The Big Beautiful Act, Medicaid and the Upper Peninsula

On July 4, President Trump signed into law the “Big Beautiful Act.” This law has many ramifications for Upper Peninsula residents, one of particular significance being changes to Medicaid.

According to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, the Act will cut federal spending on Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program benefits by $1 trillion, due in large part by eliminating at least 10.5 million people from the programs by 2034.

In opposing the legislation, the American Hospital Association stated that the cuts will cause “irreparable harm” to the healthcare system and increase uncompensated care for hospitals and healthcare systems.

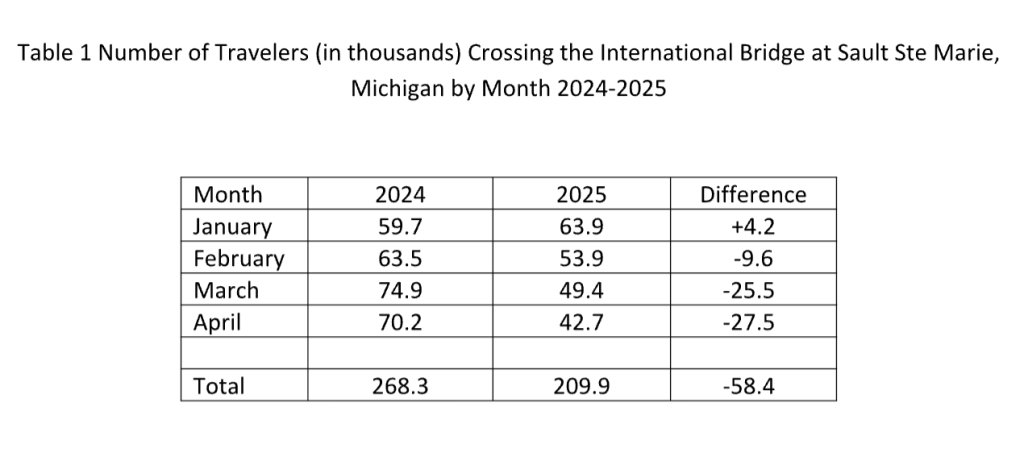

The cuts were similarly opposed by the nonpartisan National Rural Health Association. It issued a report on the Estimated Impact of Medicaid Enrollment and Hospital Expenditures in Rural Communities that highlighted the importance of Medicaid funding for rural residents (Table 1).

Medicaid “provides a financial lifeline for rural healthcare providers- including hospitals, community health centers, rural health clinics and nursing homes.”

These providers already confront significant financial challenges, with nearly half of all rural hospitals having negative margins. Under the Act, rural hospitals are slated to lose 21 cents out of every dollar they receive in Medicaid funding. The loss in funding, makes hospital and clinic closures inevitable.

This article considers the broad implications of the program cuts for the Upper Peninsula. First, some background information is provided on the origins of Medicaid, its growth, and the eligibility guidelines for recipients.

Medicaid 101

Medicaid was established in 1965 as part of the Social Security Amendments of 1965, with the goal of providing healthcare coverage to low-income individuals and families including children, pregnant women, the elderly, and people with disabilities.

The enabling legislation obligates the federal government to fund a portion of medically necessary healthcare expenses for eligible individuals. Financing the program is a joint responsibility of the federal government and states. The federal government establishes minimum requirements for states to operate a Medicaid program, specifying who qualifies and which services must be covered.

Beyond that, states can extend eligibility to additional groups and cover optional healthcare services. For example, under the 2010 Affordable Care Act, states can expand eligibility to adults with household incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

Forty states including Michigan and the District of Columbia have expanded their Medicaid programs in this way. The flexibility inherent in the program means there is no single Medicaid program, there are instead 56 programs, one for each state, the District of Columbia, and five permanently inhabited US territories.

The state of Michigan operates several Medicaid programs targeted at children, pregnant women, disabled persons and persons without health insurance. According to the state’s Health and Human Services website, the goal is to provide “essential healthcare services… to those who otherwise do not have the financial resources to purchase them.”

All programs have an “income test.” For its Healthy Michigan plan which provides healthcare coverage for individuals 19-64, enrollees must have an income at or below 133% of the Federal Poverty Level. In 2025 that figure is $20,815 for a single individual and $42,760 for a family of four.

