The Central Upper Peninsula’s Native Americans – Part One

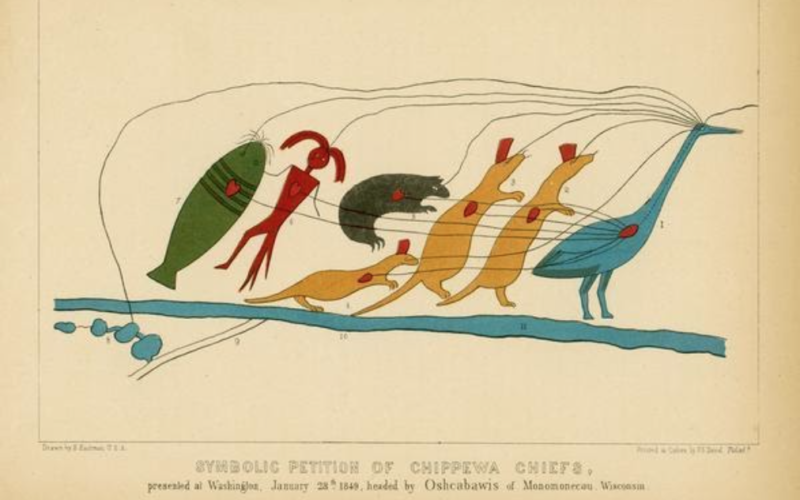

Photo: Symbolic Petition of the Chippewa Chiefs, 1849 Contemporary elders say that the lines from the hearts and eyes of the Catfish, Man-fish, Bear, and the three Martens to the heart and eye of the Crane signify that all the headmen shared the same views. The last line, going out from the Crane’s eye, indicated that the entire group had authorized Chief Buffalo (Crane Clan) to speak to President Fillmore on their behalf.

“Rural Voices” shares cultural, educational, economic and artistic views of people who have lived and thrived in the Upper Peninsula. Each of our authors in Rural Voices may be living here in the U.P. or living someplace around the globe, but the U.P. is an important part of who they are and what their beliefs and values are today. Rural Voices wants to share the voices of our neighbors and friends about life and experiences in the UP.

The following is the first of a three-part series we are running, featuring local historian Russell Magnaghi’s piece “The Central Upper Peninsula’s Native Americans.” Part Two will be featured next Friday.

Prehistoric Ojibwe Communities

Throughout history, Native Americans: Ojibwa, Odawa, Potawatomi, collectively known as Anishinabe, have inhabited the Upper Peninsula, along with the Wenet/Huron who settled here for a short period.

The story of the Ojibwe communities in the Lake Superior basin goes back to the Ojibwe living in northeast North American, probably in the vicinity of the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. Seeking to retain their traditional life, they began migrating westward–possibly around 1500.

They entered the Lake Superior basin and found manoomin (wild rice) or “the Food that Grows on water” that prophecy had told them to seek.

The Ojibwe divided into two groups with one group moving along the north shore of Lake Superior and the other along the south shore. The latter group was the large and was composed primarily of the families of the Crane, Bear, Catfish/Sucker, Loon, and the Marten and Moose clans.1

Their story is intricately linked with the arrival and movement of French voyageurs. The French provided them with trade goods – especially guns – which allowed them to dominate rivals and eventually brought them into conflict with the Dakota (Sioux) in Minnesota and the Sauk-Fox to the south in northern Wisconsin.

By 1680, the major Ojibwe communities were at Sault Sainte Marie, Grand Island, L’Anse-Keweenaw, and ultimately at Madeline Island in Chequamegon Bay in northern Wisconsin. The latter location was known as Mooningwanekaaning (Place of the golden breasted woodpecker) and became known as a powerful spiritual area.

In this process, various groups broke off and formed smaller communities at Bay de Noc (Escanaba), Watermeet (Lac Vieux Desert) and Mole Lake and Lac du Flambeau to name a few.

Symbolic Petition of the Chippewa Chiefs, 1849

Contemporary elders say that the lines from the hearts and eyes of the Catfish, Man-fish, Bear, and the three Martens to the heart and eye of the Crane signify that all the headmen shared the same views.

