The Jesuits Open the Upper Peninsula to the World

The Society of Jesus, better known as the Jesuits, played an important role in opening the Lake Superior country to French colonization. They were part of a four-pronged force–explorer, missionary, fur trader/voyageur, soldier–that brought the French into the Mid-Continent. Of the four, they have left the world with the greatest knowledge of the environment and people of the region in the 17th and 18th centuries.

So first we must trace the Jesuit origins and an aspect of their philosophy of learning. The Roman Catholic order was created in 1540 to revive Catholicism through education. One of the early Jesuits, Jerónimo Nadal set the tone of their outlook when he wrote his conferes that “the whole world becomes our house” on the journey that they would take.

These men were not monks who lived isolated in monasteries working and praying, but they embraced the world. Their journey into the world saw them establish some 700 institutions under their supervision, which long provided an institutional framework housing both science education and research. The Jesuits used the scientific method in their evangelization ministry as surfaced in the Lake Superior country.

The first Jesuits – Charles Raymbault and Isaac Jogues – reach the Ojibwe/Anishinaabe at their village of Batating at modern Sault Ste. Marie in October 1641. The Jesuits had been invited to their village and there was talk of establishing a mission. After a brief stay of these Jesuits they had to continue their work in Huron country to the east. Other Jesuits would passed through the Sault on their way to Chequamegon Bay at modern Ashland, Wisconsin.

It was Claude Allouez who preached among the Indians in 1667 who named the river and rapids Sainte Marie. Jacques Marquette was sent there and established the Mission of Sainte Marie/ St. Mary in 1668 a strategic point between Montréal and the eventual Holy Spirit mission at Chequamegon Bay. Also it was home to a concentration of Ojibwe and many other tribes who visited the site because of its excellent fishing during the summer months.

It was the specific task of the Jesuits was to evangelize the Native People. In order to conduct their successful ministry they learned native languages and recorded the geography, environment, and the people of the new lands they entered. Their chronicles have reached us through the Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, which are a collection of letters and reports along with a few individual books penned by some Jesuits.

There is no rival to these accounts except for a few military reports written by soldiers like Commandant Cadillac who founded Detroit in 1701. They acted as cartographers, ethnographers, chroniclers, naturalists or promoters and agents of expansion for the French government. This work in the Lake Superior Country started in 1641 and continued through their suppression in 1773.

The Jesuits operated out of a number of missionary centers – Mission of the Holy Spirit at Chequamegon Bay (modern Ashland, Wisconsin); St. Mary Mission at Sault Ste. Marie; two missions at St. Ignace: Mission St. Ignace (named after their founder Ignatius of Loyola) and Mission St. François Borgia; Ste. Anne church at Fort Michilimackinac; and St. François Xavier at Green Bay. These stations were religious in nature but also contained libraries and were early literary centers where Jesuits wrote their chronicles and letters before sending them east to Québec City and on to France for editing and publication.

First we see them as explorers of the Lake Superior region as they sought new Native tribes to evangelize. They kept and published elaborate chronicles to be used by missionaries who would follow them. In the Relation of 1666-1667 Claude Allouez said that “. . . he had journeyed, in all his travels nearly 2,000 leagues [approximately 6,000 miles; a league is approximately 3 miles in length], through vast forests – enduring hunger, nakedness, shipwreck, weariness by day and night . . . .”

Accompanied by two Native guides he crossed a portion of Lake Superior in a canoe, “paddling for twelve hours without dropping the paddle from the hand.” That May 17th, 1667 was a day of exceptional calm. If a storm had arisen it would have placed them in the gravest danger.

Traveling from Sault Ste. Marie to Chequamegon, Marquette wrote that it took him one month from mid-August until September 13, 1669 “amid snow and ice, which blocked our passage and amid constant dangers of death.” And we talk of climate change today!

Inclement weather was unavoidable, but Jesuit explorers made careful and elaborate plans prior to embarking on a voyage of discovery and exploration. Marquette reported that he learned of the “Great River” – the Mississippi River from an Illinois youth he met at Holy Spirit mission. The fellow taught Marquette the Illinois language, their customs and the nature of the land. He and the French were intrigued because the river possibly flowed into the South Sea as the Pacific Ocean was known and thus a route to China their ultimate goal.

As a result, the French government ordered an exploration of the river and put Louis Joliet in charge. However, he needed an individual who was generally familiar with the route and the people they were going to encounter. As a result he arrived at St. Ignace in 1672 and told a rather surprised Marquette that he had been ordered to undertake a new mission – exploration of the Mississippi River.

The Jesuit provides us with how an explorer prepared for such an expedition.

Marquette wrote “and because we were going to seek unknown countries, we took every precaution in our power, so that if our undertaking were hazardous, it should not be foolhardy.” He continued:

“We even traced out from our reports on a Map of the whole of that New Country; on it we indicated the rivers which we were to navigate, the names of the peoples and of the places through which we were to pass , the course of the great River, and the direction we were to follow when we reached it.”

