Exploring the Latest Census Bureau Estimates of UP Population Change from 2020 to 2022

For the past several years, Rural Insights has published a number of articles focused on population change in the UP. These articles found that the region’s only source of short-term population growth is migration, as its number of deaths exceeds its number of births.

Why is this such an important issue? An area’s population change is a critical indicator of a community’s socio-economic well-being. Population decline often means a drop in an area’s tax base, while falling school enrollment can ultimately lead to school closures, school district consolidation, and a drop in the number of school employees.

The absence of a local school makes an area less attractive for young families with children, so they leave in turn. These changes lead to a downward economic spiral. A loss of local spending power negatively impacts businesses, while falling or stagnant local tax revenues means city and county governments struggle to maintain services.

This process has repeatedly played out across the UP over the past 100 years as cities and towns have shrunk or disappeared altogether.

Population growth brings different challenges: a rise in the demand for goods and services, and depending upon the size and duration of the population gain, a boost to employment as new businesses are created or expanded. A shortage of housing may also lead to new home construction while new resource demands negatively impact the environment; just as Joni Mitchell once warned, paradise is paved over for more parking.

In short, population matters. It is central to thinking about the future of the UP: will it become a place young people leave in search of more job opportunities? Or a bedroom community for part-time residents? Or might there be a third option, balancing economic and population growth while preserving the environment?

The UP’s population has been in decline for several decades due to a falling birth rate, rising mortality due to an aging population, and the failure of in-migration to offset the difference between births and deaths.

This article uses the US Census Bureau’s latest population estimates for 2022, based on births, deaths, and migration at the county level, to provide an update on the region’s most recent population changes, and suggests what may be contributing to population gains.

2022 Population Estimates

Between 2020 and 2022, Michigan’s population declined by about 35,000, with the biggest loss (32,000) associated with Wayne County, in the Detroit metro area, and the largest gain (4,000) occurring in Ottawa County, on the Lake Michigan shoreline. The state’s 0.35 percent decline contrasts with an estimated population gain of less than 0.1 percent for the UP.

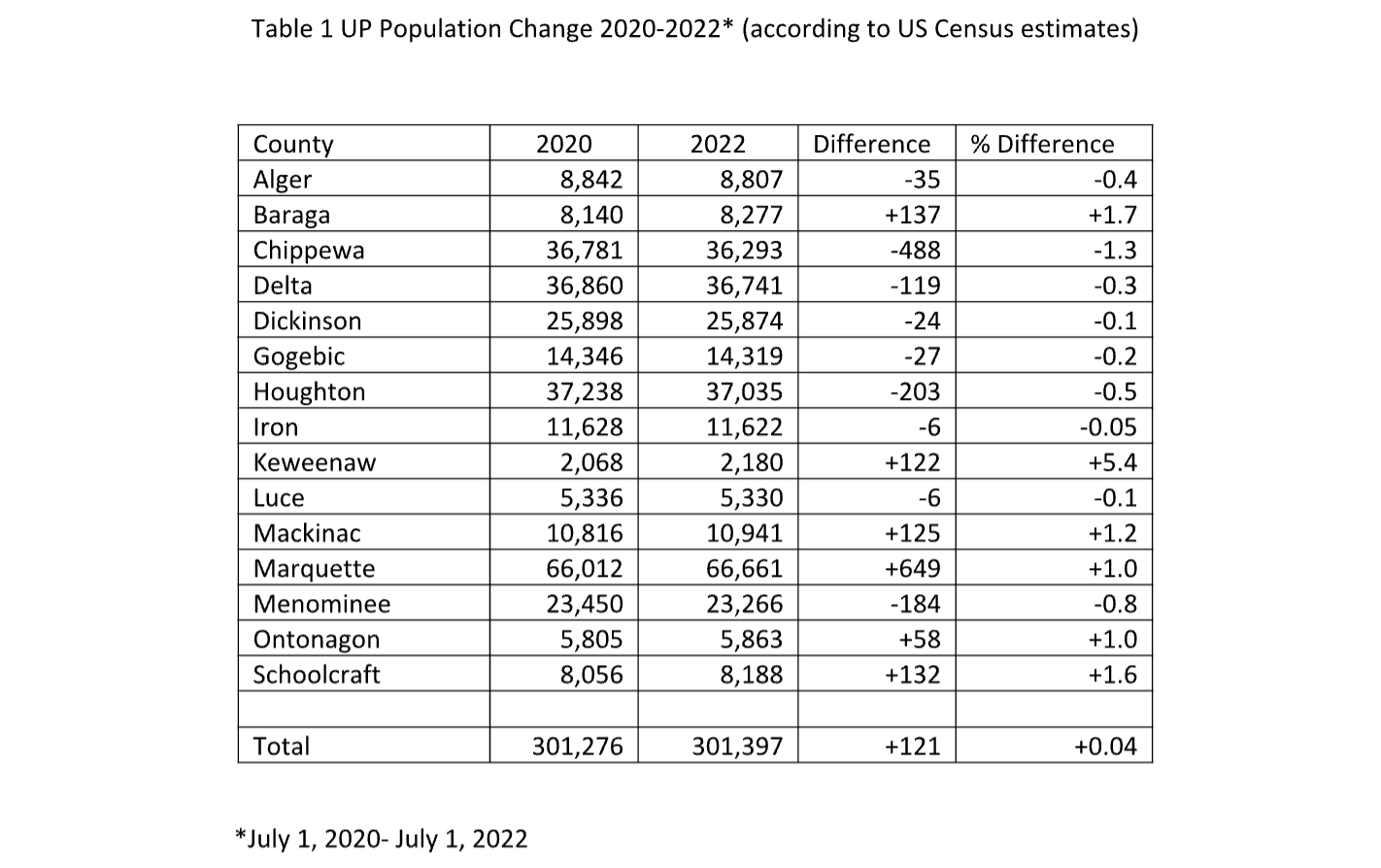

Most UP counties lost population, however six actually grew: Baraga, Keweenaw, Mackinac, Marquette, Ontonagon and Schoolcraft (Table 1). Keweenaw, with just over 2,000 persons, had the state’s largest percentage population gain at 5.4%, or 112 persons. Marquette County has the UP’s biggest increase at 649 persons. Interestingly, Houghton County, the only UP county to have gained population between 2010 and 2020, is projected to have lost 203 persons.

