The Upper Peninsula’s Ukrainian Heritage

The outbreak of Putin-Russia’s war against Ukraine in the spring of 2022 has brought up the question, did Ukrainians settle in the Upper Peninsula?

A study of Ukrainian nationality presents a difficult question to answer, before this study can get underway.1 In the past, Ukraine was not a separate nation but it was broken into provinces of the Russian Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which remained in place until 1918 and the end of World War I.

To further complicate matters, new nations came out of the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire or were expanded – Poland, Union of Soviet Social Republics (USSR), Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and for a while Ukraine. Between 1900 and 1930 when United States census takers talked to people of Ukrainian extraction they would identify themselves as: Little Russians, Ruthenians, Rusyns, Austrian Poles, Russian Poles, Austrians, Galicians, Bukovinians, Russians, Hungarians, Romanians or wherever they thought their original village had ended up in the post-World War I political boundary changes caused by the demise of the Austrio-Hungarian and Russian Empires.

Even people you consider Galicians, part of contemporary western Ukraine, might see themselves as “Transcarpathian Rusyn.” As you study the census data you find individuals giving various birth locations and we do not know their personal ethnic preference. A Galician in 1910 could be a Pole in 1920 and a Czechoslovak in 1930.

As a result this study has put aside its original attempt at identifying Ukrainians but looking at the cultural, fraternal and religious connections to find a working result. If they were a member of the Greek Catholic Union they were more than likely Ukrainian, but not always.

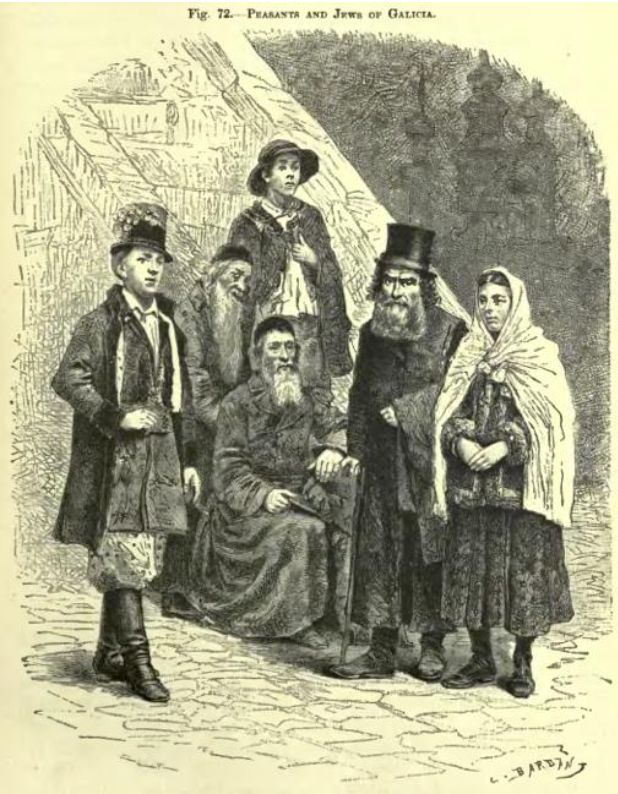

Early 20th century group of Ruthenians or Galicians.

The Greek Catholic or Byzantine Church’s liturgy, language: Old Slavonic unless changed to English, and rules like married clergy follow the Orthodox formula except that they are in union with Rome or Uniate recognizing the pope as the head of the church. This was brought about by the Union of Brest (1596). If a Greek Catholic church were not available these Ukrainians would attend a Catholic church.

Other Ukrainians, primarily in the eastern part of the country belong to the Russian or Eastern Orthodox Church, which after the Great Russian take-over of Ukraine in 1654 successfully Russified the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, but even in Ukraine these lines are blurred. To further complicate matters in 2019 the Ukrainian Orthodox Church was recognized as independent from the patriarchate in Moscow with its own head by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople/Istanbul, spirit leader of the world’s Orthodox churches.

This step was opposed by the Russian Orthodox Church and it broke off relations with the Ecumenical Patriarch. During the war Patriarch Kirill of Moscow has supported Putin in the destruction of Ukraine and its people and gave the war an iconic blessing. You now can see the complicated situation not reported on by the media.