Having developed his valuable knowledge of the land they were going to enter, Marquette and company were not deterred when the Menominee told them that it was a near-impossible task and they would encounter monsters. Unfortunately, this document is lost to us.

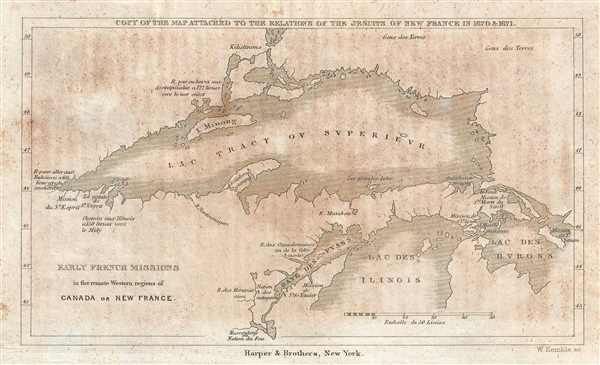

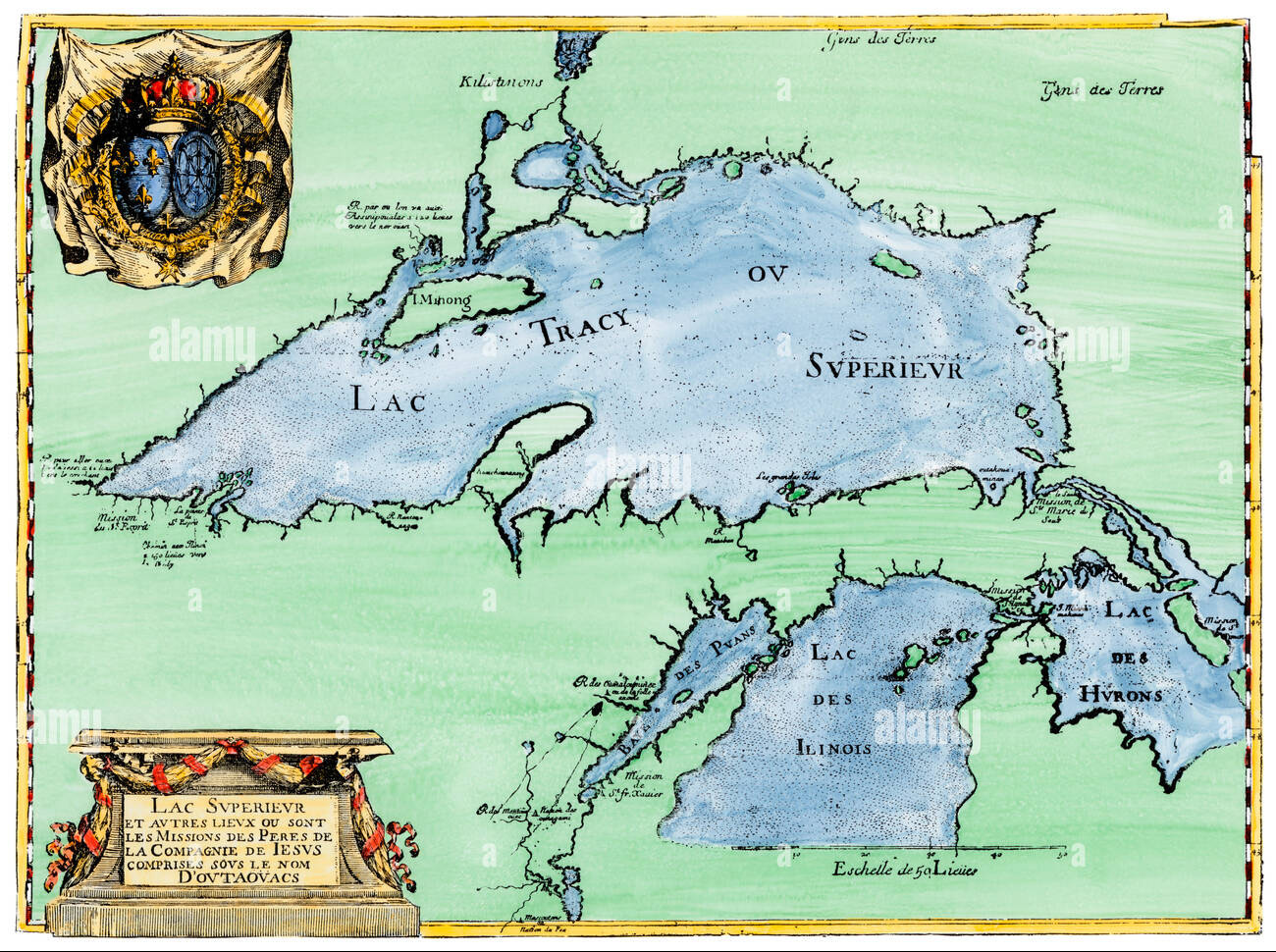

Lake Superior, the highway to tribes along its shores and beyond into the west attracted Jesuit attention and was the most studied of the Great Lakes. As a result the missionaries, Claude Allouez and Claude Dablon, “who had considerable intelligence” decided to undertake the creation of a map of Lake Superior and they were most concerned about the exactness of their work. Their general rule was to include only those geographical features that they had actually observed. Between 1665 and 1667 the two Jesuits explored the entire shoreline of Lake Superior.

