“Lost” Labor History of the Upper Peninsula

There is a long-neglected history of labor in the Upper Peninsula. The main reason for this is because workers did not have the time or the energy to write their history. As a result, most of the comments covering labor and its movement appeared in company histories. The local newspapers did not have time for labor nor its problems. In one example, C. Harry Benedict, who was an engineer and official with Calumet & Hecla, wrote of C&H’s relations with labor:

“With one most unfortunate exception that will be discussed in detail, the C&H had been particularly blessed throughout its history of peaceful relations with its employees.”

In a lengthy article, “A Bond of Interest,” in Harlow’s Wooden Man (Fall 1978, p. 8) the author, Wilbur “Waba” Treloar, took a company position when he wrote of the 1895 strike in Ishpeming:

“After a month, William G. Mather came north, saw the company’s mines being flooded and acted quickly. Help from the militia was requested and within a short time the strike was ended without violence. It was sharp, decisive action. But it should be taken in the context of the times. Organized labor had little influence in the iron country; work stoppage was an economic sin and miners just didn’t allow mines to flood.”

From this excerpt, it is obvious the author was more concerned about the flooding mines than the grievances of the workers. The newspapers of the era, one of the few sources available to researchers on the subject, tended to be anti-organized labor owned by businessmen with connections and stock in the mining companies. The Portage Lake Mining Gazette wrote in May 16, 1872, “The cowardly scoundrels that were instrumental in inaugurating the C&H strike . . .” and it went on to declare the company would “call in the aid of the whole machinery of the State to do so [end the strike]” and those involved consisted of a “criminal mob.” On May 9th, it stated that dissatisfied workers “can go elsewhere to labor.”

Throughout their existence, the publishers of the Iron Agitator and Iron Ore of Ishpeming were critical of organized labor. The “happy workers” were always being portrayed as being led on by outside agitators who did not know what was best for the miners. The inaccuracies of the alleged state of the miners being “happy and content” in the Upper Peninsula can be seen in the 1910 census. Here, it is reported that in Montana, where the miners were unionized, all of the copper miners in 1909 gained an eight hour day.

In Michigan, three of the forty-six iron companies had eight hour days, and the other forty-three had ten hour days. Out of the twenty-five copper companies, twelve had less than eight hour days, nine companies had eight hour days, and five had ten hour days; so much for the “happy and content workers.” Furthermore, the better working conditions, wages, and hours attracted many Upper Peninsula miners to other locations in the country, as the newspapers show.

There was a constant movement of people from the area to the Illinois coal mines, copper mines of Butte, Montana or the silver mines of Tonopah, Nevada. There were also many Finnish miners attracted to the coal mines of Red Lodge, Montana. Miners continuously moved from the copper and iron ranges of the UP to the Iron Range of Minnesota and back seeking better wages or to avoid lay-offs during a strike.

Throughout the history of the Upper Peninsula, there was a constant demand for laborers. The region was isolated and there was no local population that could fill all of the demands for laborers in the many expanding industries that developed in the nineteenth century. When Charles Harvey directed the construction of the locks on the St. Mary’s River, he had to import Irish workers for the job. In the 1890s when the power canal was being dug at Sault Ste. Marie, Italian workers were imported from New York. The same was true of railroad construction and section hands on the Duluth, South Shore & Atlantic Railroad across the Peninsula.

The companies maintained a labor force by using employment agencies in the large cities. These agencies sent representatives to Europe in order to recruit workers and encourage workers to write for friends and relatives. As a result, most of the workers in the mining areas were foreign and the Upper Peninsula had a larger concentration of foreigners than any other location in Michigan except for Detroit.