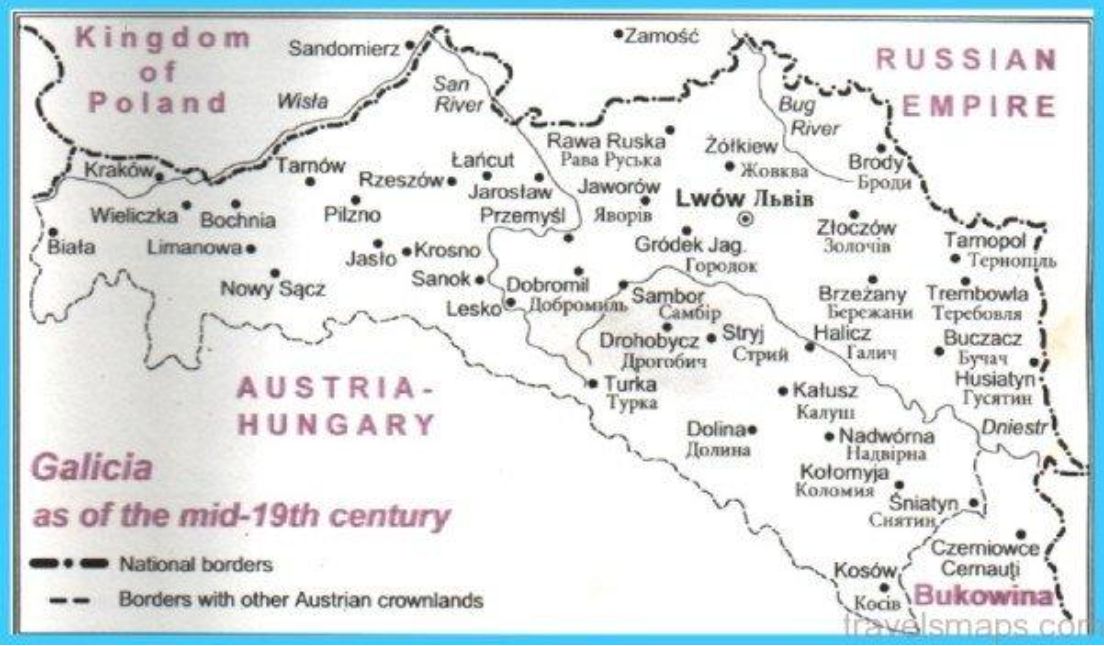

Ukraine until 1991 and the end of the Cold War had a diverse history with numerous rulers. In the late eighteenth century Poland was cut into three parts: Prussian/German Poland in the west; Russian Poland in the east; and Austrian Poland to the south. The south is of particular interest as it consisted of Galicia and Bukovina as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918.

Map: Austro-Hungarian Empire prior to 1918.

The Russian Empire held lands in southeastern Poland bordering Ukraine to the east of L’viv. The names of the city help explain its complicated history as the Germans/Austrians knew it as Lemberg, the Poles as Lovov or Lwów, Russians as Lvov, and the Ukrainians as L’viv. Since they carried varied passports its better identify them by their language, culture, and religious rather than through citizenship.

Today Ukraine, slightly smaller than France, Europe’s largest country is located in southeastern Europe, bordered in the southwest by Moldavia, Romania and Hungary; to the west by Poland and Slovakia; to the north and northeast by Poland and Belarus; and to the south by the Black Sea. It is a nation rich in natural resources, varied climate and fertile soil that makes it one of the most productive regions in the world. Given its exposed position its land has been exploited and its people subjugated, but they have developed and preserve their definitive culture and language.2

L’viv in the early 20th century.