The Jesuit map of 1670 of Lake Superior has been praised by scholars over the years as a “faithful representation” of the region or as cartographer, Louis Karpinski wrote:

“In the Relations of 1671, published at the famous Cramoisy press in Paris, there appears a remarkable delineation of Lake Superior. This map bears eloquent witness to the high scientific attainment of some of the Jesuits as the map clearly involved numerous scientific observations.”

—

In 1665-1667, Allouez left a detail description of the lake:

The form of this Lake is nearly that of a bow, the Southern shore being Much curved, and the Northern nearly Straight. Fish are abundant there and of exceptional quality; while the water is so clear that objects at the bottom can be seen to the depth of six brasses [or 36 feet].

He also pointed out that since there were few islands in the lake, the wind could “stir up with as much violence as the Ocean.” Two French fishermen in the autumn of 1669 were caught in an unexpected storm and perished.

In the northeastern section of the lake they found Michipicoten Island and wrote of the Native stories and myths about copper and monsters connected with the island. Isle Royale was described as “large and is fully 25 leagues long; it is distant seven leagues from the mainland [of Minnesota] and more than sixty from the end of the lake [modern Duluth].” They found copper on the island and returned to Québec with specimens.

In the spring of 1669 Allouez brought two-foot long pieces copper weighing one hundred pounds to the capital. He also related that there were copper samples to be found in the Odawa corn fields at Chequamegon some half league from the shoreline. Pierre Charlevoix on his voyage to the interior, encountered a nameless Jesuit who had been a goldsmith before joining the order and while stationed at Sault Ste. Marie worked the copper he found into candlesticks, crosses, and censers for burning incense for church ceremonies. In 1879 one of these items was uncovered in the Green Bay area.

The Jesuits described the principal foods of the Lake Superior region – blueberries, wild rice, and many varieties of fish and first brought them to the attention of Europeans. Louis André who was stationed at times in the Upper Peninsula has left us with a description of what could be best described as “survival food” found on the trail:

“All those people [Native People] had for some time been suffering from a famine, and I found them reduced to a fir tree diet. I never would have believed that the inner bark of that tree would serve as food, but the Savages told me that they liked it. I know not whether it would always be so, but I do know very well that, when hunger forced me to seek some sort of food to keep me from dying, I could not swallow fir bark. I did indeed eat some bark of another tree, and hunger made me find therein the taste of bread and the substantial quality of fish; but my stomach has become used to other and much more meager viands that the above, and even to dispensing almost entirely with food for a considerable time.

I know not what my predecessors may have suffered in their country, but I proved well enough by experience how far one can go without quite dying of hunger. My daily allowance of food was not given me until after Sunset; and if there were any bad morsels it was sure to be reserved for me, – while even that was so small in quantity as hardly to suffice for sustaining life. To such straits we were reduced by ill success in fishing and hunting that Year [1670] . After causing a thorough but ineffectual search in all the cabins for a bit of smoked meat, I decided that I must resort to every experiment to avoid dying of hunger. Therefore, I went into the woods as did most of the Savages, to hunt for roots, acorns, and a kind of moss called by the French “rock tripe”; but all in vain when weakness made me believe that I was

a long distance from the cabins, so utterly had my two months’ hunger exhausted me.Then I remembered seeing the Missionaries eat the inner bark of the fir tree, and I attempted to accomplish this; but I could not swallow

it, and I returned from the woods as empty as I had set out. Entering the cabin, I was offered an excellent dish; for I was told that a piece of the door had been out into the pot. “Will you eat some if we give it to you?” I was asked. “Why not,” I replied, “if it is anything that can be eaten?” It was old moose skin with which a women who had recently arrived and was furnishing us a feast. She gave me a very little of it, and it lasted me for 24 hours. The same liberality was shown by her on the two succeeding days, but I could not eat the food; for, as usual, I had been given the worse part, and the vary pieces that had not been steeped in the kettle while it was boiling. As I had some of the Native shoes left, and some books, I had good hopes of prolonging my life therewith, – taking a little Theriac [mixture of opium and spices used as a medication] after eating such unaccustomed diet.”

It should be noted that a number of early Jesuits refused to eat Indian food offered to them. One of the Indian leaders countered that if the Jesuits wanted him and his people to accept the Jesuits’ religion then they would have to accept the Indian food. When this episode reached the Jesuit superior in Québec City he ordered the missionaries to eat the food offered to them and having taken a vow of obedience they obeyed no matter how they felt about the food.

