Charging Into the Future: Can EVs Thrive in the UP?

Tristin Smith is a research assistant at the University of Michigan’s Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy (CLOSUP), where she works on the Center’s “Close Up on the UP” project. She is a third-year in the School of Information majoring in Information Analysis and minoring in Digital Studies and is part of the U.P. Scholars Program. Tristin is interested in researching the intersection between technology and education.

“CLOSEUP on the UP” is a collaboration between CLOSUP, U-M’s UP Scholars Program, and Rural Insights.

It’s safe to say, spotting an electric vehicle (EV) in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula used to be about as rare as encountering a moose. Having lived there for 18 years without ever seeing a moose, I know firsthand how uncommon they are in the UP – though your experience may differ. Similarly, an EV sighting in the UP still might catch you off guard. It’s something we (Yoopers) don’t often expect. Those who have driven EVs in the UP are likely all too familiar with the challenges that accompany this.

Although electric vehicle momentum was building in recent years, 2025 has not proven to be a breakthrough year for EVs in Michigan.

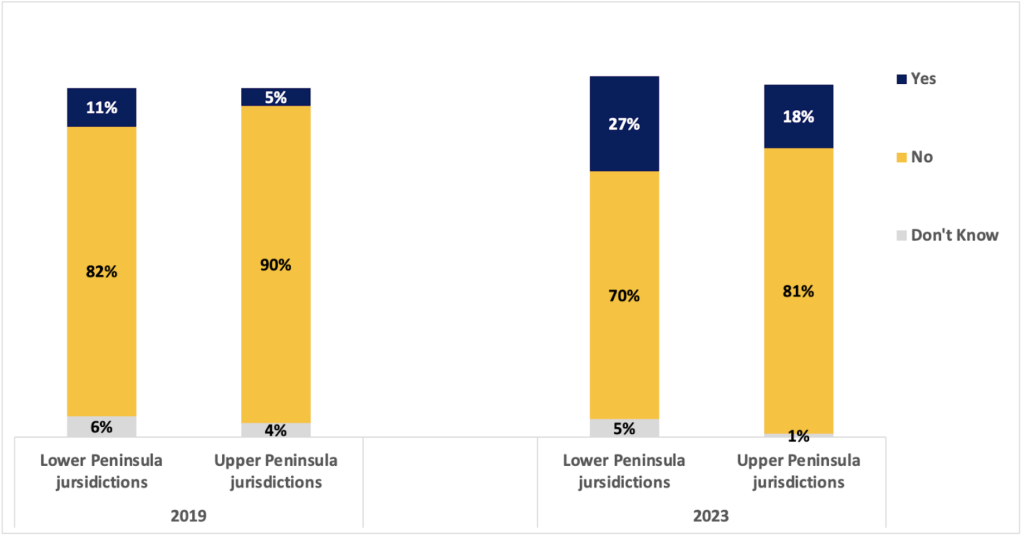

In both 2019 and 2023, the University of Michigan’s Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy (CLOSUP) conducted statewide surveys of all Michigan counties, cities, villages, and townships on energy issues, including a set of questions about local policies on electric vehicles. One such question asked was, “Are there any publicly-accessible EV charging stations in your jurisdiction?” The responses revealed a gap between the UP and Lower Peninsula communities. In 2023, 18% of local UP officials said their community does have EV charging, up from 5% in 2019. In comparison, 27% of respondents in the LP said they have local charging stations.

While the lack of EV charging stations is an issue statewide, it is apparent that this issue can be more pronounced in the UP, where long travel distances exacerbate the problem. Limited EV chargers may deter EV owners from traveling through or within the UP. In turn, decreased accessibility has the potential to restrict growth of the tourist economy in the UP.