In very few cases the term “Ukrainian” appears but provides little context. A review of the Ironwood, Michigan Ward 1 illustrates the problem of trying to identify Ukrainians. They could be coming from Galicia (6), Tarnów, Poland in Austrian Galicia (4), Russians (5), Russian Poland (33), Hungary Poland (2), Slovakia (79), Spiska Gupa, Slovakia (3). So what follows on the American side of the border is an unclear identification of these people being from Ukraine.3

Peasants and Jews of Galicia

To the north of the UP in the late 1890s Canada was in need of agricultural immigrants to settle the prairie provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta and put out a call for Ukrainian immigrants.4

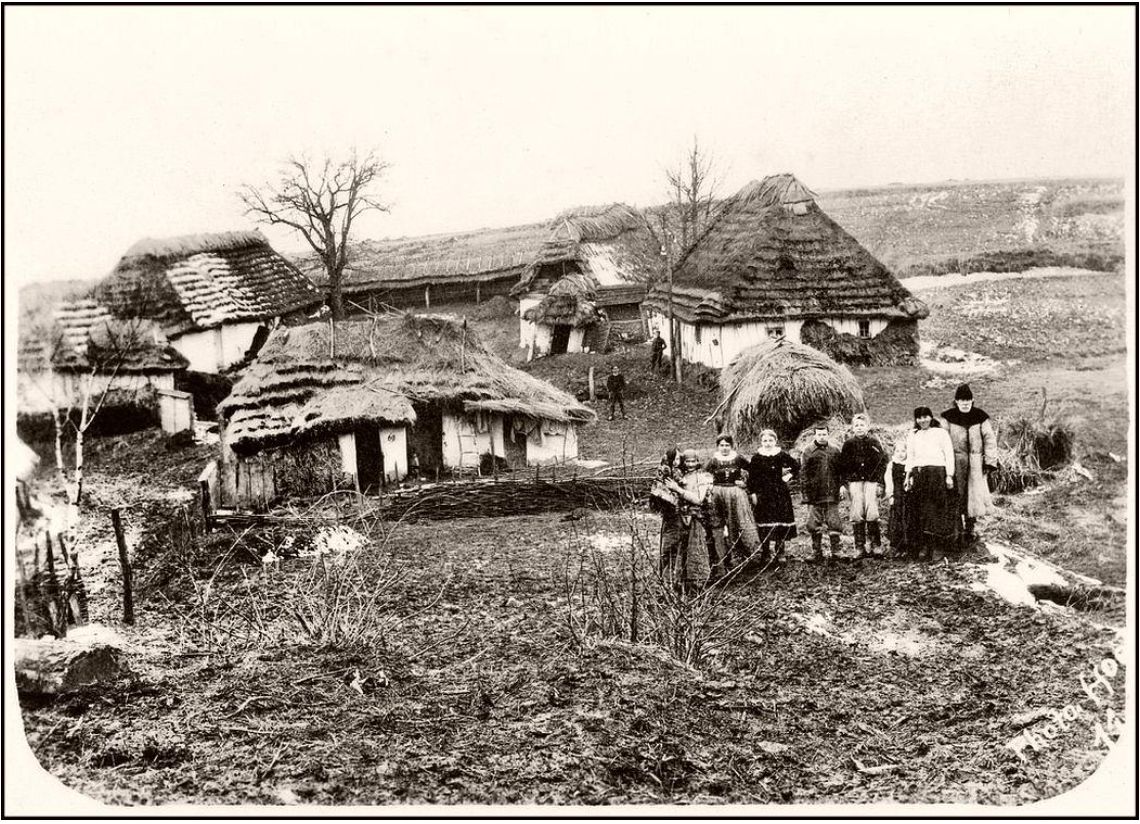

In the Old Country landless peasants faced intolerable land lords and high taxes and opportunity was not even a faint dream for the future. The opportunity to migrate to a land where opportunity lay in front of them if they continued their hard grueling work sent them to Canada. The Ukrainians arrived in a series of waves that continues to this day. The first wave came between 1891 and 1914 from the Austro-Hungarian provinces of Galicia and Bukovina.

Galician farm complex in the early 20th century.

A second wave arrived in the interwar years from Galicia and Volhynia seeking land. This group consisted of laborers, discharged soldiers, political refugees, university professors and farmers. This was followed by displaced persons who had been sent to Germany as forced labor. Now they fled Europe seeking to escape the tyrannical Soviets. They consisted of farmers, skilled workers and professional men and women – scholars, scientists, musicians and artists. They arrived between 1947 and 1952.

