Euro-American Commercial Fishing in the Eastern Upper Peninsula – Part One

“Rural Voices” shares cultural, educational, economic and artistic views of people who have lived and thrived in the Upper Peninsula. Each of our authors in Rural Voices may be living here in the U.P. or living someplace around the globe, but the U.P. is an important part of who they are and what their beliefs and values are today. Rural Voices wants to share the voices of our neighbors and friends about life and experiences in the UP.

The following is the first part of our two-part series featuring local historian Russell Magnaghi’s piece “Euro-American Commercial Fishing in the Eastern Upper Peninsula.”

Commercial fishing in Michigan and specifically in the eastern Upper Peninsula is a complex story that has been influenced by economic concerns, political and legal battles, and by ecological changes in fish species.

This study focuses on the development and expansion of Euro-American fishing in the eastern Upper Peninsula of Michigan through a number of fishermen and family enterprises.

Unfortunately, a history of commercial fishing in Michigan or specifically the Upper Peninsula is lacking. This short piece will provide the audience a general idea of the nature of Euro-American commercial fishing rise and decline during the last 190 or so years.

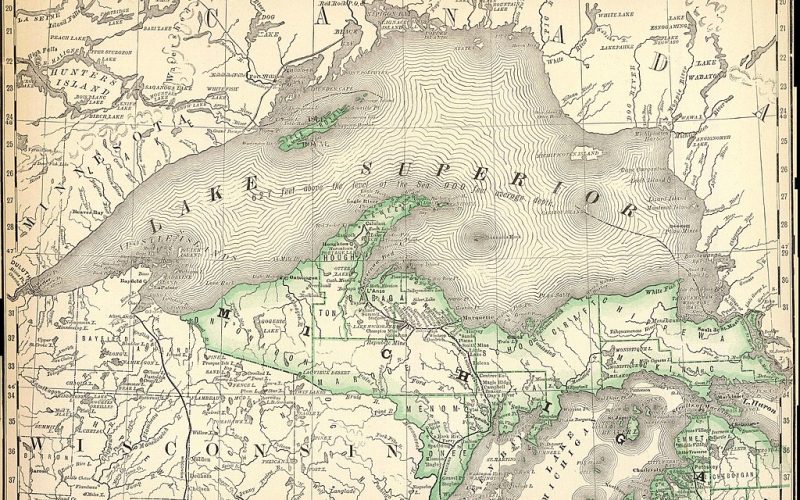

The region under discussion includes the area from the St. Mary’s River and Lake Huron on the east to a line between Grand Marais in eastern Alger County to Manistique, Schoolcraft County in the south. Within this area the two centers of early Euro-American settlement and commercial fishing were the Straits of Mackinac on the south and Sault Ste. Marie on the north.

In the late nineteenth century, a number of new fishing communities developed to the west of St. Ignace at Gros Cap, Epoufette, Naubinway, and finally Manistique.

The waters of the Straits of Mackinac, Lakes Huron and eastern Superior, the stretch of coast from Shelldrake River on the east to Grand Marais on the west, and the St. Mary’s River abounded with a variety of fish and lake trout and white fish dominating the early scene. Traditionally the Native Americans fished these waters and fish provided for nearly seventy-five percent of their diet.

On their arrival, the French quickly noticed the abundance of fish, especially the whitefish. Their maps of the Straits of Mackinac boldly labeled the area as home to the whitefish or poisson blanc and covered portions of their maps with fish icons. The Jesuit missionaries repeated the fish story of the Great Lakes. They wrote of the clear cold waters and the abundance of fish.

In the early days, fish was traded by the Native Americans to the French and then the English and Americans for goods.

The European traders brought fish hooks and other fishing equipment with them to trade to the Indians. In a “Certificate of Expenditures” for October 1779 to March 1780 it listed the importation of iron for “making Fish Hooks” although it does not explain if they were for trade or use by the English.

Two years later, eight dozen fish knives for chiefs, seventy-two dozen fish hooks, and one hundred two pairs of Canadian spears were invoiced to Fort Mackinac. Obviously, some of this equipment was scheduled for trade with the Indians, but possible other materials were to be used by the military and civilians on Mackinac Island.