The last line, going out from the Crane’s eye, indicated that the entire group had authorized Chief Buffalo (Crane Clan) to speak to President Fillmore on their behalf. View the original source document: WHI 1871

Although Marquette was not a large settlement site such as Sault Ste. Marie, it does have a history of place and Native People.

Historically, Native Americans can be traced back to 8,500-7,000 BCE (Before Common Era) inhabiting a site in the Silver Lake Basin. At the Menard site up the Carp River from its mouth, Native Americans worked a large quartzite quarry during the late Archaic period (3,500-500 BCE).

At the same time Native Americans occupied a large campsite or village on Presque Isle. Native Americans had connections with this area back to 3,000-7,000 years ago. Copper artifacts were in use with preferred quartzite. This was considered one of the largest prehistoric occupations in Marquette County.2

The arrival of Europeans in the Americas brought technological change to Native Americans. Suddenly iron tools, pots and other devices became available to them.

Soon after Columbus’ arrival in 1492, he found a Native American pushing ahead of Columbus across the Caribbean ready to trade a collection of sharp broken glass with unbelievable cutting properties. The major source for seventeenth century trade goods for the Upper Peninsula was Québec City–established as a fur trading post in 1608 by its founder Samuel de Champlain.

An inveterate explorer, he started the process of exploring lands to the west and soon discovered the Ottawa River route to the west. He had sent Étienne Brûlé to live among the Wendat and learn their language, geographical knowledge and culture.

By 1621, Brûlé had made a winding journey that led him and an associate Grenolle to Sault Ste. Marie at the junction of Lakes Superior and Huron. The Franciscan Récollet missionary, Gabriel Sagard has left us the only account of Brûlé discovery: “The interpreter Bruslé [sic] with several Savages assured us that beyond the Freshwater Sea [Lake Huron] there was another very large lake which empties into it by a waterfall, which has been called ‘Saut de Gaston’ [Gaston Falls, i.e. Sault Ste. Marie].3

Once the French arrived in the St. Lawrence Valley, Native People from far and wide saw the immediate value of French manufactured goods and what they had for trade – furs.

Documented knowledge of the early movement of the Native or the French traders is not available. Neither kept records, and the French did not want data of their markets in the West to be known. Fortunately, archaeological evidence tells us that this trade had begun at an early date.

As the years pass, archaeologists like John B. Anderton are adding to our knowledge of Native American life in the Marquette vicinity. The Goose Lake Outlet #3 site inland from the city of Marquette was discovered in 2011 and investigated for two years. It is a site that provides insights into this early trade.

Dating from the 1630s, a proto-historical period, the winter camp shows us intercultural interaction and exchange. At this site European trade goods have been found prior to the establishment of French fur trade posts at the Straits of Mackinac.

The winter camp was home to a group of Anishnaabee.5 During the summer months these Native People probably lived along the shore of Lake Superior and subsisted on a heavy fish diet, which some authorities say was as high as 75 percent.

During the winter they relied on boiled, roasted or raw moose. They also had food caches on site where maple sugar, dried berries especially blueberries, and wild rice wrapped in birch bark was buried for future use.

Through trade they obtained a variety of valued manufactured goods. The fragments of copper kettles indicate a move from hot stone cooking in birch bark container. Later Jesuit accounts tell of Native People communally cooking in kettles. Also found on the site were iron knives, iron scissors, and sewing needle, all items essential for clothing making.

A leather belt with a copper rivet was also found that could have been used as a tumpline for carrying goods using your head. Also found on site were robin egg blue beads that were sewed onto their clothing. These beads might have fallen off the clothes onto the snow and “lost.” They were made in Venice, Italy, the source for most beads of this era.

Five Jesuit rings were also found at the campsite. The origin of these rings is a mystery because Jesuit missionaries did not enter the Basin until 1660 when René Ménard, S.J. traveled along the shoreline of Lake Superior enroute to establish a mission among the Odawa and Wendat at La Pointe. The St. Mary mission was established at Sault Ste. Marie in 1668. The bundle of rings might have been carried as jewelry or by Native converts from the east.