A fourth wave began in the 1980s and lasted a decade. With Putin’s war in Ukraine has caused a fifth wave to begin an out-migration. In 1911 there were 3,078 Ukrainians in Ontario and this number rose to 159,880 (27.5%) in Ontario in 1971. On the Canadian side of Lake Superior at Thunder Bay and Sault Ste. Marie the large Ukrainian population maintains their traditions through language schools, dance groups, and maintenance of religious holidays. Attracted to Canada a small numbers Ukrainians crossed the border and entered the Upper Peninsula especially at the Sault.

The first Ukrainians to emigrate of the United States came mainly from the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s provinces of Galicia and Bukovina sometimes known as Ruthenia. They were escaping unemployment, exploitation by large landowners, heavy taxes and poverty. The Ukrainians who first came to Michigan settled in the farming areas around Lansing, Saginaw, Grand Rapids, Muskegon, and Flint. By the mid-1930s some 25,000 to 30,000 Ukrainians lived in Detroit working there and in Flint in the auto industry on the assembly lines, machine shops and steel factories.

At Sault Ste. Marie Ukrainians were close to their countrymen across the St. Mary’s River in Canada. Possibly some of the immigrants from Galicia and Bukovina and the been forced to live with Canadian restrictive regulations during World War I, left Canada and moved south. In 1920 there were over one hundred South Slavs in the Sault. With the demise of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the former subjects clearly identified themselves as: Austrian Polish, Galician Polish, Gulitza Polish, Polish Russians, Russian Yiddish, and Ukraine-Austria (Ruth). These people were more than likely Ukrainians.

The majority of these immigrants were employed at the Northwest Leather Tannery, Soo Woolen Mills, and Union Carbide. Others had a variety of jobs: immigration inspector, canal lock men, and railroad work as section and repair men. The Russian Yiddish listed might have hailed from Odessa home to many Jews and were tailors, hide dealer, dry good merchant, and business commissioner. Restrictive Congressional laws in 1921 and 1924 halted immigration from eastern Europe and further Ukrainian immigration came to an end.5

By the 1930 census the original population remained. At this time the census ended ethnic distinctions and most people were listed as “Polish” or “Czechoslovakians.” In a rare insight the Topi or better known as the Touple family appears, who were from Austria but spoke Ukrainian. Charles was born in 1889 and came to the United States in 1911. By 1930 he had a home at the Sault valued at $700 and he and his twin brother, Frank (1889-1974) operated a farm on the edge of the Sault. Frank had married Clara Handziak in 1925 and they had a 1 ½ year old son Charles (1928-2019).

During the decade Charles left into the unknown and Frank continued to farm but found back-up employment at the leather factory. In the fall of 1939 he was advertising the sale of a ten-month old Guernsey bull and also had hired Mike Drost to work the dairy farm. The family remained at the Sault and Frank continued to work at the leather works into 1950. His son worked there as well and in 1956 was employed by Kincheloe Air Force Base.6 It is interesting to note that over the years of the census the Touples cite “Austria,” then “Poland” and back to “Austria” as their birth nations.

Other identified Ukrainian families can be studied to get a sense of their lives at the Sault and beyond. Wasyl Perucky (1889-1947) arrived in Canada in 1909. He married Anne Jaworska at the Sault in 1914 and then moved to Nova Scotia where three children were born. By 1920 they had returned to Sault Ste. Marie and were joined by Wasyl’s 18-year old sister Anne. They also took in a Ukrainian boarder, Antozek Ihnal who was a laborer at the leather factory. Ukrainian was spoken at home.

Wasyl possessed a strong sense of Ukrainian nationhood. When he registered for the World War I draft in June 1917 he listed the following as to where he was from: town- Strzylki, state- Galicia, and nation- Ukraine and he was a citizen of Austria.7 In the early 1920s the family moved to Waukegan, Illinois where now Wasyl now known as Mike, in 1930 was a laborer in a building material warehouse and ten years later was employed in an asbestos products factory. His death at 58 might have been caused by his recent employment.8

A Ukrainian neighbor was the Wasznske family – headed by John and Anne. They arrived in the United States in 1913 and resided in Brooklyn, New York for a while before they move to the Sault. John was hired as a laborer at Union Carbide and in 1930 John was a yard man in a lumber mill.9