Medicaid’s Growth

In January 2025, there were approximately 71.4 million people enrolled in Medicaid, with children accounting for 41 percent of this total, according to the Pew Research Center. The number of people enrolled in the program has increased since its inception due not only to population growth but also macro-economic conditions.

When people lose their jobs and income, many become eligible for the program. In the COVID-19 pandemic, when unemployment suddenly shot up, Congress gave states extra money for Medicaid and enrollment increased. These funds ended in December 2023 and enrollment has subsequently declined.

In Michigan, prior to the onset of the pandemic in January 2020, enrollment in Medicaid and Healthy Michigan (a state administered plan for low-income adults 19-64) was 1.75 million. By January 2023, the figure had increased by over half a million to 2.3 million, but falling unemployment and the withdrawal of extra funds from the federal government, enrollment dropped to 1.76 million in January 2025.

Medicaid in the Upper Peninsula

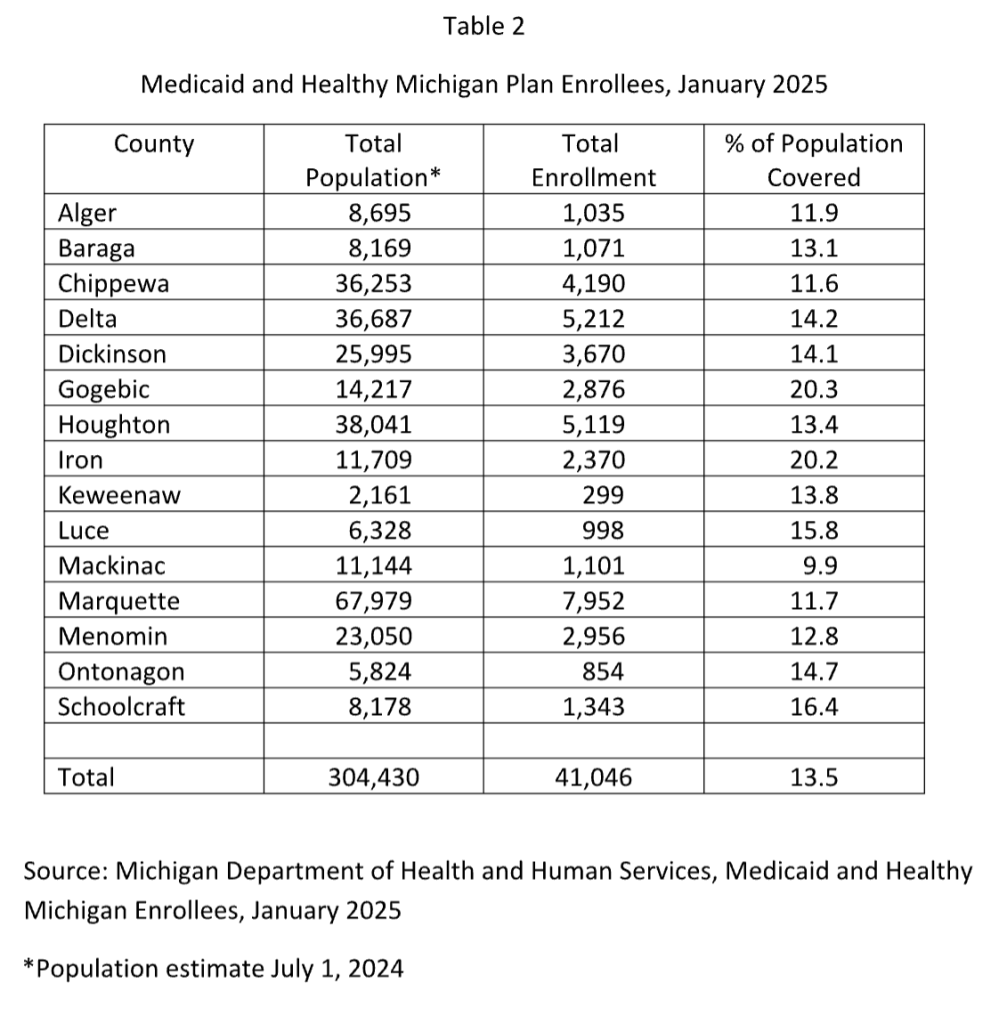

Over 40,000 people in the U.P. (or 13.5 percent of the population) were covered by Medicaid and Healthy Michigan in January 2025 (Table 2). Gogebic and Iron County have the highest coverage rate at over twenty percent of the population. Medicaid services for the entire Upper Peninsula are provided by the Upper Peninsula Health Plan (UPHP), a managed care organization based in Marquette.