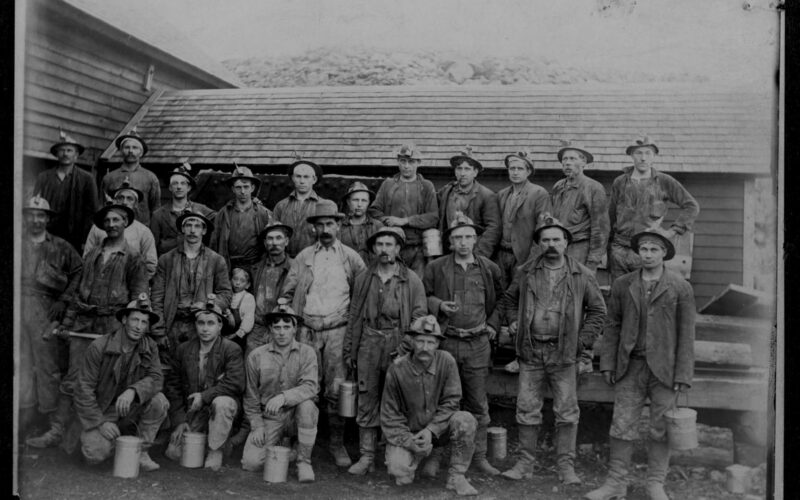

The workers labored under primitive conditions in the mines and woods, and there was little concern for safety. For instance, it was not until 1910 when William Mather of CCI finally introduced safety measures after twenty men were killed in the previous year. The wages fluctuated with the economy. Company officials served as township officials and the company provided all of the necessities of life. Without the secret ballot, this was seen in one’s best interest to vote with the company.

So life was made comfortable by the companies, but the freedom of the people was greatly reduced in the process; freedom was given up for security. In many cases, the living conditions in the Upper Peninsula were better than those found in Chicago. Accidents were common, especially if a person let his guard down. The hours were long, wages were low compared to western mining wages, and there was no job security, unemployment, nor accident insurance. Thus, there was reason for labor organization.

The organization of labor was extremely difficult throughout the various industries in the Upper Peninsula. First of all, the population was scattered in three mining iron ranges and the copper country, making organizing efforts extremely difficult. Most of the laborers were European immigrants, so there were national jealousies and language barriers to overcome. However, various organizations formed in the Upper Peninsula, such as the Knights of Labor. Various local unions formed and then dissolved. So there was some attempt at organizing in the nineteenth century.

The labor forces did not remain quiet and content with their lot. Local newspaper and labor statistics show there were many strikes despite what companies officials said. One of the earliest strikes was directed toward C&H early it is history. The number of grievances accumulated during the economic hard times between 1867 and 1870. The real wages were driven down to an unusually low level immediately following the Civil War.

Nerves were frayed by the depressed state of the mining industry and the insecurity of employment. In 1872, there were labor shortages and dissatisfaction continued with many workers shifting from mine to mine seeking better conditions in spite of general and heavy wage increase. In May, the employees in the Portage Lake and Calumet areas went on strike seeking a wage increase and an eight hour day.

The strikers refused to let strike breakers take their positions. The strike lasted three weeks and collapsed after the companies called in a company of infantry brought up from Detroit to Houghton. The Mining Gazette of Houghton warned against radical eastern ideas and stated, “Nothing more thoroughly un-American in practice and in principle can well be concerned than trade unionism.”

In 1874, when an “outsider” appeared at C&H property and “incited” the employees, he was promptly arrested and the Mining Gazette wrote, “it is high time a class of men in this country were taught that the rights of a corporation are just as sacred as those of an individual.” At this time, Alexander Agassiz, president of C&H wrote that he would not be dictated to by labor and would rather close the mines than deal with labor.

In 1887, C&H hired a private detective service, which reported there was no organization, and this was after a disastrous C&H fire. The Knights of Labor had a foothold in two foundries. Agassiz created a company union to keep the men happy. He also did not hire Knights of Labor men and discharged any of its members. In July of 1890, there were demands for shorter hours which cumulated in the strike at the stamp mill.

Early in 1891, the final vestiges of the Knights of Labor were destroyed. In 1904, the Quincy, Atlantic, and Baltic lodes lost about three week’s productions. In 1892, 1894, 1896, and 1897, following in the wake of economic hard times, there were a number of occasional short strikes at different properties, always among trammers/shovelers Company reaction was usually to grant compromise wage increases and sometimes to refuse to take back strike leaders. These strikes had little effect on the production of the industry, but they did show a growing dissatisfaction with conditions.

Reasons for these strikes: tramming was extremely difficult work, men heard of unionization elsewhere in the mining world, and people were restive over company paternalism in their lives. In 1900, C&H opposed the creation of a street railway fearing that it allowed the men to get together in times of strike. On June 21, 1890, trammers – Poles, Slovenians, Croatians, and Finns – struck at Tamarack demanding increase from $2.00 to $2.25 per day.

During these years the mining companies in the Copper Country quickly promoted the creation of the Tamarack Cooperative. The idea was that the cooperative store could offer reduced prices and thus the companies would not have to raise wages. Within the few years the miners gained control of the board of directors and the cooperative became the largest department store north of Milwaukee benefitting the workers. Finns, Swedes, Italians, Hungarians and Croatians all developed cooperative stores across the UP in order to buy food at reduced prices.

In the Marquette Iron Range, unionization was a story of defeat and frustration until the mid-20th century. There were several major strikes in the 19th century. By the summer of 1874, the effects of the Panic of 1873 were being felt in the central Upper Peninsula. In 1874, when the price of iron dropped, the employers cut wages which, except for contract miners, went down to $1.30 – $1.75 per day.