The Melkilka family concludes our review of Ukrainian families. In 1920 Peter was a laborer at the leather factory. His wife raised their two daughters, Stella (age 4) and Mary (age 2). To bring in extra money they cared for four Ukrainian boarders: Charles Drozt (32), John Longkl (32), John Shastkak (24) and Frank Troupe (31) who we have seen earlier. Ukrainian was spoken at home while the men dealt with English while they processed leather.10

Even on the far northern frontier Ukrainians maintained their heritage. The Christmas Eve dinner is the most important family celebration. The table is set beforehand with a handful of hay placed on the table and covered with a linen table cloth. It is symbolic of the hay which the new-born Christ child was laid. The dinner consists of kutya (a grain dish), with borsch (beet soup) followed by various fish dishes – pike, trout and salmon, cabbage rolls, potatoes, mushrooms and other vegetables and fruit and finished with cake, honey, nuts and candies.

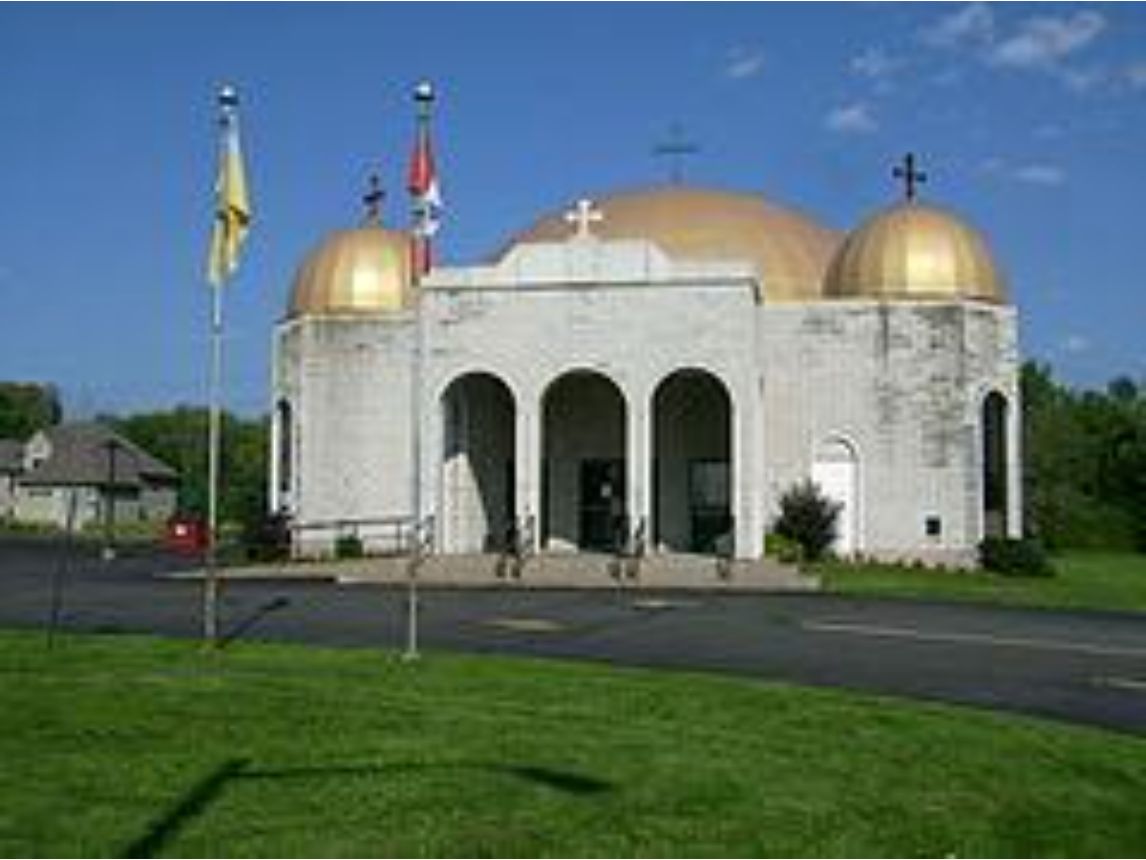

Although the Ukrainian community on the US side of the border was small they were blessed with the larger community across the St. Mary’s River. After 1917 all of these Greek Catholics could easily cross the river by ferry and attend St. Mary Greek Catholic church, visit a social club and thus interact with their countrymen.