In 2024, according to UPHP’s website, it paid $232 million (excluding pharmacy payments) to 4,666 providers in the region. The organization’s number of full and part-time employees was 191 in 2024, with a payroll of $17.2 million. UPHP’s role in providing Medicaid related services highlights one of the indirect effects of funding cuts beyond potential hospital and/or clinic closures, as fewer clients could mean layoffs for the managed care provider.

Rural hospitals have unique challenges since they serve a population that tends to be older, poorer and sicker than metropolitan area residents. Yet, they have the same fixed costs (e.g. salaries and capital expenditures) but smaller patient volumes to cover those costs. Balancing these competing demands can be difficult.

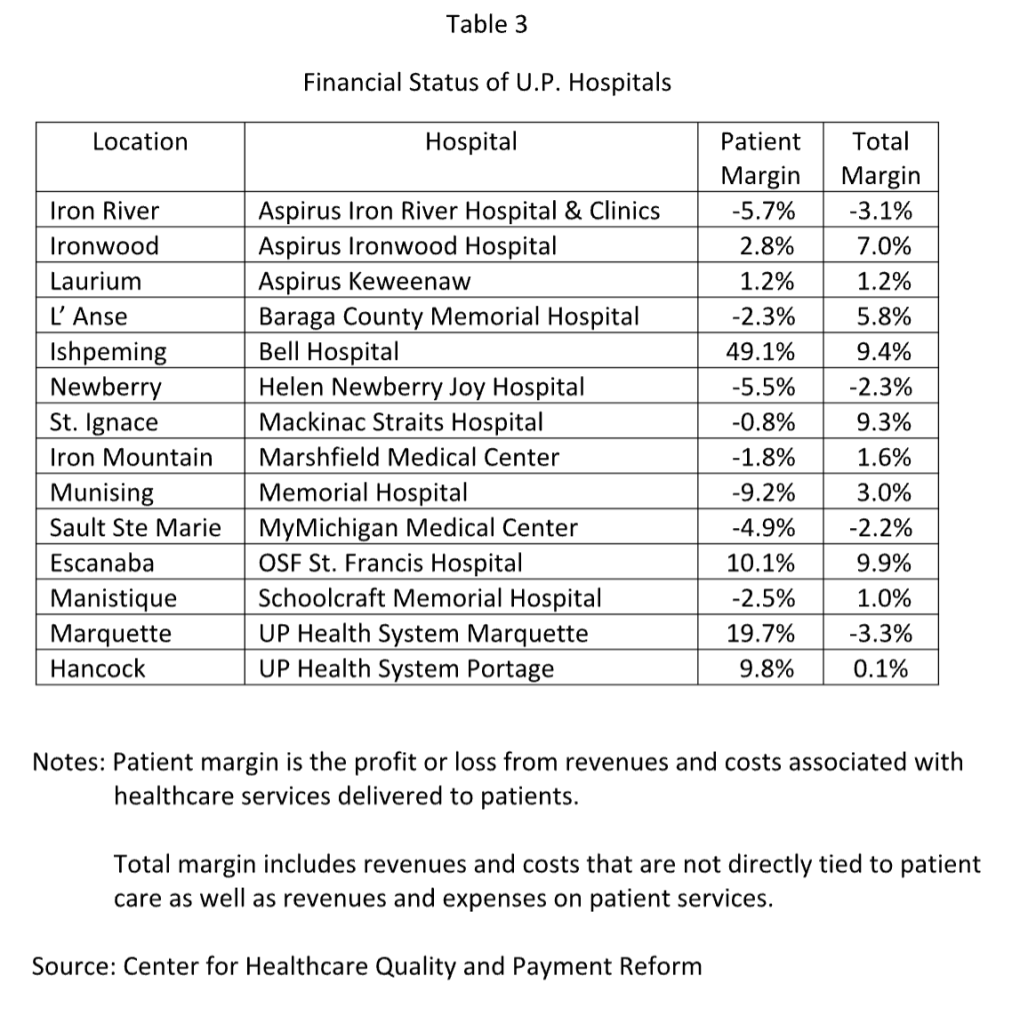

The Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform using data from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid has compiled a database on the financial status of rural hospitals. According to these data, four U.P. hospitals had negative operating margins in 2024 (Table 3).