Colonial Era, 1659-1796

The pre-historic period blends in with the French colonial era beginning in 1659-1660 when two Frenchmen, Pierre Esprit Radisson and his brother-in-law, Médard des Groseilliers visited the Lake Superior Basin. Radisson left a partial record of their visit. They traveled passed Marquette and wintered on the shore.

At a point west of the city they gave a variety of goods to the Anishnaabee: kettle, two tomahawks, six knives, 22 awls, 50 needles, 2 scrapers, ivory and wooden combs, 6 tin looking glasses, brass rings, small bells and beads in diverse colors.6 They also gave goods to the Menominee, but there is no further information about gift distribution. However these goods attracted Native interest and were items that greatly enhanced their lives.

Soon after, the French presence in the Basin grew and developed. The fur trading post, Fort Buade was established in 1681 at St. Ignace and later Fort Michilimackinac was established in 1715 at Mackinaw City on the south side of the Straits.

During this era explorers, traders and missionaries passed in canoes in front of Marquette but few landed. The route traversed the front of the bay from Shot Point to Little Presque Isle. This was done to avoid the detour of traveling into Marquette harbor, which would add several miles to their trip and there was no reason for landing at the future site of Marquette.

Remaining in the Lake Superior Basin during the long and harsh winters was to be avoided. The Bay de Noc-Escanaba today is known as the “banana belt.” The Lake Superior shore receives 200+ inches of snow while Escanaba averages fifty inches.

As a result, Native People traveled down the Carp River trail, which followed a land trail and then along the Escanaba River once they reached the Forks (modern Gwinn). Several days later they were in Flat Rock/modern Escanaba in a more hospitable climate and environment having passed many Anishnaabee camps along their route. There were other winter hunting camps in the interior of the county and trails from Lake Superior were traveled to reach them.7

As events distant from Marquette developed, local Native Americans heard about them but we have no recorded of their involvement. The fur posts at the Straits provided them with trade goods. They learned of Upper Peninsula Indians joining the French at Québec City in 1760 when the British defeated the French and their Native allies and took control of the Great Lakes region.

A certain fear struck them since the British had treated Native People poorly and this was well known. Possibly the smallpox epidemic spread by the British reached the central Upper Peninsula and made local native American fear the future.8

The British established themselves at Fort Michilimackinac, but concerns by Native People led to the Pontiac Uprising at the fort in 1763. Fortunately, peace was quickly restored.9

The fur trade–the basis of the Lake Superior economy–continued, wars with the Fox to the south and Lakota to the west attracted Ojibwe to join partisans and fight. The American Revolution was heard about through Native and British sources.

In 1780, the events probably hit home when in preparation for an attack on St. Louis, seven hundred miles to the south, Commander Patrick Sinclair sent Jean-Baptiste Cadotte from Fort Michilimackinac to recruit Ojibwe along the southern shore of Lake Superior. Their attack on the Spanish settlement in May was unsuccessful.

However, the British promoted the idea that the American occupation of the Lake Superior Basin would bring farmers and Indians would lose their lands. Rumors were rampant.

Early American Period, Post-1796

When the Americans arrived in 1796, life for the Marquette community remained basically untouched as the fur trade continued. The closest major Native settlement was at L’Anse where the North West Company and the American Fur Company had posts. However the spread of non-traditional farming among Upper Peninsula Native People reached Marquette.

By 1809, above the mouth of the Dead River, Native Americans were cultivating a little corn–although the soil was thin and poor for the best farming. At the same time, Louis Nolan, a metis, and two Ojibwe traveled from the Carp River to the Menominee River.

During these years, the government factory or trading posts could have attracted have attracted local Ojibwe seeking an outlet for their low quality furs. However, they would travel to St. Joseph Island in the St. Mary’s River to trade with the British for quality goods and bargain deals.

In the build-up to the War of 1812, local Native Americans would have heard of La Maigouis/The Trout, a disciple of Tecumseh who entered the Basin. He called for Native People to return to their traditional ways and avoid American intrusions into their lives. Possibly some of the local people joined the British at Fort Mackinac in the struggle against the Americans in the summer of 1812.10

The “Central Upper Peninsula’s Native Americans” three-part series will continue with Part 2 next Friday.

References:

1Mattie Harper. “On the Shores of the ‘Great Water’: The Ojibwe People’s Migration to Gichigaming,” The Growler (May 29, 2018).