After this lengthy discussion of the diet that missionaries were faced with, they went into detail about the new foods encountered in the north country. One was what the French called, tripe de roche or rock tripe (Umbilicaria). It is a lichen that grows on rocks and is edible when it was properly prepared: soaked extensively and boiled with changes of water to remove the bitterness and purgative properties. It was used as “famine food.”

Again André tells us of this new food that he encountered it as he approached Georgian Bay where the country “is very rugged, and little adapted to agriculture; but, in compensation, it abounds in Beavers, nothing but lakes and treeless rocks meeting the eyes of nearly every direction.” And then he went into depth about this new food:

“These rocks were of great service to me, for they are not so sterile as might be imagined, but possess the means of preventing a poor soul from starving. They are covered with a kind of plant , which resembles the scum on a marsh that had been dried up by the Sun’s heat. Some call it “moss” although it is not at all in the form of moss; others style it “rock tripe”; for myself, I would rather use the name “rock mushrooms.” There are two kinds: the small variety is easy to cook, and is much better than the large, which does not cook tender, and is always a little bitter. To make a broth of the sort, it is only necessary to boil it; and then, being left near the fire, and occasionally stirred with a stick, it is made to resemble black glue. One must close his eyes on first tasting it and take care lest his lips stick together.

This manna is perennial, and when one is very hungry partakes of it without longing for the fleshpots of Egypt. It may be gathered in any season, as it grows on the steep slopes of the rock, where the snow does not lodge so easily in a flat region.”

In the 19th century rock tripe was used by a number of Arctic expeditions as survival food as the men traveled south back to civilization.

André went on to discuss the oak trees he encountered and the acorns, which he said tasted like chestnuts. They had to be cooked for twelve hours and the water occasionally changed and then passed through “a sort of lye, in order to be rendered edible.” Both rock tripe and acorns provided him with food for three months while in the country. His diet was augmented with moose skins properly boiled and even some smoked meat which was considered a treat.

The blueberry (Vaccinium) has mostly circumpolar distribution in North America, Europe and Asia. So when the Jesuits wrote about it and its uses they were merely spreading the word that it existed in North America. Pierre Bailloquet was one of many Jesuits who reported the blueberry. In the summer of 1674 Bailloquet while living at Sault Ste. Marie he “lived for two months . . . with more than a thousand Savages on small fruits here called bluets [“blueberries”], which grow only on rocks or in rocky soil . . . .”

Jacques Marquette in the spring of 1673 while on his voyage to the Mississippi River took time to visit with the Menominee people in the southern Upper Peninsula, some of whom were converts. They were known as the “Wild Rice People” and Marquette took time to describe in detail wild rice (Zizania palustris) its cultivation and how it was processed. This was the first time this plant was described for Europeans:

“The wild oat [Folle Avoine or wild rice], whose name they bear because it is found in their country, is a sort of grass, which grows naturally in the small rivers with muddy bottoms, and in swampy places. It greatly resembles the wild oats that grow amid our wheat. The ears grow upon hollow stems, jointed at intervals; they emerge from the water about the month of June, and continue growing until they rise about two feet above it. The grain is not larger than that of our oats, but it is twice as long, and the meal there from is much more abundant. The savages gather and prepare it for food as follows. In the month of September, which is the suitable time for the harvest they go in canoes through these fields of wild oats; they shake its ears into the canoe, on both sides, as they pass through. The grain falls out easily, if it is ripe, and they obtain their supply in a short time. But, in order to clean it from the straw, and to remove it from a husk in which it is enclosed, they dry it in the smoke, upon a wooden grating, under which they maintain a slow fire for some days. When the oats are thoroughly dry, they put them in a skin made into a bag, thrust it into a hole in the ground for this purpose, and tread it with their feet – so long and so vigorously that the grain separates from the straw , and is very easily winnowed. After this, they pound it to reduce it to flour, — even, without pounding it, they boil it in water, and season it with fat. Cooked in this fashion, the wild oats have almost as delicate a taste as rice has when no better seasoning is added.”

The variety of fish found in the Great Lakes provided the Native Americans with 75 percent of their diet. As a result the Jesuits wrote extensively about the fish they encountered. The Straits of Mackinac “is noted in all these regions for its abundance of fish, since, in Savage parlance, this is its native country.”

There were three important fishing centers along Lake Superior’s shoreline. The first was at Sault Ste. Marie, a short distance down the St. Mary’s River from the lake, where amid the boiling waters of the rapids, fish were taken from spring until winter. The chief fish, whitefish “is most excellent, so that it furnishes food almost by itself, to the greater [several thousand people] part of all these people.”

At the mouth of the Ontonagon River in the western end of the Upper Peninsula, the sturgeon season ran from the spring until autumn and the Indians caught the fish day and night. A Jesuit chronicler noted that, in a single night, an individual using a net could take between thirty and forty sturgeon. Chequamegon was another excellent fishing location where whitefish, trout, and herring could be taken. However the chronicler ended his fish story, “. . . a full list of all its [Lake Superior’s] fisheries would require a complete enumeration of all the coves and all the River of this Lake.”

