Population Decline is Not Inevitable: Evidence from the Northlands

Figure 1: A new housing development on North Twin Lake, Vilas County.

American rural areas lost population throughout much of the twentieth century, and they continue to decline here in the twenty-first.

So-called “rural amenity areas” are the exception: locations possessing natural features like mountains, lakes, forests, and rivers, which provide recreation opportunities for affluent migrants and retirees.

In contrast, rural areas that depend on traditional employers, like mining and agriculture, continue to lose population as young people seek economic opportunities in cities. These national trends are ongoing in the counties surrounding Lake Superior, as 14 of the 15 UP counties lost population between 2010 and 2020. Total employment also fell, continuing the region’s long-term decline.

However, in northern Wisconsin and Minnesota, a different story is being written.

Vilas County, across the state line from Gogebic County in the western UP, has been gaining population since the 1970s. A similar pattern is evident in Bayfield County, WI, home to Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, and Cook County, on Minnesota’s north shore.

All three counties share geographic similarities with their UP counterparts: sparsely populated, isolated from major urban centers, heavily forested with numerous lakes, and, in the case of Bayfield and Cook counties, have Lake Superior shoreline.

But unlike most UP counties, their populations have been on an upward trajectory for decades.

This article examines the recent effects of population gains in Vilas, Bayfield and Cook counties, using data compiled from sources at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Results suggest that greater consideration should be given to attracting baby boomers as a means of promoting economic development in the UP.

The population dynamics of the UP are well documented. For the past decade the number of deaths has exceeded the number of births, while net migration (the difference between the number of number of in-migrants and out-migrants) is insufficient to offset the imbalance. The result of this process is population decline.

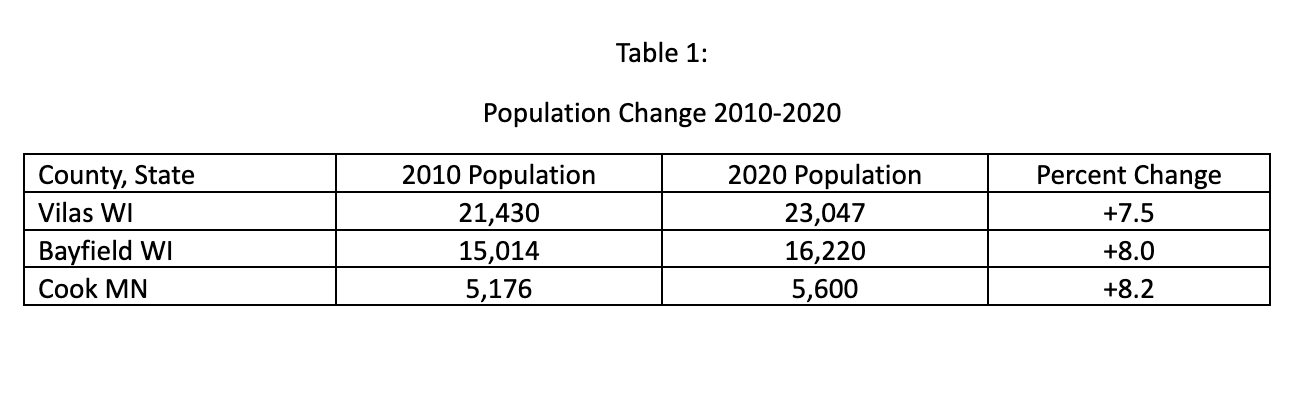

A similar dynamic is evident in Vilas, Bayfield and Cook counties, except that net migration is sufficiently high that all three county populations are growing (Table 1). Between 2010-20, the state of Wisconsin’s population increased by 3.6%, Minnesota grew by 7.6%, yet all three rural counties had higher population growth rates than their respective states.