2Marla Buckmaster. “The First Yoopers, The Archaeological Evidence,” in Russell M. Magnaghi and Michael T. Marsden, editors. A Sense of Place, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Marquette: Northern Michigan University Press, 1997, pp. 1-4; Dr. Scott Demel, archaeologist at Northern Michigan University is working this site as of 2019; James R. Paquette. The Find of a Thousand Lifetimes: The Story of the Gorto Site Discovery. Bloomington, Ind.: Author House, 2005.

3James H. Cranston. Étienne de Brûlé: Immortal Scoundrel. Toronto: The Ryerson Press, 1949; Consul W. Butterfield. History of Brûlé’s Discoveries and Explorations, 1610-1626. Cleveland, Ohio: The Helman-Taylor Company, 1898; Gabriel Sagard. The Long Journey to the Country of the Hurons. George Wrong and H. Langton, editors. Toronto: Publications of the Champlain Society, 1939, pp. 242, 263, 265; Jeanne K. Hanson. “The Extraordinary Life of Étienne Brûlé: Breaking Trail t the Big Lake in the 17th Century.” Lake Superior Magazine (June 1, 2014) on-line.

4The only available archaeological study: John B. Anderton. “Native American Camp in Marquette County, Michigan.” Upper Country, Journal of the Lake Superior Region (2019). On-line.

5There has been some discussion that the inhabitants might have been Wendat/Huron. Originally living in the vicinity of Georgian Bay they had access to trade goods and could have been the Native traders reaching this site. However they were attacked by the Iroquois in New York state during the Beaver Wars. They fled westward to La Pointe (modern Ashland, Wisconsin) and eventually in the early 1670s re-settled at the Straits of Mackinac.

6Pierre-Esprit Radisson. Voyages of Pierre-Esprit Radisson. Introduction by Gideon D. Scull. Boston: Prince Society, 1885, pp. 189-190, 200-201; Germaine Waekentin, editor. Pierre-Esprit Radisson: The Collected Writings. Vol. 1 “The Voyages.” Montréal, Québ.: McGill & Queen’s Universities, 2012.

7Russell M. Magnaghi. “On the Move: Traveling the Carp River Trail.” Michigan History (January-February 2020), 50-55; [Interview with George Madosh], Terri Hughes-Lazzell. “Overlooked, Chief’s Great-Grandson Holds onto History,” Mining Journal 04-25-1991.

8Edward Jacker. “The Small-Pox among the Indians at Fort Michilimackinac in 1757,” United States Catholic Historical Magazine vol. 1 (1887): 101-103.

9For an overview of the British era see: Magnaghi. Native American of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula: A Chronology to 1900. Marquette: Northern Michigan University Center for Upper Peninsula Studies, 2009, pp. 56-70.

10Ibid., pp. 75-78.

Russell:

Next Wednesday Eric Drake is doing a presentation via the Marquette Historical Center

on the logging and Native Americans involved in central U.P. The town of Nahma was

mentioned in the write up in the Mining Journal today (Friday). I am trying to get

information on how to steam that as I live in western Wisconsin….but I grew up and went

to school in Nahma. You might also like to know that Bud Sargent (Mining Journal Editor)

was born and raised in Nahma. I suspect that perhaps part two of your presentation on

“Rural Insights”. Nahma is the Indian term for Sturgeon….the Sturgeon RIver empties into

Big Bay de Noc in the Village of Nahma. I suspect you knew all of that ! Thank you for the fine read

in par one. dghartman@centurytel.net

who is “he” in this sentence? Mesnard, from 3 paragraphs earlier?

“Soon after Columbus’ arrival in 1492, he found a Native American pushing ahead of Columbus across the Caribbean ready to trade a collection of sharp broken glass with unbelievable cutting properties.”

You forgot to mention the last 8,000 years presence of the Nooke people in the Great Lakes since the recession of the glacial made the environment more stable. The story of the U.P. is still left unwritten.

The Nooke were present here for thousands of years, or their ancestors. Very important to tell truth.

commentors: when you mention the “Nooke”, could this also be the “bay de noc” who resided around Nahma area?