Figure 1: Percent of Michigan local leaders who report that there are EV charging stations in their community, 2019 vs 2023, by region

Local Government Efforts

As reported by CLOSUP, only 13% of Michigan’s local government officials report having considered or adopted any local EV policies to fund or incentivize the use of EVs. However, this is double the percentage who said they had considered or adopted such policies four years earlier. While this is a slow adjustment, it demonstrates the attitudes towards EVs are positively growing in Michigan, this is a slow adjustment. However, in the UP, where EV adoption lags, the adjustment is even slower. In 2023, 39% of UP local government officials said that planning for EV infrastructure is “not at all relevant” for their jurisdiction, compared to only 27% of LP government officials. The combined lack of charging stations and slow pace of policy development regarding EVs creates a feedback loop that discourages EV presence in the UP. As the popularity of EVs grows, so does the importance of integrating EVs into the UP’s infrastructure.

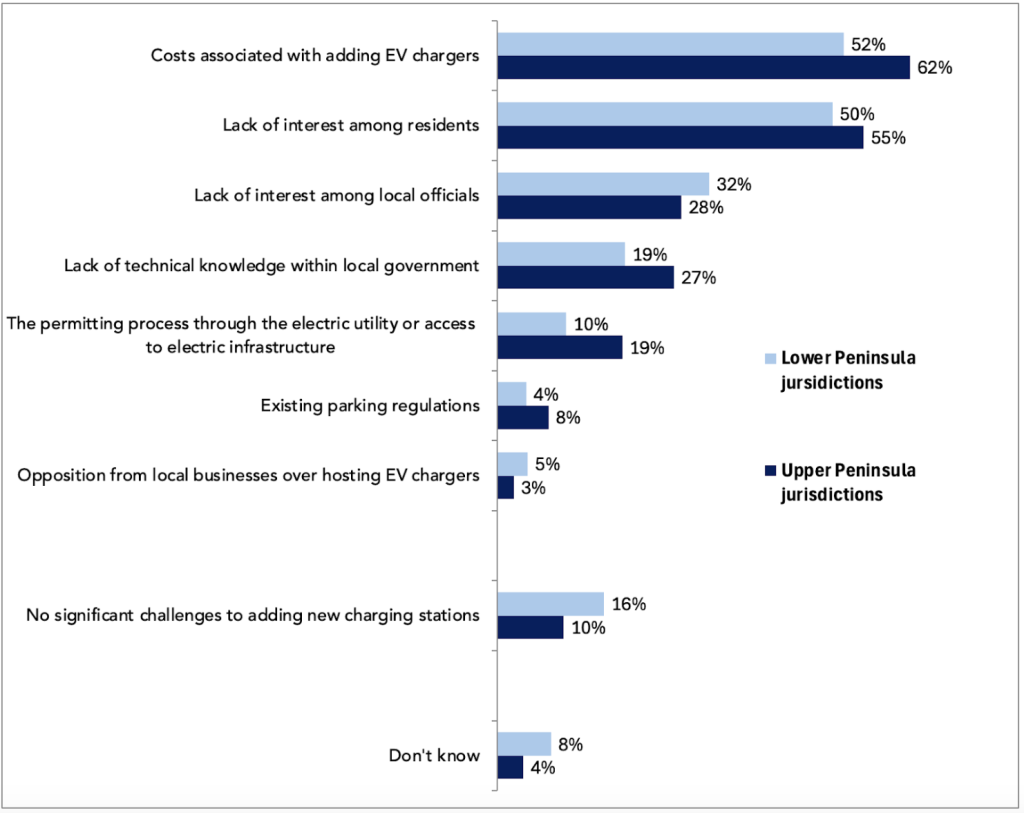

As shown below in Figure 2, local government officers deal with a combination of challenges in regard to incorporating EVs into their respective communities. Additionally, 62% of leaders in the U.P. and 52% in the LP cited the costs associated with installing EV chargers as a significant challenge for public EV station development. But even though UP officials think EVs aren’t relevant, the mindset among UP local leaders themselves compared to LP considering the lack of interest among local officials is 28 percentage points in the UP versus 32 percentage points in the LP, shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Percent of jurisdictions reporting challenges to adding new publicly-accessible EV charging stations in their jurisdiction, by region