St. Mary Ukrainian Catholic Church, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario was dedicated in 1989.

With the expanded development of the iron mines especially on the Gogebic Iron Range after 1890, many Ukrainians migrated north and found work as miners, trammers, laborers in the iron mines or were employed by lumber companies.11 In Ironwood and Bessemer, Michigan on the Gogebic Iron Range in the western Upper Peninsula where there was a large eastern European population – Bohemians, Slovaks, Croatians, Hungarians, Poles, and Ukrainians.

When people were interviewed in the census as opposed to the South Slavs at Sault Ste. Marie they merely stated that they were from Hungarian Slovakia, Slovakia, Russia and Austria Slovakia, but did not highlight their Ukrainian origins or the fact that they spoke Ukrainian among family members. Their census stories provide little information about their lives on the range and interaction with fellow Ukrainians.

In 1891 St. Michael Catholic Church was established for this community of South Slavs. In 1907 Holy Trinity Catholic Church was founded, which gave the above immigrants their own church and left St. Michael to the Poles. The Ukrainian population which numbered possibly some one hundred people never have a population that could maintain its own Greek Catholic church. However visiting priests would visit the area and care for the needs of the Ruthenians.

In April 1934 Rev. Joseph Kovalchik of the United Greek Catholic Church traveled from Minneapolis. He ministered – visiting, preaching and saying Mass at St. Sebastian Catholic Church in Bessemer – to the Ukrainian immigrants who longed for such visits.12 Local Orthodox Ukrainians had the option of attending St. Simon’s Antiochian Orthodox Church in Ironwood, which was established in 1914 or await a visiting priest.13

The Ukrainian-Ruthenian-Slovak communities in Gogebic County developed a number of institutions. Many joined the national mutual beneficial Greek Catholic Society, National Slovak Society and First Catholic Slovak Union of St. Joseph. For young people there was the Roman & Greek Catholic Slovak Gymnastic Union, Sokol of St. Matthew Assembly No, 155. In 1926 athletes from skols in Superior, Duluth, Minneapolis, Iron Mountain, Ashland, and Ironwood held athletic contests in Ironwood.14 This provides us with a sense of the development of these skols which were part of the eastern European culture. Today the Ukrainian presence in Gogebic County is little recognized.

Within the Lake Superior Basin there are three sources of Ukrainian food. Chad Soyou is proprietor of Wilson Creek Café in Powers, Michigan (halfway between Escanaba and Iron Mountain) on Highway US 2 and US 4. Holubchi (cabbage rolls), veraniki (pierogi) and borsch (beet-cabbage soup) are offered. In Thunder Bay there is Baba’s offering a fine array of Ukrainian food. St. Mary’s Ukrainian Church Kitchen has a similar menu that must be ordered in advance or is part of their dining hall menu.

Despite their small numbers and difficulty in identifying them, Ukrainians have been part of the heritage of the Upper Peninsula and have enriched the culture of the region.

Footnotes

1The following are a number of highly useful studies on Ukraine and its neighboring people: Paul R. Magocsi. Carpathian Rus’: A Historical Atlas. Toronto, Ont.: University of Toronto Press, 2017 provide a find collection of maps that are critical to studying this region. Magocsi and Ivan Pop, editors. Encyclopedia of Rusyn History and Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002, 2005; Volodymry Kubijovyc, editor. Ukraine, A Concise Encyclopedia. 2 vols. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1963; Magocsi. “Ukrainians,” in Stephen Thernstrom, editor. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1980.

2“Ukraine,” in James M. Anderson and Iva A. Smith, editors. Ethnic Groups in Michigan. Vol. 2, The Peoples of Michigan. Detroit: Ethnos Press, 1983, p. 274.

3U.S. Federal Census, 1920, Michigan, Gogebic, Ironwood Ward 1, District 0096.

4For a history of Ukrainians in Canada into the early 1960s see: Kubijovyc. Ukraine, II: 1151-1193.

