and dietitian’s laboratory there is a fine plant available for the work of the training school, as well as the recreation and home angles. The second and third floors are given over entirely to the nurses’ rooms.” There were rooms for 42 nurses.

On each floor is a supervisor’s bedroom, with maple furniture similar to that in the nurses’ rooms except that these rooms have a secretaire instead of the table desk, an arm chair, and bedside table. Each of the floors, too have a large tiled bathroom equipped with a tub and two showers, in addition to the private bath in the supervisor’s room. All the corridors and the basement floors are in mastic/ceramic tile and window and door sills are in marble.

Opening off from the third floor at the back is a big space on the roof enclosed by a low parapet which makes an admirable place for the girls to sit and study, play games, and rest in the sunshine. There is a beautiful view from all the bedroom windows, but there is a superb view of the whole surrounding country from the vantage of this outdoor roof-garden.” Its last used was administrative offices for Duke-LifePoint. The main doorway will be removed and preserved.

The demand for expanded medical facilities at St. Luke’s grew. In 1937 the trustees announced that a $100,000 building would be erected during the summer on the hospital grounds next to the Northern Michigan Children’s Clinic with an additional $50,000 provided by the Children’s Fund of Michigan. It was named the “James Couzens Memorial” or “JCM.”. The architects were the noted Detroit firm of Smith, Hinchman and Gryllis and they used a Georgian style of architecture to blend in with that of the nurses’ home.

The new unit was a fireproof three-story building with a full basement. It was located west of the Children’s Clinic and the two buildings were connected with an underground corridor. The structure was L-shaped and designed to be enlarge when necessary. On the third floor of the new unit as a maternity ward and babies’ nursery. Part of the building was used for isolation of contagious disease cases. During World War II the U.S. Selective Service contracted with the hospital to provide induction tests and at its height 300-400 men were tested in a single day at $3 per patient. This ended in early 1945 when induction testing moved to Milwaukee. Today portions of this brick structure are embedded and surrounded by the modern structure on W. College Avenue.

In April 1965 the board of trustees announced an expansion of the hospital at the cost of $2,250,000. The expansion concentrated hospital activity in a well-planned complex of medical and surgical services, which made for greatly improved efficiency. The new construction faced Lee Street (later closed) and was designed by architects Schmidt, Garden & Erikson of Chicago. The project included a one-story addition linking the new structure with the Couzens portion and the Wallace Nurses’ Residence. The laboratory and physical therapy departments located on the third floor of the 1915 building were re-located in the new building. As the Mining Journal reporter said, “They will no longer be isolated from the patients’ served by the required use of two elevators and a network of basement passageways between buildings.” The radiology and medical records department in the basement of the Children’s Clinic and the pharmacy and emergency departments were moved to the new building from the basement of the Couzens building. A new ultra-modern obstetrical patient unit was located on the third floor, connecting with the delivery suite. Here were located labor rooms and a rooming-in-accommodations for mothers who preferred to have their baby remain with them in the hospital room. New patient rooms replaced smaller, out-moded rooms in the original hospital. An intensive care unit was constructed in the modernized Couzens building. A one-story addition housed expanded space for the central supply department and new recovery room adjacent to the surgical suite. Finally, a new power plant was constructed. This rather massive development was opened in 1969.

In 1973 St. Luke’s merged with Marquette’s other hospital, St. Mary’s, the Catholic hospital built in 1890 and operated by the Franciscan sisters. After the merger it was remoderned by the state of Michigan and became the D.J. Jacobetti Home for Veterans. Efficiency had arrived as duplication of services ended and the newly named Marquette General Hospital could up-grade it’s medical services for the Marquette community and beyond.

The South Tower was the centerpiece of a major renovation and expansion project started in 1979 and completed two years later. The eight story structure held 194 patient beds, a new emergency department, laboratory and operating room suites. In 1984 the East Building opened on the site of the old Children’s Clinic. It housed the radiation therapy department, hemodialysis and endoscopy units, medical library, conference center and oncology unit. In 1987 MRI magnetic resonance imaging) was introduced here. Marquette General Hospital continued to build to meet medical needs and in 1992 it opened the North or Robert C. Neldberg Builiding costing $40 million and the much needed parking structure. The Neldberg Building, 200,000 square feet housed both In- and Outpatient Admitting, three Cardiac Catheterization labs, Outpatient Cardiac Unit, CCU, Rehabilitation Services, The Family Birthing Center, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and Behavioral Health Services.

Robert C. Neldberg (1931-2015) an Iron Mountain native was named the CEO/administrator of the hospital in 1974 and retained the position until his retirement in June of 1996. During his tenure as CEO, growth of the medical staff from 40 to 200 brought well trained specialists to the UP for the first time allowing the formation of the Heart Institute, Cancer Center, Behavioral Health Center, Rehabilitation Center, Neuroscience Center and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Growth of the hospital’s workforce from 660 to 2400 was a great source of pride including the fact that there had not been a lay-off during his watch. Under Bob’s leadership there were many “firsts”: first cardiac cath’ lab in 1977, first open heart surgery in 1978, first CT scanner in 1979, first linear accelerator in 1984 and one of the nation’s first MRI’s in 1987. He was honored at his retirement with the naming of the Robert C. Neldberg Building (formerly the North Building).

A $15.5 million Bridge Building/Skywalk connected the north complex with the South Tower on the third floor level and opened in 2000. An ICU on the fourth floor and the Upper Michigan Neuroscience Center occupying the third floor. At this point Marquette General Hospital consisted of a massive complex of structures built over the years amounting to millions upon millions of dollars, a labyrinth of underground tunnels and modern facilities that you needed a map or guide to get to the location you sought. Many of us remember this situation quite well.

As the new 21st century progressed financial difficulties were on the horizon. Marquette General had a long-term debt of $60 million and pension liabilities of $100 million. As a result it was decided to sell Marquette General Hospital in 2010, a century after plans were laid for the first modern hospital. Two years later it was purchased by the for-profit Duke LifePoint Healthcare. Upon its purchase of Marquette General Hospital, Duke LifePoint renamed the hospital to UP Health System – Marquette. In 2014, Duke LifePoint announced plans for a new hospital complex, located on West Baraga Avenue, to replace the Marquette General Hospital campus. The construction of the new hospital was funded by Duke LifePoint, as required by the purchase agreement.

The new UP Health System Marquette opened in 2019, with most services moving to the new building. As of December 2022, some services remained on the old Marquette General Hospital campus, which is scheduled to be fully vacated by early 2024. The property was sold to the Northern Michigan University Foundation for $1.00 and is slated for redevelopment. Demolition of the structures should begin in the late summer of 2023, thus the fencing that you see. Even the curious must observe the “no trespassing” signs and keep out of danger. Observe from across the street.

There’s a lot to enjoy and learn in Russ’ scholarship. What I appreciate in this telling of the story of our hospital is the philanthropy that made each stage of growth possible. I like to think such civic generosity comes from a duty, among those with “extra”, to create and sustain a culture of health and liveliness in our rugged rural home. Our growing arts and creative scene benefits from the same flow of generous grace.