Beyond Chargers: Cost & Climate Challenges

Charging infrastructure is only part of this story. An additional barrier to EV adoption is the high cost of the vehicles themselves. This is prominently seen in rural areas such as the UP, where incomes are often lower than the state average. The median income in the UP is $51,950 compared to the LPs median of $63,202 (Michigan poverty and well-being map: Upper Peninsula, 2024). According to Bridge Michigan, in Washtenaw County residents are three times more likely to drive an EV compared to the average Michigander. Out of the 366,00 residents in the county, there are 4,380 registered EVs. This is approximately 17 times as many as the amount of EVs in the UP. Additionally, the median household average in Washtenaw County is $84,000, or about $17,000 higher than the state average. In comparison to Marquette County in the UP, the highest median income is $63,000 and has only 61 registered EVs. For context, Marquette County has about 24,000 residents out of the UP’s total of about 311,000 residents. Even if charging stations become more available, affordability still remains a challenge.

Another significant challenge EVs face in the UP is the weather. Winter maintenance is notoriously demanding, and while EV charging stations could theoretically be installed throughout the region, maintaining them during the harsh winter months is not practical. The area would require regular plowing, salting, and additional measures to ensure the charging stations remain operational in freezing temperatures.

Moreover, EV functionality in extreme climates further complicates their adoption in the UP. EVs rely on lithium-ion batteries, which perform optimally between 32 degrees Fahrenheit and 140 degrees Fahrenheit (0-60 degrees Celsius). When temperatures drop below 20 degrees Fahrenheit (-7 Celsius), the driving range of EVs can decrease by up to 12% compared to 75- degree conditions, according to The American Automobile Association. UP winter temperatures often plunge well below freezing, so EVs face practical limitations.

The Role of Politics

Political attitudes also play a role in shaping EV adoption. Policies that encourage EV use, such as subsidies or incentives for charging infrastructure, can shift public perception. However, in rural areas where residents may prioritize practicality over innovation, political resistance can slow progress. Differing political priorities have influenced Michigan counties’ responses to EV adoption. Here is a quote from Glenn Stevens, executive director of MichAuto, which is affiliated with the Detroit Regional Chamber, that made me ponder about these statistics, “All seven of the EV-loving counties went for Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election. That’s a reality that speaks to the ‘highly politicized’ nature of EVs.”

On March 12, 2025, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced that they would begin efforts to reverse the vehicle emissions rules that the Biden administration implemented. The previous rules enforced required automakers to increase the number of electric vehicles being built. The Trump administration is undoing several actions done during Biden’s term, such as rescinding a 2022 regulation that aimed to decrease smog-and-soot forming emissions from heavy duty trucks (Shepardson, 2025).

At the same time, political leaders in Michigan are trying to find a balance between their values and the reality on the ground. Many Republicans support rolling back federal EV mandates, but some are worried about the impact on local economies that are starting to benefit from clean energy investments. Michigan Congressman John James, who has been critical of Biden’s EV policies, celebrated the end of what he called “EV mandates”. But he also warned that Congress should proceed with caution when it comes to cutting EV-related tax credits and manufacturing incentives, since job creators in his district rely on them. This is something UP officials might want to pay attention to. Even if EVs don’t feel especially relevant to the region right now, the federal investments connected to EV infrastructure and manufacturing could bring economic opportunities that are hard to ignore.

Final Thoughts

While not everyone sees widespread EV adoption as a priority, especially in areas where political resistance or skepticism remains strong, there are still good reasons to consider what a future with more EVs in the UP might look like. For that to happen, several things would need to change: more accessible charging infrastructure, lower vehicle costs, better performance in cold weather, and supportive policies at the local, state, and federal levels.

Switching to an EV in the UP requires significant lifestyle adjustments. For many, the challenges of affordability, infrastructure, and functionality outweigh the benefits such as not paying for gas. Until political attitudes and policies evolve, and technology costs improve, EVs will continue to be a rare sight in the UP. Creating a welcoming environment for EVs in the UP will be beneficial to many and create opportunities for more visitors (and their tourist dollars) in the summertime.