Strikes followed at the Cleveland, Barnum, New York, and Lake Angeline mines and the streets were filled with idle miners in Ishpeming. The sheriff feared the worst and asked the governor for the state militia. Two companies of troops were sent from Detroit and the Marquette militia company organized earlier , was sent to Republic to crush any labor uprising. The troops found little to do except to patrol. During the strike, most of the mines shut down and the men were paid off and as was a common practice some of the men left the area.

The biggest strike in the 19th century occurred between July 15th and September 16, 1895 as a result of the Panic of 1893 and poor economic conditions that followed. Prior to the strike, the workers received very low wages and the season’s output was a record breaker. In March 13, 1895, the reporter for the Marquette Mining Journal wrote, “It can’t be denied that they are working now for wages too low to compensate them adequately for the kind of work required of them and the risk they run in an extra hazardous occupation.”

On July 15th, the miners of the Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company went on strike for higher wages. At 11:00 a.m., five hundred Negaunee and Ishpeming men marched to the Lake Superior Section 16 mine, and waited for the men ending their shifts to come and join them. The action quickly spread and by the following day, there was an energetic walk out of the Ishpeming mines.

By the 3rd day, between 200 and 300 miners were meeting at Union Park in Ishpeming to show they were determined to stay out. Parties with as many as five thousand miners were held to show that the laborers were united. By July 26th, mechanists, engineer foremen, brakemen, and steam shovel men all joined the miners.

During the first week of August, the Republic Iron Mining Company gave their workers an advance in pay to keep them from joining the strike. The mine officials wanted to meet with the union representatives to negotiate, but the miners continued to show their solidarity and would not weaken. Finally, on August 15th, F. Braastad, lessee and operator of the Winthrop mine, was the first to submit to the new scale of wages.

There was a ten to twenty-five percent increase, but the mechanics were not mentioned. During these negotiations the various companies presented propositions but neither side was giving in, and the miners cried, “we’ll beg before we give in.” At this time, CCI decided to pull the pumps out in different mines, contending that it was cheaper to let the mines fill with water rather than keeping them pumped. Late in August, the miners rejected the companies’ scale of wages and many men left the area.

By the end of August, the water was rising fast in the Lake Angeline and Lake Superior mines. Companies were preparing to start the shovels, so they sent a delegation with a request to resume work. It was rejected, and the shovel men declined to work. The companies had outsiders take the job.

The miners refused terms given to them by the company; even union leader William Coad told them to accept. He finally resigned, which was accepted by the miners. Braastad, however, accepted the terms, but they did not take effect. Finally, William Mather returned on the scene and the company took action.

During the week prior to September 14th, the men received a charter from the Miner’s Union/American Federation of Labor. Talk of compromise was in the air and it was felt if the wages were slightly increased there would be a compromise. During the week of September 16th, in a 700 to 600 vote, the wage package was accepted: a slight increase over the regional wages. However in the process, many miners left for Vermilion, Gogebic, and Mesabi ranges.

By 1896, there was an increase in wages due to the rising ore prices. A year later, they further improved because many miners were leaving their work for the higher paying lumber camps; this was especially true of the Finns.

Labor also organized on the Gogebic Range. In May of 1894, the newspaper Lake Superior Citizen announced a call for a labor convention to place to nominate candidates for the road commissioner. Notices were posted by a self-constituted labor committee in Bessemer. They were to meet in various wards to select delegates and then meet in convention on the following day.

When the working men arrived at the location, they found the door locked and a notice stating the meeting was postponed until 8:00 p.m. The workers thought they had been defrauded. They organized in the street and found a place to meet Scandinavian Hall. They went to the Ironwood meeting the next day, but were not allowed to enter. After this incident, the workers created an independent movement and invited workers from Ironwood and Bessemer to join them. Of the five positions in the June election, three were won by laborers.

Labor strikes in other industries throughout the Upper Peninsula were common. In 1881, railroad brakeman in Marquette went on strike; June of 1886 – sawmill employees; 1885 – three mines closed sawmills in Menominee. In March of 1886, eight railroad workers on Detroit, South Shore & Atlantic in Chippewa County went on strike. Later, on June 24th, 650 Italian workers on DSSA at L’Anse went on strike.

In 1895 when a number of telephone workers went out they were immediately fired and replaced. May 17, 1892 cigar makers for Jaedoecke Bros. factory in Marquette struck. May 15 1899 the Menominee River Shingle Mill out on strike. These strikers were listed and recorded by the Michigan Bureau of Labor and Industrial Statistics which recorded them. This bureau was created in 1883.