And so the Jesuit chronicler continues:

“In fact, besides the fish common to all the other Nations, as the herring, carp, pike, golden fish, whitefish and sturgeon, there are found here three kinds of trout: one, the common kind; the second, larger, being three feet in length and one in width; and the third, monstrous, for no other word expresses it, – being moreover so fat that the Savages, who delight in grease, have difficulty in eating it. Now they are so abundant that one man will pierce with his javelin as many as 40 or 50, under the ice, in three hours’ time.”

The Jesuit writings are filled with details of Indian life and culture around the lake which aid modern ethnographers seeking to learn about Indian life before it was altered by the white invasion. However it must be remembered that Jesuit value judgments about the Indians were naturally influenced by their seventeenth French religious and social background.

Once this is understood their works are a rich treasure of information. The lands around Lake Superior were home to twelve to fifteen tribes who were attracted to the lake by the excellent fishing and the “petty trade” which they carried on with each other prior to the coming of the French voyageurs and the grand trade that followed.

The Odawas and Hurons were considered “refugee Indians” whose homeland had been to the east in Ontario. They had been driven westward from their homes in the 1650s by the hostile Iroquois. The Jesuits noted them because they sought to re-establish contact with the Christian Huron and convert the Odawa living in northern Wisconsin in the 1660s. The Odawa were described as living at Keweenaw and Chequamegon Bays and traveled to Montréal in August with the voyageurs. When not trading they fished and cultivated corn, gathered wild fruit and vegetables and hunted.

There were other Native Americans living at Chequamegon Bay. Allouez wrote when he arrived that there were eight hundred men capable of bearing arms and seven different tribes numbering over 2,000 people all at peace with each other.

Of the many Native People who visited Chequamegon, the Jesuits wrote of the Illinois who came some 400 miles to the south at length. They came from the Iowa area, nearly 400 miles and had five large villages in Wisconsin, which stretched out for three leagues. The Illinois were considered warriors and brought many Indian slaves with them, which they traded for muskets, powder, kettles, hatches, and knives. This trade allowed them to continue taking Indian or panis slaves and enriching themselves.

Other Native People described by the Jesuits included Assiniboine and Cree, who lived to the north and northwest of Lake Superior. In 1670-1671 the Assiniboine were described as living in one large village or as others said in a series of villages not far from Hudson Bay about a two week journey from Lake Superior. The Cree were in contact with the French missionaries. They were dispersed throughout the region to the north of the lake. They possessed neither corn fields nor fixed abodes and were considered nomadic hunters. In the spring of 1670 they arrived at Chequamegon Bay in two hundred canoes in order to trade and return to their homes.

The Jesuits also reported on the Potawatomis, Ojibwe, Nipissings and the Dakota/Sioux. Their descriptions were the earliest known of the Native Peoples in the Lake Superior region and give the ethnologist a picture of the Indians before their lives and language changed by white intrusion.

As we have seen the Indians of the Lake Superior area did not practice agriculture. When the Jesuits arrived in the region they sought to introduce agriculture bringing seeds and fruit pits from their gardens at Montréal. When Marquette arrived at the Sault in 1668 he developed a small garden and planted vegetables and especially peas which could be dried and eaten throughout the seasons.

It was hoped that his example would spread farming among the Indians and within a year he reported that some of the Ojibwe had imitated the Jesuit effort. Later pear and apple trees were introduced from Jesuit orchards in Montréal. In the nineteenth century some Ojibwe developed apple orchards and those at L’Anse Native farmers developed farms that supplied the incoming miners with potatoes, an inexpensive local food. However, the Jesuits never introduced potatoes to the people of the region.

The Jesuits provided the French government with economic information which would prove important to French merchants and voyageurs. For instance, Henry Nouvel in 1673 noted the importance of trade at Sault Ste. Marie He also indicated that trade was so important that he would do anything within his power to stimulate trade with the Native People. Furthermore, Nouvel warned officials in Québec that the English had recently established a post in the Hudson Bay region and they had begun to divert Indian traders to the northern posts and away from Lake Superior. This information provided by the Jesuits allowed French commercial interests to take action to revive or expand their trade.

On a scientific level in early 1671 Jesuit chroniclers left descriptions of parahelia seen at Green Bay, the Straits of Mackinac and at Sault Ste. Marie. A parahelic circle is an optical phenomenon of the atmosphere. It consists of a series of colored rings which are caused by the reflection of sunlight from the vertical faces of ice crystals. These rings are colorful, but last for only a few minutes in duration. It was the trained and perceptive Jesuits who saw and described the parahelia over Sault Ste. Marie on March 16, 1671.