The abundance of fish was clear from a variety of sources in the nineteenth century. In a February 1814 report, Captain Richard Bullock of Fort Michilimackinac reported that the English garrison had to rely on corn and fish – “of the latter we have been fortunately successful in obtaining a good supply, and on which we must exist until Provisions can be sent to us.”

A resident of Michilimackinac, James Finch in the early 1820s petitioned the U.S. Army for one hundred acres of land within the Fort Brady reservation at the Soo to develop a fishery. We do not know the results of the request, but it is obvious that individuals saw the growing value of the local fish supply.

Territorial Governor Lewis Cass in June 1820 wrote: “The supply of fish at [Sault Ste. Marie] is abundant and inexhaustible with this resource Indians would absolutely perish.” In the summer of 1822. a visitor to Sault Ste. Marie wrote from the rapids of the St. Mary’s River, “we are daily supplied with the most delicious fish, the poisson blanc, or white fish, and also with the salmon, trout, pike, carp, and sturgeon.”

In 1859, an anonymous writer to the New York Tribune wrote that a two-hour trip across the Straits brought you to the Carp River, just north of St. Ignace, where you could quickly catch two hundred and fifty speckled trout.

He further noted that if you had a keen appetite for breakfast you could “go out with a Mackinac fisherman at break of day; help take up his nets in fifty fathoms of water, with twenty to thirty lake trout weighing from six to sixty pounds, and one hundred whitefish weighing from two to six pounds–and on your return a common breakfast will taste good.”

As Upper Peninsula historian, Alvah Sawyer wrote in 1911, “It [fishing] has continued to be an active participant in the furnishing of supplies to the wide world and is today an industry of large proportions.” However, he did write a bit critically on a following page, pointing out that fishing interests at St. Ignace and Mackinac Island “were formerly of such magnitude [it] has greatly declined, so that there is now but one large dealer [Chambers Bros.] at St. Ignace.”

Again, we get reports of the excellent fishing now focused on Whitefish Point in Lake Superior. In June 1832 U.S. Army Lieutenant James Allen, a member of Schoolcraft’s expedition to discover the source of the Mississippi River, wrote that “this point [Whitefish] is remarkable and important as a fishery of whitefish–as affording more, and a better quality, of that excellent fish, than any other fishery of the south shore of the lake [Superior] yet explored.”

In a concise report gathered during his brief overnight stay at the point, Lieutenant Allen provides us with some wonderful insights into the nature of commercial fishing at that early date.

Two former voyageurs-traders, Samuel Ashman and Eustace Raussin of the American Fur Company decided to venture into the unknown–commercial fishing. Neither man had any experience nor knowledge of fishing, but established a fishery at Whitefish Point in 1830. Their endeavor proved to be successful and spurred them to expand their fishery.

The fishery before them ran some fifty-four miles from Shelldrake River on the east to Grand Marais on the west. This area had a sandy bottom and gradually fell into deep water, and was favorable to safety and easy working of nets from canoes. The gill nets were eight fathoms or forty-eight feet in length and five to ten feet broad depending on the depth of the water. In fair weather, two fishermen could man and tend up to ten nets, and the early morning yield could be between one and six barrels of fish.

The fishing season ran in two parts: the spring season from late April to June 1st and the fall season from October into November. The whole season ran for approximately three months. The largest and the best whitefish were taken in the spring. Lieutenant Allen wrote that in no other lake fishery were so many whitefish “larger and better than others.” In the spring, the average weight of a whitefish was fourteen to fifteen pounds and twenty to thirty fish filled a barrel weighing two hundred pounds.

The whitefish from this fishery was considered excellent in quality. Between 1830 and 1832, Ashman and Raussin shipped 559 barrels of salted fish to Detroit while their competitors at the Point shipped 313 barrels. Any other whitefish fetched $1.00 to $2.99 per barrel. The Whitefish Point fishermen got $6.00 per barrel and thus they made $5,234 for their fishing endeavors during this time. On this high note, all Lieutenant Allen could say was that there were more fisheries to be discovered in Lake Superior.