51920 Federal Census, Michigan, Chippewa, Sault Ste. Marie.

61930 Federal Census, Michigan, Chippewa, Sault Ste. Marie, 0014, p. 24; 1940 Census Sault Ste. Marie, 17-16, p. 43; 1950 Census Sault Ste. Marie, 17-24, p. 48; The Evening News 23 September 1939.

7U.S. World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, “Wasyl Perucki,” p. 177.

81920 Census, Michigan, Chippewa, Sault Ste. Marie, 0030, p. 9; 1930 Federal Census, Illinois, Lake, Waukegan, 0075, p. 3; 1940 Census, Waukegan, 49-95, p. 27; 1950 Census, Waukegan, 49-185, p. 62; Leader Telegram (Waukegan, IL) 02 September 1982.

91920 Federal Census, Michigan, Chippewa, Sault Ste. Marie, 0030, pp. 9-10.

101920 Federal Census, Michigan, Chippewa, Sault Ste. Marie, 0030, p. 9.

11Anderson and Smith. Ethnic Groups, pp. 275-77.

12Ironwood Daily Globe 12 April 1934.

13Tom Stankard. “St. Simon Orthodox Church Celebrates 100th Anniversary,” Ironwood Daily Globe 28 September 2015.

14Ironwood Daily Globe 03 July 1926; 11 May 1929; 30 March 1936; 01 April 1936; 26 October 1946.

The best discussion of the history of Ukraine in the European context and the Upper Peninsula context that I’ve seen. This deserves wide attention.

Thank you Professor Magnaghi and Rural Insights.

Thank you for researching and writing this piece. You’ve helped clarify my family heritage and I know that I fit into the broader Ukrainian definition you describe. My maternal “Polish” grandfather was listed as being Galacian on immigration records. Now we know why! My paternal grandfather was Austrian/Tyrol and the shifting borders always upset him. Both took entry level mining jobs, saved to buy land in the UP and became successful and enduring farmers. Their now substantial land holdings in Dickinson county is still owned by family members, where crops are raised and put for sale. Neither maintains the dairy herd they were once known for.

My husband has put effort into researching our ancestry and this well written article has added dimension to it.

Thank you,

My paternal grandfather was born in 1879 in what is now known as Zhitomir, Ukraine. In the US census it is noted that he emigrated from Russia. His journey and that of his family from northeastern Poland to Ukraine in 1854 is chronicled in “The Prussians from Russia” by Michael J. Anuta. This article brought a smile to my face as the description of the Upper Peninsula Ukrainian settlers’ heritage is as convoluted as my own! Thank you for the great article.

Russell, I very much appreciated the efforts you made to include the ethnic history of the Ukrainians in the UP.

My father Walter Kilarski, came from Poland in 1914, two weeks before Franz Ferdinand was assassinated. His father was a minor officer in the Hapsburg army and, I think, saw the handwriting on the wall. He fled Galicia, the area around Tarnow, a few months earlier and had settled in Saginaw. I also appreciate you interest in Ethnic history and the efforts you make to demonstrate its importance still.

Good article. Holy Trinity Church in Ironwood was formed by Slovaks, Croatians, Slovenians, Hungarians, and Czechs who split from their fellow Slavs [Poles] at St. Michael’s parish in Ironwood c. 1907. The cornerstone of Holy Trinity identified it as a “Slavish Church,” a term commonly used by Slovaks to describe themselves before WWI, when Slovakia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

After the formation of Holy Trinity, St. Michael’s became mostly Polish, with some Lithuanian parishioners. Both parishes closed in 1986 and consolidated with St. Ambrose, the third Catholic parish in Ironwood. The new congregation became known as Our Lady of Peace, perhaps as an attempt to heal the divisions in the new parish. The closure of the two parishes had caused great resentment among the parishioners of Holy Trinity and St Michael’s. A number of the parishioners from the two closed Churches refused to join the consolidated congregation and joined St Mary’s parish in neighboring Hurley, WI. Both Holy Trinity and St Michael’s were demolished in 1987. With their demolition, along with the destruction of the Swede-Finn Church [Grace Lutheran], Ironwood lost much of its Eastern European-like skyline.