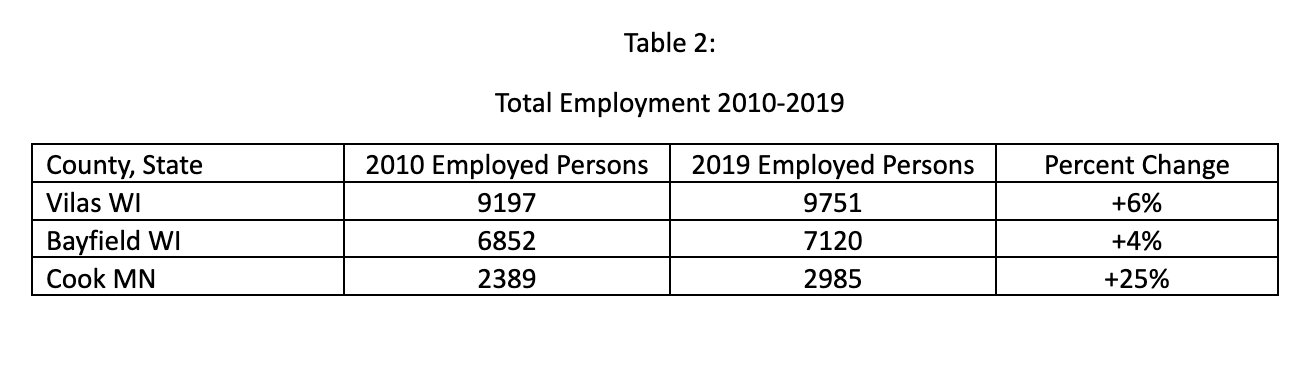

A growing population means a rise in the demand for goods and services. Building permits for new private home construction between 2010 and 2020 totaled 1,966 for Vilas County (Figure 1), 805 for Bayfield and 613 for Cook. Population growth has also boosted employment (Table 2).

Between 2010 and 2019, prior to the onset of the Covid 19 pandemic, Cook County’s total number of employed persons increased by 25%, while Vilas and Bayfield experienced single digit gains. In the UP’s three largest counties, Marquette, Houghton and Chippewa, total employment fell during the same period.

An examination of population structure indicates that retirees and middle-aged persons constitute most of these population gains. In 2020, the median age in Vilas County, Bayfield and Cook counties increased to over 50, while their respective state’s median ages are in the upper 30s.

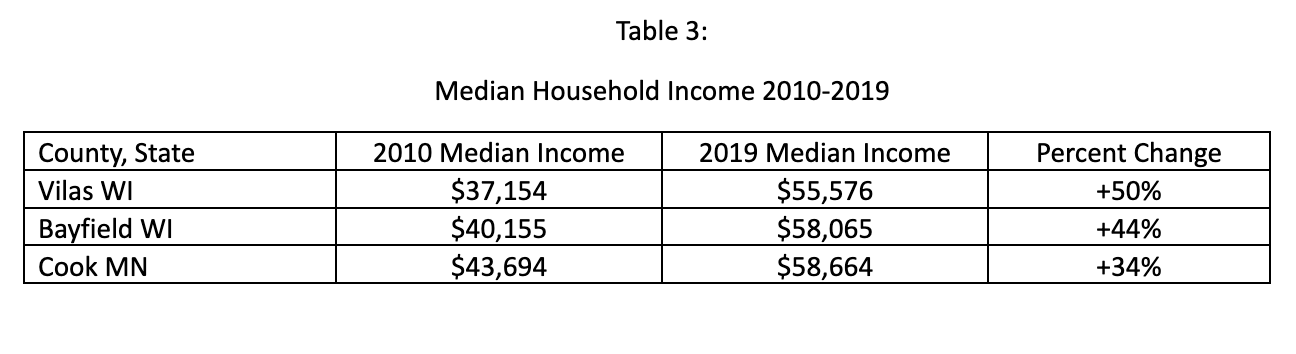

These newcomers’ moves are permanent, which has led to significant gains in median household income (Table 3). Median household income in Vilas County, for example, in 2019 was $55,576, a fifty percent increase from 2010, while Bayfield’s gain was forty-four percent and Cook’s was thirty-four percent.

The comparable figure for Marquette County, the UP’s most populous county, was twenty-four percent.