The majority of hospitals have a positive total margin despite incurring losses on patient services because they receive local tax revenues or state grants that offset the losses. But moving forward, fewer patients with health insurance will likely increase the number of hospitals with negative operating margins.

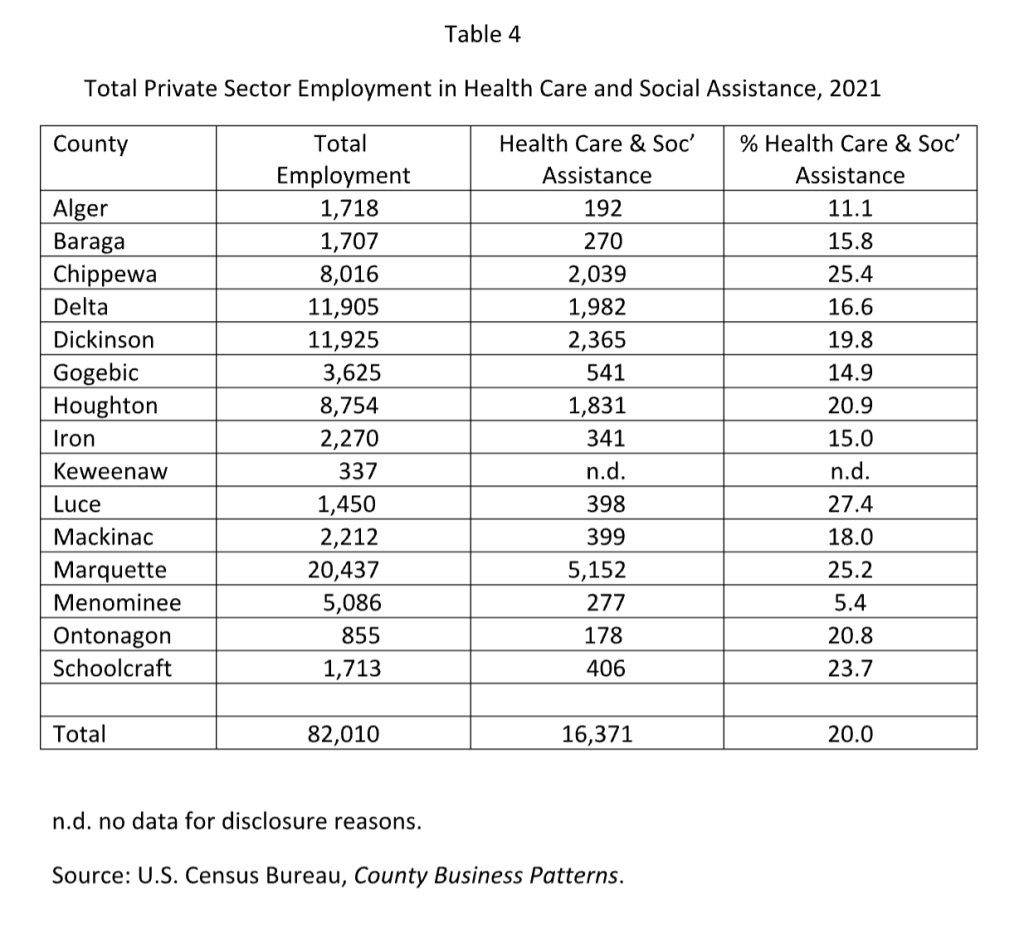

Healthcare is a major employer in the U.P., accounting for about 20 percent of total private sector employment (Table 4). Hospitals are often the major employer in a rural community; when they close or services are withdrawn to save money, it makes a community less attractive for outside investors. When Aspirus closed its Ontonagon Hospital in 2024, its Emergency Room was eliminated; it now operates a clinic at the site. Persons needing E.R. care now have to travel 47 miles to the nearest facility in Ironwood.