Adopting EVs in the UP is not impossible, but it will require a concerted effort from policymakers, manufacturers, and the community. The journey to an electric future in the UP may be slow, but with the right changes, it is possible to pave the way for EVs to have a home in our unique and rugged region.

A trip from my home in the Western Upper Peninsula to the SE Michigan metro area is a 9-hour, 550-mile drive. I will not buy an electric vehicle until

– charging the battery is as simple and QUICK as filling your gas tank;

– charging stations are as readily available – with NO WAITING – as gas stations;

– and free, clean, climate-controlled restrooms are available.

A Tesla can get 350-400 on a full charge. If you’re fully charged when you leave home, you only need to stop one time for like 20 minutes. So your 9 hour trip takes 9 hours and 20 minutes. Is that really the end of the world?

Not sure there is much interest in EV’s in the UP. Of more interest would be a study of how many households do not have access to basics like electricity and high-speed internet. I realized some people prefer to be off-grid, but in other areas, such as where our camp is, there is no electricity. I would think the local government officials would be advocating for both to all the taxpayers.

Another factor not considered in above article is the extremely high (& rapidly increasing) cost of electricity in the UP.

EVs are an inevitability given the success they are having globally. Yes, they are currently more suited to local (sub-400 mile) trips. My own commute from suburban DC to Alger County wouldn’t permit the use of such a vehicle but the average trip length of a car in the United States in 12 miles, for which EVs are well suited.

The issue is not political. Infrastructure to support these vehicles is needed and communities that fail to do so only harm themselves economically and environmentally. This is an easy win for everyone…it creates jobs, supports US auto manufacturing and reduces emissions which in turn helps improve human health and the environment.

Will I buy an EV…maybe for my wife’s commute to work but for now I will still need an ICE pickup truck for my farm in Alger County.

My spouse and I live in Delta County. We have a Kia Nero EV; we love it. I use it to drive to town and haven’t been to a gas station since October 2024. We slow-charge at home. We have used it to travel to visit family over 8 hours away. One stop at a charging station in Green Bay along the way is all it takes. The station is always readily available, no waiting. We don’t mind that it’s not as QUICK as filling a gas tank. It takes less than 20 minutes to charge what we need. During that time, we go into the adjacent Meijer, buy a snack, use the restroom which is clean, free, and climate-controlled. Not a hardship.

We know that EVs are not completely carbon-neutral in their production, but we want to mitigate emissions for future generations. Vehicles produce the 2nd highest amount of carbon dioxide in this country. (US is no. 2 in world greenhouse gas emission.)

a couple years ago I drove my newly purchased tesla from Arizona to Marquette (2,200 miles each way) and back to Arizona. Every supercharger was 1/4 mile or less off the highway/freeway. Most next to a mall, grocery chain, gas station, restaurants, etc. Charge time 10 to 40 minuets to get “continue trip” notice. (barely time to hit the restroom and grab a snack/soda) Charging stations are now open to several non tesla car brands and there are 3,4 or more other charging station companies adding more locations. I use EVgo for my Chevrolet Silverado EV pickup. Like it or not, it is the future and is available now. When in Arizona I charge from home with solar panels, so although my “fuel” isn’t “free”, it is “prepaid” from the solar panels which also powers the house. I admit that this isn’t currently an option in the UP.

“When temperatures drop below 20 degrees Fahrenheit (-7 Celsius), the driving range of EVs can decrease by up to 12% compared to 75- degree conditions, according to The American Automobile Association.”

I never understand this point. You make it sound like your gas car doesn’t lose mileage in winter. Newsflash, gas vehicles lose 10-20% of their range in winter. I know this from my own car! Same thing when these article say EVs don’t get as good range when pulling heavy loads. Well, does your truck magically get better range when it’s hauling a load?