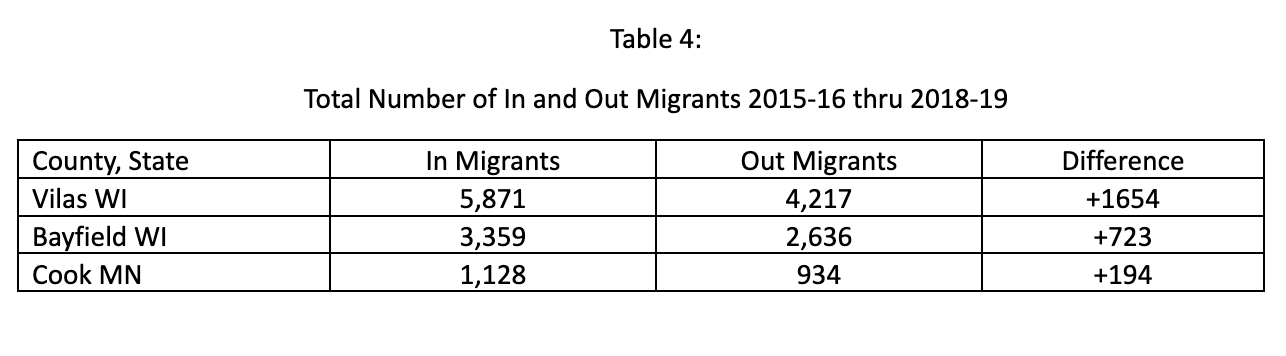

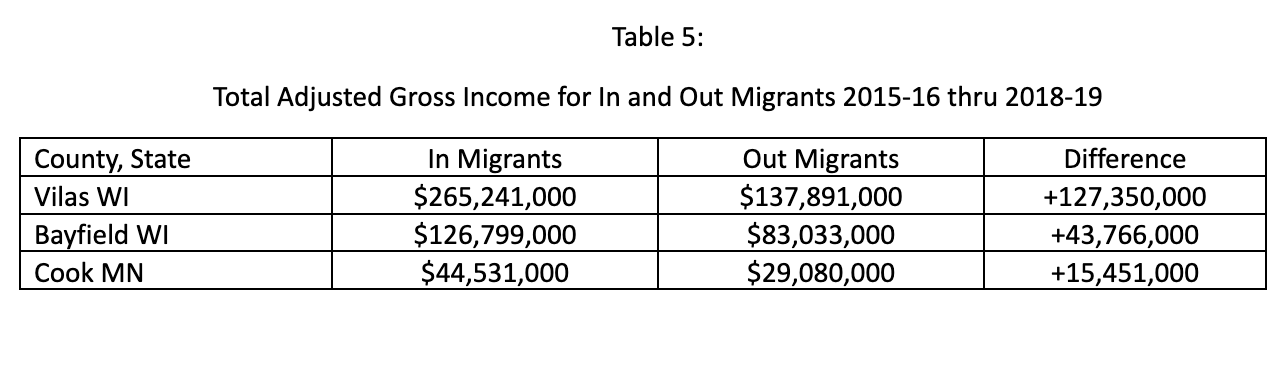

Comparing the numbers and incomes of in-migrants versus out-migrants, using IRS data, shows the value of newcomers in promoting economic development. Between 2015-16 and 2018-19, all three counties had more in-migrants than out-migrants (Table 4), while the total adjusted income of newcomers was significantly higher than those who left (Table 5).

In Vilas County, over the 4 year period, the total adjusted gross income of in-migrants amounted to $265 million, compared with $137 million for people who departed. This difference amounts to $128 million more in the local economy and is a significant factor behind boosting the demand for services and overall employment.

Migration theory predicts that most people only move short distances to places that they are already familiar with. Support for the theory is evident in Bayfield County, where the largest single source of migrants is from Ashland, the county that is immediately to its west, and in Vilas County it is Oneida County, to its south.

But for Cook County, Hennepin County (Minneapolis, 260 miles to the south) is its largest single source of migrants. This ability to attract long-distance migrants is also evident in Vilas, whose other major sources of migrants include Milwaukee, Dane (Madison), and Waukesha (suburban Milwaukee) counties, places that are over 200 miles away.

The benefits of attracting middle-aged and retiree migrants to rural amenity areas in the Northlands are evident in the form of gains in population, employment and household income. These gains, in turn, create additional demand for goods and services and boost the local economy.

Yet it is worth noting that new arrivals have unintended consequences such as increasing the strain on rural health care services, and boosting housing prices to make home ownership out of reach for long-term residents. These and other impacts can lead to resentment between newcomers and established residents.

The geographic differences between the western half of the UP and northern Wisconsin and the north shore of Lake Superior are minimal. Yet, on one side of the state line, population decline and slow economic growth characterize many areas, while on the other side the opposite it true.

The results of this analysis suggest that greater consideration should be given to enticing baby boomers and their retirement portfolios to the UP from places to its south, in contrast to traditional economic development strategies that focus on attracting and supporting existing businesses.

The evidence from Northern Wisconsin and Minnesota shows that distance is not a constraint on attracting newcomers and that elderly people are willing to forsake metropolitan amenities for the Northland’s natural beauty.

The challenge for policy makers is to find a balance between the need for economic development and the needs of long-term residents.

“The results of this analysis suggest that greater consideration should be given to enticing baby boomers and their retirement portfolios to the UP from places to its south”

I think that if it’s becoming difficult for young people to stay in the U.P., we should not increase that difficulty by turning the whole place into a retirement village. Isn’t a balanced population more desirable? Even at the cost of population growth?

What a difference a line makes. Compared to northern Mn and Wi, much of the UP is an inferior choice for relocating. Ditto state of Mi versus Mn and Wi.

Within the UP, Houghton/Hancock and Marquette are the only places adding population for same reasons.

The best explanation for this phenomenon is probably that state lines exert power over people’s geographic imaginations. Minneapolitans migrate north to Cook County, MN instead of Bayfield County, Wisconsin, even though Bayfield is closer to Minneapolis. Milwaukee residents stay within Wisconsin, and so forth. What the westen U.P. needs is some marketing to folks in Minnesota and Wisconsin who are geographically closer than Detroit or Grand Rapids. The only other explanations I can think of are physical geography – the lakes of Vilas County and the snow belt which falls almost perfectly along the Wisconsin-Michigan border.