One interesting non-mine strike was against the Duluth, South Shore and Atlantic Railway in March of 1887. On March 8th, about 350 laborers on a construction gang along the Sault branch in Chippewa County went on strike. They wanted their wages raised from $1.50 to $2.00 per day, and their other grievances included ill-usage from the sub-contractor.

In typical fashion of the time, Sheriff McKenzie of Sault Ste. Marie led a posse of armed men to the camps and forced about fifty troublemakers to leave. The remaining workers returned to work on March 14th. In a letter to the Bureau of Labor, it was stated this was a poor place to work because, besides the poor wages, the men had very poor food and they had to live in camps with terrible conditions.

With the strike broken, the men returned to work for their old wages and on April 1st, the wages were raised to $1.75; however, the price of room and board was raised to $4.00 per week. Strikes against the DSSA were common. On June 24, 1887, on the Summit Division, 650 Italian workers went on strike. The men became belligerent, and the sheriff and fifty deputies arrested seventeen ringleaders. Within two days, the men were back to work at the old salaries.

Unionization occurred among non-mining workers. By 1907, the following occupations were unionized: barbers, brewery works, brick and stone masons, carpenters and joiners, cigar makers, electrical workers, iron molders, locomotive engineers, longshoremen, plumbers and steam fitters, railroad trainmen, railway conductors, shingle weavers, street and electric railway employees, teamsters, typographical workers, and car workers. However, these jobs were unionized only in certain communities.

In 1907, the various unions came forth with demands they felt would aid labor. These included: an eight hour work day, end of cigar manufacturing in the state prison, a postal savings bank, enforcement of child labor laws, repeal of employers’ limited liability, direct election of U.S. Senators, just female labor laws, and compulsory sanitation laws for all factories and workshops. Many of these suggestions would be enacted into law on a national and state level during the Progressive era which ended after World War I.

In 1910 the Western Federation of Miners, which had gained membership and strength in the Far Western mining districts, led successful organizational moves among the Upper Peninsula miners. The most infamous strike in the Upper Peninsula was centered in the Copper Country between August 1913 and April 1914. When the strike ended basically little was accomplished to improve the lives of the miners.

The organization of labor remained dreadful until July 5, 1935 when President Franklin Roosevelt founded the National Labor Relations Board which was created by Congress. The Board is an independent agency of the federal government with responsibilities for enforcing United States labor law in relation to collective bargaining and unfair labor practices. As a result of this labor in the Upper Peninsula was finally able to successfully organize in the years after World War II. So despite what company historians have written about the “happy” workers who never tried to strike or organize the opposite was true.

Very interesting. My great-grandfather from Finland lost the lower part of an arm in a mining accident in the U P.

Are you related to the Anderson / Lahti (sp)?

Very well done….Thank you for sharing this insightful article

Thanks Russ, your reports are always interesting and informative.

Always interesting Russ and thank you. Reminds me of the stories I heard from my grandfather and uncles regarding similar labor management issues and union busting intimidation tactics led by Ford’s own in house “head busting” security force at the Ford Motor Company in Kingsford MI.

thanks and I am filling in all of my families” background. my uncle Blondie worked at the c an dH tool shed in south Range. His father my Grandfather Antone jackovich was a copper Miner worked around dodgeville area. My grandmother Mary Jackovich (nee butkovich) grew up in calumet born there 1899. Her father was a mine captian so with the company against the miners during the 1913 strike. So his daughter married a nice, great left wing croation who came out from Trieste about 1910. So its highly unlikely my great grandfather and my grandfather would have ever got along. I just wish the 1913 strike and the Italian hall disaster would have been taught throughout the 50,60 and 70,s so everone would know the story. I Knew vagually about it from family snippetts, but the Woody Guthrie song 1913 Massacre really pointed me to it in 1970. I live in Auatralia much of the time but have a little place in Keewenaw which I get back to every year. thanks, dr tom forsell

[…] in the Upper Peninsula “were restive over company paternalism in their lives,” writes historian Russell Magnaghi. Company bosses often doubled as township officials, and the company provided the links to many […]

[…] in the Upper Peninsula “were restive over company paternalism in their lives,” writes historian Russell Magnaghi. Company bosses often doubled as township officials, and the company provided the links to many […]

I would love to know if there is anything around Bakery or similar industry, being unionized prior to 1990 in the area. Or, worker cooperative. Which is what I would be most interested about.

I understand Zingermans of Ann Arbor is a worker Coop, and that has fascinated me for some time.