Second, fast charging stations are possible. Look at Norway. They’re further north with harsh winters and 90% of their new vehicle sales in 2024 were EVs. They got over 9,000 fast chargers.

As someone who recently switched to an EV (and still has a gas-hybrid for second car), I tell people look at your own daily use. Where I live now, I commute over 20,000 miles a year locally. I don’t take a lot of long road trips. Maybe some moderate 2-3 hour ones, but rarely something major. I just got a level 2 charger installed in my garage (about $1,200 for charger + installation before credits from gov’t and local electric company, so some like Ford are doing incentives to install them for free). It’s so nice to be able to fill up anytime at home now and pass by all those high priced gas stations! Let me guess, that’s going to cost a lot in electricity, right? Here, I’ll go by the MBLP’s rate of 12.6 cents per kWh. To charge from 10 to 80% takes about 57.4 kWh on my car. That’s $7.23. To fill up 8 gallons on my Hybrid would cost $24 with gas about $3/gal. My hybrid gets about 1.5x the range as my EV, so $11 in electric would be the equivalent. Still cheaper. There’s little maintenance, and I got a 10 year, 100k warranty on the battery.

Longest drive I’ve made is 625 miles in one day. Took about 11 hours with two stops of 30 minutes each. My car takes 28 minutes to charge from 10 to 80%. The fastest ones available in the U.S. charge in 18 minutes. In China they now have 5 minute charging (sadly we prob won’t see those anytime soon). Plug in, go use the restroom, get a snack or chill for a few minutes. Honestly, as someone who used to do 2000 mile cross country trips and push the limits on my drives to get there as fast as I could (gas and go), taking a 15 minute break to stretch and walk around is much better on my body (ain’t getting any younger!).

For my situation, it just made sense. Not to mention, EVs are extremely fun to drive! Put your foot down on a 400hp dual motor AWD car and take off like a rocket and tell me that’s not intoxicating! I’d recommend any doubter to go test drive one.

The biggest hold back to mass adoption in the U.S. is simply the price. Next recommendation: DON’T buy a new EV. Buy a used one with low mileage that’s a year or two old. A new Hyundai Ioniq 6 MSRP is $45,000, after incentives $37,000, and you find a two year old model for low to mid $20s. Some, like Hyundai and Polestar, will sell certified vehicles with the full original warranty (typically 100k miles) and in some cases additional on top of it included.

Remember, you are buying technology, and you can never stay ahead of technology without paying a premium until mass adoption happens. Who remembers the first HDTVs back around 2007 when the digital switch occurred? I knew someone who paid $4,000 for a 65″ HDTV. Just a straight up TV. No wifi, no apps, nothing. Today you can get a 65″ 4K UHD TV with wifi/apps/the works for like $400.

That said, they really do need to figure out a way to lower the prices dramatically. China (BYD specifically) is flooding the world with cheap EVs ($10-20k for something you would pay $50-60k+ in the U.S. for), and legacy automakers are losing major market share internationally because the simply cannot compete price-wise. Ford’s CEO knows this. He drives a Chinese EV (Google it). We’ll see what their big announcement/reveal is in a few days.

Thanks for your article, thought provoking. Approx 1.7 M Eva sold in the us in 2024 which was a 7% increase. If we have a 10% increase that numbs will go to 1.9M approx. Out of 15+M total sales.

We will probably see more evs as a 2nd car in local or urban areas as a short distance vehicle where charging either at a residence or charging stations is more accessible and cost effective.

Total cost and convenience of usage will always be a factor in one’s purchase. Evs with their federal subsidies going away will have higher initial costs, plus the option of having an in home charging system, insurance costs may be higher and maintenance locations not as plentiful v ice autos.

Also, as we integrate more evs and more AI into the power grid how will we sustain, maintain, and supply power for these needs.

In the future we will see a need for alternative types of vehicles, I am just not sure it will only be evs. It could be hydrogen fuels, LNG! or even small nuclear power plants.