Retirees and Remote Workers

In the past, job availability has been a major factor behind population movements. Major job losses or the absence of jobs in a community would lead to out-migration, while the creation of new jobs, such as in a new mine or lumber mill, would lead to in-migration.

But in Marquette County, according to the US Bureau of Labor, the average annual number of people employed in the private sector fell between 2019 and 2022, from 21,450 to 21,059 (2020 data were not used due to the Covid-related layoffs). So, despite shrinking employment, the county’s population grew.

This apparent anomaly can be explained by an influx of remote workers and or retirees, since neither group would be counted in local employment statistics. Data from the Social Security Administration provide partial support for the retiree explanation as the number of Marquette County retiree social security recipients increased by 2 percent between 2019 and 2021 (2022 data are not yet available), surpassing the state’s 0.7 increase.

Anecdotal observations by local realtors and contractors indicate an influx of home buyers to the Marquette area from the Detroit and Chicago areas. Developers clearly have empty nesters and retirees in mind when they develop lakeshore condominium properties. Away from the lake in Marquette Township, Langford Drive has lots listed at $120,000 for a quarter acre and appears targeted at out of towners.

Ontonagon and Schoolcraft counties provide further evidence of a decoupling between employment gains and population growth. However, given the size of their respective population gains (+58 and +132), along with their employment losses (-15 and -90 respectively) it is important to not read too much into this apparent anomaly.

Baraga, Keweenaw and Mackinac counties provide indirect evidence linking private sector employment increases (+28, +18 and +135 respectively) with their population gains. Migration theory asserts that most moves occur over short distances, so one possible explanation for some of the population growth in Ontonagon, Baraga and Keweenaw is out-migration from Houghton, its adjacent neighbor, which lost population.

Future Population Growth

Marquette County’s recent population growth appears linked to an influx of remote workers and retirees. And as more Americans consider the effects of climate change in their migration decision-making, the area might see more newcomers.

Local jurisdictions welcome the construction of new homes, the increase in taxes and economic activity that accompanies the new arrivals. However, the median household income for Marquette County is $58,000, putting most new homes out of range for the majority of locals.

New home construction will remind local residents of the widening gap between those who can afford a home and those who cannot, unless policy-makers can find a way to increase the availability of affordable housing. At the same time, any increase in development is likely to further rural sprawl, with its environmental costs of habitat loss and increased resource usage.

It is worth remembering Joni Mitchell again: ‘Don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you got ’til it’s gone?’

This apparent anomaly can be explained by an influx of remote workers and or retirees, since neither group would be counted in local employment statistics.” This statement really makes these numbers suspect. I have seen different projections which indicate Gogebic County (and the City of Ironwood) have actually gained some folks over this time period. MANY young folks have moved here that work remotely. If they are really not counted, then these numbers (and deductions from them) have less validity.

I believe the article is saying the remote workers ARE counted in population data, but NOT counted in local employment data. So the population numbers would be considered accurate, but the anomaly exists between our expectation that population increases have historically meant more local jobs (but that changes with remote workers and retirees increasing the population).

I believe we need to get more immigrants to fill some of these jobs. They have proven themselves, and they do good things contrary to what some people say, they do hard workers.

Thanks, Michael and John, for your insight into population changes in the UP. A 2 year period may be insufficient to draw conclusions, but I am not a demographer. It would be great to see a detailed study done of who lives where in the UP, how long they have lived there, where they came from, what is their occupation, or if retired, unemployed, disabled, etc., whether they own or rent, their income [and debt] level, educational and marital status, whether they plan to remain living in the UP, etc. There is a lot of anecdotal evidence that the population of many UP communities is changing. What are the reasons? The residual effects of the collapse of iron and copper mining? The very large percentage of the elderly population [Ontonagon County, for example, is the 7th oldest county in America, according to the 2020 US census, with 35.9% of the population being 65 and over. Keweenaw County is the 10th oldest county in the US.], the relatively, often quite cheap real estate values, the growth of Air B&Bs, etc. etc. Also other demographic factors, such as the presence of a college/university in a community, population growth among Native Americans, particularly on reservations and its effect on a county’s population, the effect of remote workers moving into the region and whether this is permanent or temporary, the location and effect of hospitals, etc. Perhaps what is needed is an economic summit of the Lake Superior Region, bringing together ALL the stakeholders. In any event, I look forward to reading the results of more of your research into the demographics of our region. Continue!

Interesting stuff and I was thinking about population increase and decrease in the UP. I feel that in regards to Keewenaw county there may be many more people due to the number of people who have cottages/ camps et and only use them for part of the year. It would be interesting to see who actually holds the council /municipal jobs in the Keewenaw, where they came from etc. A few years ago there seemed to be a number of people who moved there in the mid 2000’s who were from Indiana, Texas, Ohio etc. I always thought it better to employ local people for these positions as they have usually a more significant “Buy in” and understanding of local areas and can make for a better community, social connections and the building of trust and social capital.