Conclusions

Cutting Medicaid funding is now enshrined into law. Accessing healthcare is already a challenge for U.P. residents given its sparse population and the necessity of traveling to larger centers where providers are located. Hospital officials are in general agreement that with less income they will have to cut services or shut down completely.

This paired with reductions in coverage, increased travel time and loss of employment for healthcare workers highlight the many challenges UP residents will confront in the light of this Big Beautiful Act; serving only to widen the existing gap in health outcomes between urban and rural Michigan.

This is what Trump said he was going to do and I guess we will all get what they voted for. I remember 40 years ago the Soo did not even have an OB/Gyn, you had to go to Canada (probably not now) or to Petoskey to get care. Backwards thinkers.

America has lost its sense of community. Our laws now bend and change to benefit billionaires and corporations. They’re all given tax cuts, while the working people who actually pays the taxes have their benefits stripped from them. Our current fascist authoritarian government is destroying everything this country once stood for.

It won’t be long before they start to come for our guns, so we have no way to resist.

A quick look at election results from 2024 shows that voters OVERWHELMINGLY decided to do this to themselves and their neighbors by who they elected.

Jack Bergman has the largest and poorest district in Michigan and he voted against his constituents best interests.

I’m positive losing more rural Healthcare will NOT

Make America Great Again…

Voters, you’ve been fooled AGAIN!

Interesting article. I will need to read it a couple of more times.

Excellent article. Thank you for your great work.

Right now I thank God that my Mom is dead… she was living in a nursing home on MEDICAID in Marquette County. She will never have to be categorized as Waste, Fraud, or Abuse.

“During his presidency and in recent discussions, Donald Trump has stated that he aims to cut only waste, fraud, and abuse from the Medicaid program. He has pledged to protect and improve Medicare and Medicaid, ensuring access to quality care free from such issues.”

I guess many would call Donald trump a bald faced LIAR. I am truly sorry for those who did not see through this con man liar. Now we all must live with these consequences….

Thank you for this objective factual reporting. I’m afraid the erosion of trust in government statistics and science promoted by the current administration will cause many people to dismiss this as “ fake news.”

……and now the rest of the story. First and foremost, there are no “cuts” in Medicaid benefits. The spending will grow annually in line with the growth of the economy…..approximately 3%. This will remain true even thought the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services estimates that improper payments over the past 10 years for able bodied adults exceeded half a trillion dollars and improper payments for just this past year exceeded 56 billion dollars. Those losing benefits include an estimated 4.8 million able-bodied adults, 2.2 million who did not qualify to receive benefits even before the BBB and 1.4 million illegal immigrants.

Pregnant mothers, disabled persons, caretakers of disabled persons, caretakers of children under 6 and persons with medical conditions that result in work limitations will continue to receive their benefits. There is a common sense requirement that requires able-bodied adults to “work” 20 hours a week (not excessive). This requirement may be met with regular paid work, work with a non-profit, volunteer work or educational activity (btw Michigan had a similar requirement that wasn’t enforced for several years and in January a bill was signed by the Governor eliminating the requirement).

Rural hospitals only comprise 7% of Medicaid spending. The BBB designates a 50 billion dollar rural hospital fund which will more than make up the funds they previously received from Medicaid for those who did not qualify to receive benefits.

No chicken little, the sky is not falling!

You blew it out of the water for me with .

This will remain true even thought the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services estimates that improper payments over the past 10 years for able bodied adults exceeded half a trillion dollars and improper payments for just this past year exceeded 56 billion dollars. Those losing benefits include an estimated 4.8 million able-bodied adults, 2.2 million who did not qualify to receive benefits even before the BBB and 1.4 million illegal immigrants.

Post facts. Medicade of Michigan is an income based health insurance program so the 2.2 million recipient’s are qualified under the Michigan Medicaid financial guideline’s a single person or a family must be at or below the poverty level criteria set by the State of Michigan. 1.4 million illegal immigrants really? illegal immigrants are not eligible for Medicaid service period in the State of Michigan. Hence they would not be turned away in an emergency situation at a hospital in Michigan. And yes perhaps many family’s may feel like the sky is falling.