An interesting development took place in the 1830s prior to statehood. The American Fur Company saw that its prospects for continuing to engage in a profitable fur trade were limited. As a result, it turned to the Native People to fish commercially for them.

They provided the salt, barrels and transportation, and the Indians provided barrels of salted whitefish for sale to the eastern market. The idea was sound and is an example of white men promoting commercial fishing among the Native Americans.

Unfortunately, a poor economic climate in the nation caused a drop in the demand for salted whitefish, and the American Fur Company ended up with warehouses filled with barrels of salted fish. Although they tried to promote the sale of the surplus to planters in the South for their slaves and even to a Mexican market, this proved to be an unprofitable venture.

By the 1840s, soon after statehood, commercial fishing was begun in earnest in northern Michigan. There was a growing demand for white fish for the eastern market. Although it was not in the Upper Peninsula, the following episode took place just to the south.

In the fall of 1846, Curtis Munger of Bay City gathered a group of entrepreneurs and went to Thunder Bay Island in Lake Huron and started a commercial fishing business. They remained there until the latter part of November 1848 when they planned on leaving for their homes. The oncoming winter caught them and they had a difficult time sailing their open fishing boat to Saginaw Bay.

The news of commercial fishing on the upper lakes attracted fish equipment suppliers like E.A. Lansing of Detroit. In the summer of 1847, he was the agent for the American Net and Twine Manufacturing Company of Boston. He reported in the Lake Superior Journal published at Sault Ste. Marie that he “will shortly be in receipt of several thousand yards White Fish gill nets, on Reels of from 500 to 1000 yards per Reel, 14 Meshes, double at top and bottom thereby giving the Net greater strength and more durability, 2 and 3 ply Twine 4 ½ inch, made from flax and sea island cotton.”

He continued, “Fishing Companies, or Individuals wanting any quantity of Gill Netting or Seine, of any variety, can have them made-to-order complete for use, and warranted the best quality, at prices entirely satisfactory.” At Sault Ste. Marie, O.S. Lyons & Company had for sale, “White Fish and Trout, in barrels and half barrels” while down the street merchant Peter B. Barbeau was selling “Seine and Gilling Twine, Fish Hooks and Fishing Tackle of every description.”

The first time that we can focus on commercial fishermen is 1860 some forty years after Finch’s request. At Mackinac Island and Sault Ste. Marie, the transition from Native fishermen to Euro-Americans fishermen can be seen for the first time. At Sault Ste. Marie there were eleven male and one female Native Americans listed as fishermen in the federal census of that year. Their total personal estate value was set at $3,400.

On the other hand, there were sixty-one Euro-American fishermen or 84 percent of the total. Whose total personal value was $13,600. There were no Métis or mixed people listed as fishermen.

New occupations developed in conjunction with the fishing industry. There was the essential boat building industry that had three individuals engaged in business. The cooper or barrel maker had been an important part of life in America since the colonial era. Different sized barrels were the basic means of transporting goods and the woods of the Upper Peninsula provided the raw materials for this product. At the Soo there were nine coopers who created barrels which were used to ship the salted fish to growing markets.

To the south at Mackinac Island there was another group of fishermen. Here only seven Native Americans were listed as fishermen while there were twenty-five Métis or mixed bloods and thirty-five Euro-Americans. If we count the non-Natives they comprised 89.5 percent of the fishermen at Mackinac, an industry that was once dominated by Native Americans.

Here there were a number of occupations more directly connected with the fishing industry. Occupations listed included: fishing hands (3 white, 7 Indian) and one each fish inspector and fish merchant. Peter A. Barbeau was a long-established French Canadian who came from Montréal and had grown wealthy on the boom trade that developed at the Soo.

He was a major player in the shipping of salted fish to eastern and southern Great Lakes urban centers. Although there were no boat builders listed, there were sixteen coopers providing their essential product to the fishing industry.

Thank you. I enjoyed reading this

Fascinating information. Thankyou for your research.