Two Jesuits played a role in the development of books related to the region. The first and better known of the two was Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix (24/29 October 1682 – 1 February 1761) traveler, historian and often considered the first historian of New France. He had little interest in a life of “suffering and deprivation for the conversion of Indian souls” but had a strong curiosity of life that he encountered. As a result he was sent by order of the French king, Louis XV to provide a detailed report on the French colony – New France or Canada. As a result he wrote, Journal of a Voyage to North-America which was translated into English and published in 1761.

Charlevoix arrived at St. Ignace on June 28, 1721 having traveled north from Detroit. He wrote that the old French trading post at St. Ignace called Fort Buade “is much fallen to decay, since the time that Monsieur de la Motte Cadillac, carried to the Narrows [Detroit] the best part of the Indians who were settled here, and especially the Hurons; several of the Outawaies [Odawas] followed them thither, others dispersed themselves among the Beaver Islands, so that what is left is only a sorry village, where there is not withstanding still carried on a considerable fur-trade, this being a thoroughfare or rendezvous of a number of Indian nations.”

He found Jesuit missionaries living there but with few Native American to evangelize “having never found the Odawa much disposed to receive their instructions.” He also noted that since the establishment of Detroit in 1701, Cadillac had caused many Native People to relocate south. This hurt the fur trade and many of the northern Indians traveled north of Hudson Bay where they traded with the English.

Charlevoix then discussed in detail the importance of French being located in the Straits of Mackinac:

“The situation of [Fort St. Philip de] of Michilimackinac is most advantageous for traffic. This post stands between three great lakes: Lake Michigan which is three hundred leagues in circuit, without mentioning the great bay [Green Bay] which falls into it; Lake Huron which is three hundred and fifty leagues in circumference, and is in form of a triangle; and Lake Superior, which is five hundred leagues round; all three are navigable for the largest sort of boats, and the first two are separated only by a small strait [Mackinac], which has also water sufficient for the same vessels, which may also without any obstacle sail all over Lake Erie as far as Niagara. It is true that there is no communication between Lake Huron and Lake Superior, but by a channel [St. Mary’s River] two and twenty leagues long, and very much incommoded with rapid currents, which Lake Superior and its shores afford.”

At this point Charlevoix provides us with information about Lake Superior although his mileage of distances are incorrect however he continues and focuses on the shoreline and storms on the lake:

“the whole south coast is sandy and pretty straight; it would be dangerous to be surprised by a north wind on it, and the north shore is much more commodious for navigation, it being entirely lined with rocks, which form little harbors, where you may shelter yourself with the greatest ease; and nothing is more necessary to those who sail in canoes on this lake, in which travelers have remarked a phenomenon which is singular enough.”

Concerning the lake’s infamous storms Charlevoix writes in some detail:

“When a storm is about to rise you are advertised of it, say they, two days before; at first you perceive a gentle murmuring on the surface of the water which lasts the whole day, without increasing in any sensible manner; the day after the lake is covered with pretty large waves but without breaking all that day, so that you may proceed without fear, and even make good way if the wind is favorable; but on the third day when you are least thinking of it the lake becomes all on fire; the ocean in its greatest rage is not more tossed, in which case you must take care to be care to be near shelter to save yourself; this you are always sure to find on the north shore, whereas on the south you are obliged to secure yourself the second day at a considerable distance from the water side.”

He continued, that the Jesuits had “a very flourishing church” at Le Sault de Sainte Marie or the Fall of St. Mary. Then he discussed copper in the Lake Superior region.

While at Mackinac he described the island and two other Islands to the south: Round Island and Bois Blanc Island which he described “as well wooded and the soil excellent, whereas Michilimackinac is only a barren rick, being scarce so much as covered with moss or herbage; it is not withstanding one of the most celebrated places in all Canada.”

Charlevoix did not forget to discuss the fish resources that he encountered noting that the local Indians:

“live entirely by fishing, and there is perhaps no place in the world where they are in greater plenty; the most common sorts of fish in the three lakes, and in the rivers which discharge themselves into them, are the herring, the carp, the gilt-fish, the pike, the sturgeon, the astikamegue or whitefish, and especially the trout. There are three sorts of these last taken; among which is one of a monstrous size, and in so great quantities, that an Indian with his sword will strike to the number of fifty sometimes in the place of three hours: but the most famous of all is the whitefish; it is nearly of the size and figure of a mackerel, and whether fresh or salted nothing of a fish-kind can exceed it. The Indians tell you that it was Michabou who taught their ancestors to fish, invented nets of which he took the idea from Arachne’s, or the spider’s web.”

Having spent four days at Michilimackinac, Charlevoix and his party left on July 2nd “and for thirty leagues coasted along a neck of land [Upper Peninsula] which separates Lake Michigan from Lake Superior; in some places it is only a few leagues across, and it is scarcely possible to see a more disagreeable country; but it is terminated by a beautiful river called La Manistie [Manistique], abounding in fish and especially sturgeon.

A little farther inclining to the southwest you come to a large gulf [Green Bay], in the entry of which are a number of islands, and which is called the gulf or bay of the Noquets [at Escanaba]. This is the name of an Indian nation, not very numerous, originally come from the coasts of Lake Superior, and of which there remain only a few scattered families, who have no fixed residence.”

Thus we leave Charlevoix providing a small part of his larger report that focuses on the region. Not discussed here are the details he conveyed about the Native People in the region.

The second Jesuit who developed a separate book on the environment and its inhabitants was Louis Nicolas (15 August 1634-post 1700), an all but forgotten and unique figure whose work only became known in the mid-twentieth century. He arrived in Canada in 1664 to work as a missionary and in the process he showed that he was more interested in studying the environment, the Native People and what they knew about the flora and fauna they used as food and medicine, rather than evangelizing during the years from 1664 and 1675 when he returned to France. In 1678 the Jesuits welcomed his separation from the order.

While in New France he visited and worked the area from western Lake Superior at Chequamegon to Sept Îsle on the east and south of Lake Ontario. He was the known author of Historie Naturelle des Indies Occidentales and Grammaire algonquine. However he also wrote Codex canadensis (Canadian Codex) that is “among least well known early manuscripts describing or illustrating the natural history of North America.” The Canadian art historian and his biographer, François-Marc Gagnon has noted that Nicolas was an intrepid traveler and talented linguist who was fascinated by the natural history and ethnography he encountered during his missionary work.

Focusing on the Lake Superior country Nicolas was stationed at Chequamegon from his arrival in the fall of 1668 and then return to Québec. He returned to the western end of Lake Superior and finally left in the spring of 1669. During this time he met with Native Americans who came from afar to Chequamegon, he passed through the Sault, and he seems to have traveled to Manitoulin Island at the northern end of Lake Huron to hunt bear. He was keenly observant and enjoyed dining on local animals.

In his writings Nicolas mentions “Tracy Sea.” This was the name given to Lake Superior by the Jesuits but it was never officially adopted. Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy (c1596-1670) was a professional soldier, lieutenant-general of French North and South America is was known in Canada as the man who defeated the Iroquois as a threat to the colony of New France. Nicolas wrote that the Indians called it the “Great Lake” or Kitchi-gummi.

Nicolas made some personal observations of the Native Americans he encountered. In general Native People were “great naturalists” today he would be referring to them as ethno-botanists as one of their characteristics. The Ojibwe at the Sault, Nicolas considered “the most capable, clever and handsome Indians in the world.” He wrote of the winter quarters of the Nauqués or Noquets, the Outchiboueks or Ojibwe and the Passinassioukes “just north of the Ojibwe.”

The most important food encountered – fish – but specially whitefish Nicolas wrote about, while passing through Sault Ste. Marie:

“I can say here that I have seen innumerable times the finest and most abundant fishing that can ever be seen through the great falls of the outlet of the great Lake Superior which is now called the Tracy Sea, and its outlet the Sault Sainte Marie, which is 300 leagues from Quebec at the 46th degree of latitude. In the middle of the waterfall, two men go in a canoe in which they have two kinds of poles, each one four fathoms long. One is used to stick into the ground and to hold them against the frightening turbulence of the water, the currents and the terrible rapids. These argonauts push their canoes violently into the middle of the rapids, until they arrive at places where they know that there are so many of the big white fish that the entire bottom of the water seems to be paved with them, or rather they are piled up one on the others in such numbers that they have only to their second pole, at the end of which there is a net in the shape of a cone or hood. Each time they raise it, as they do quickly, they bring up five or six large white fish.”

Nicolas noted that in less than an hour the canoe is filled with 100-120 fish. He concluded: It is hardly considered fishing if a hundred canoes are not filled every day that they want to undertake

This fishing, which lasts nearly six months every year, or never less than three.” The Native People fished at night under a fill moon. If the canoe overturned naked they swam like fish in water 8 pikes [18.6 feet] deep “and climb back into it, joking and laughing at each other about losing their fish and about their adventure, having also lost their koûabahagan, which if their pot spoon as they say, with which they scoop out the fish as if from a pot.” They usually only catch enough fish for their meals. During the spring and autumn some 2000-3000 people came to the rapids to engage in fishing and with no confrontation.

Having dined on whitefish Nicolas, could write, “It is so delicate to eat that it melts in the mouth when it is cooked simply in water without salt or any other seasonings, which are not used among the natives.” He went on writing that the Native People also smoked, roasted and cooked whitefish in its own fat.

Nicolas went on to discuss other fish. The lake trout was “monstrous” . . . “with a frightening head and mouth, capable of swallowing children.” The trout was caught under the ice with a harpoon and:

“The fisherman lying on the ice, holding his spear in his hand, whistles, sings and harangues the trout entreating it to come. He calls it Grandmother: ‘Come, come, Grandmother,’ he says. ‘Come, come, have pity on me, come feed me . . . . I will feast, I will feast, if you come here.”

For Nicolas, “The whole head is a royal dish; the eyes are better than calf eyes. The belly has a fine taste.” “A single fish one of these fish feeds, more than twenty men at feasts, where often several of them feed a whole village or a whole camp.”

Another fish common to the Upper Peninsula was the sturgeon or nahma. The sturgeon could be seven to twelve feet in length and was caught with a line, net or spear or it was beaten with rods or stoned at the foot of the rapids. Concerning the sturgeon as food Nicolas wrote that it is “excellent, very fleshy and nourishing. The end of the tail is a foot long and of a much more delicate taste than the tail of the best cod. When it is boiled more than usual it softens and melts like fat, and when it cools, this stock is as thick the finest jelly.”

He continued, “the underside of the belly has an exquisite taste.” “In its belly, there are a million eggs the size of horseradish seeds, from which the fisher make a kind of bread that smells bad; but it tastes good when there is nothing better to eat.” From the stomach a strong glue was made.

The flora of the region was also covered by Nicolas. Of the cranberry he wrote “It was at Whitefish Point on the banks of Tracy Sea that I first discovered this pretty fruit. It is a yellow and red fruit no bigger than an ordinary hazelnut, which grows on a very small low creeping shrub. Their fruit sets the teeth on edge because it is bitter. It has nothing special except its beauty. It is astringent like the blueberry.” He wrote of wild crab apples and currants. Maple trees dominated all of Canada and the UP and he went into detail about them and how sap was extracted and processed into sugar.

He was nearly overwhelmed by white pine writing, “There are places in the country where one can get millions of trees from which one would make double millions of planks and great beams which are double planks.” Glue for mending canoes could be processed from the sap.

Of the fauna Nicolas went into detail. He mentioned fish and then the animals found in the region: chipmunks, squirrels, common hares, badger, wolf, bear deer and naturally beavers. He discussed porcupines and the “stinking animal” along with caribou which inhabited the UP at that time and which he dined on. Mosquitoes he described as “thieves of patient,” “little drunks of human blood,” and “little tortures.” He concluded that “smoke is the only thing that can keep these pesky things away.”

He enjoyed animals and in two instances trained them. He taught a bear to dance for his Jesuit brethren in Québec City. Later he trained a chipmunk and presented it to Louis XIV whose court was fascinated by the little creature. He would also write that the Native People ate grilled unskinned chipmunks.

His breadth of knowledge was amazing and he was interested in Native pharmaceutical lore. The birch sap was drunk by individuals with gallstones and it served to burst the stone which was expelled. Sap also removed blotches from the face and made a fine and beautiful complexion. It also cured mouth ulcers. An excellent syrup was made from maidenhair fern that was refreshing to the chest and sought after in France.

The spruce tree had a variety of uses. Its needle-shaped leaves were used for making beer in the English colonies and had been successfully used in French settlements. Indians used the leaf to make purgative drinks. Spruce sap was used for making salves and was considered very good for wounds and strengthened those with lower back pains. The “sticky liquid form a kind of incense that is not as fragrant as that of Arabia, but nevertheless has some smell of incense.”

He found deer marrow excellent tasting and provided remedies to relax muscles and tendons and to relieve the pain of gout but did not cur gout. Nicolas found beaver “flesh is good to eat, although a little bland and in need of flavouring. It is eaten at any time, including Lent and vigils.” He continued:

“Beaver testicles, whose medical name is castoreum and which the Indian hunters call ouissinak, are excellent for various illnesses. A woman who is tormented by mal de mère feels much better when some of it is burnt under her nose and she smells the bad odour. A pound sells for as much as twenty écus.”

“His drawings of the local plants, animals and Indigenous peoples stand out because, in subject and style, they are very different from the official portraits and religious scenes that dominated art of this period.” The book consists of over 180 illustrations. The codex manuscript is held by the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma and was first published in English in 2011.

These descriptive works were important factors in European intellectual life. During this time the Jesuits published 800 books on mathematics, physics and natural science. Many of these works like those produced about the Lake Superior region brought to the world a vast quantity of empirical data about places well beyond the reach of ordinary travelers.

This is a wonderful survey of the history of Jesuits and French early explorers in the Upper Great Lakes; and timely for us. We just returned to Marquette from a journey through the Gulf of St Lawrence and up the St Lawrence River with visits to Old Quebec (Quebec City), Montreal, Ottawa and Toronto. This piece greatly enhances our learning from this trip. It is a “keeper”.

Thank you Dr. Magnaghi (and Rural Insights) for sharing this history.

Tom Solka

Marquette

Hi, Judge! Hope you are well.

Another fine article Russ. I always look forward to your reports. Thanks, Clyde

As a long time resident of the Upper Peninsula I found this article very interesting. My wife worked for & with Native Americans and so much of their culture has been lost that I’m sure they’d be interested in this & the more in depth reading mentioned. The Native Americans and our distant European ancestors had to be very resourceful people in order to survive.