Feel free to fact check me. Remember there are both state requirements and federal requirements to be eligible for Medicaid.. both must be met and that has always been the case.

Medicaid is a jointly funded federal and state program that provides health insurance coverage for many low-income children and adults, making it an important and powerful tool for improving the health of Michiganders.

In June 2024, over 2.6 million of Michigan’s 10 million residents were enrolled in Medicaid, 1.7 million adults and 946,314 children.i Most of Michigan’s Medicaid costs —over 65 percent in 2024—are paid for by the federal government.ii

States have considerable power to tailor Medicaid policy, benefits, and

services to address their residents’ health and social needs. In Michigan, both traditional Medicaid and the Healthy Michigan Plan (HMP) cover Michiganders. HMP provides coverage for individuals who became eligible through the Michigan Medicaid expansion, implemented in 2014.

This primer provides key information about Medicaid in Michigan, including:

• Medicaid financing: The program is jointly funded by the state and federal government, with $18.5 billion in federal contributions in FY24.

• Eligibility and benefits: Michigan Medicaid covers people with incomes up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level, providing a range of services like hospital visits, dentistry, behavioral health, and long-term care.

• Program challenges: Challenges that impact the program include costs and cost variation by beneficiary group, low provider reimbursement rates, and enrollment complexity.

Medicaid Program Overview Annual spending

The largest spending category in the Michigan state budget is for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS), which includes spending for Medicaid. At $37.7 billion, the MDHHS budget represents 45 percent of the total state budget in FY 2024-25. Within the MDHHS budget, the Medicaid program constitutes the largest category of annual spending, totaling approximately $24 billion. Of this, $18.5 billion is covered by the federal government, and $5.5 billion is state funding.iii

In FY 2025, the federal contribution to Michigan Medicaid, known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) or Medicaid matching rate, will cover 65.13 percent of the cost of coverage for traditional Medicaid, and 90 percent of the cost for those enrolled in the state’s Medicaid expansion plan, the Healthy Michigan Plan (HMP).1,iv Michigan state Medicaid funds primarily come from General Fund/General Purpose (GF/GP) revenue.

1 The FMAP is calculated using state per capita income. During the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, the FMAP was increased 6.2 percentage points to provide additional support for states to continuously enroll individuals in Medicaid throughout the Public Health Emergency. This enhanced FMAP ended December 2023.

Copyright @ 2024 by the Center for Health and Research Transformation

LEGISLATIVE BRIEF MedicaidinMichigan

Medicaid eligibility

Medicaid provides health insurance coverage for those in Michigan with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). In 2024, that is equivalent to an annual income of $20,783 per year for a single-person household and $35,632 per year for a family of three.v Certain individuals in special populations who earn more than the income limit may also qualify, including pregnant women, people with disabilities, and aging seniors receiving long-term services and supports (LTSS).vi

Prior to expanding Medicaid in Michigan, eligibility for Medicaid coverage for individuals making over 100 percent of the FPL was categorical. In other words, to qualify for Medicaid coverage, low-income Michigan residents earning more than the FPL had to fall into specific non-financial classifications (e.g., pregnant women; individuals with disabilities).vii

The relationship between poverty and health status is well documented; low-income individuals are more likely to have a higher burden of chronic disease and poorer health outcomes.viii A contributing factor to this disparity is access to healthcare, including health insurance coverage.ix

Flexibility

The federal government establishes certain eligibility and benefit requirements for Medicaid but leaves much flexibility to states to structure and implement their programs. xi This flexibility is available to states through Medicaid demonstration waivers or state plan amendments. With approval from the federal government, states that submit waivers and amendments can expand the scope of services offered through Medicaid as well as the populations they serve.xii Though these program levers are

powerful tools, they are also complicated to design and implement, and require detailed reporting and evaluation.

As of July 2024, Michigan has 10 approved Medicaid waivers implemented through Section 1115 or Section 1915 authority of the Social Security Act. These waivers serve a variety of functions, including:

• expanding Medicaid eligibility to Michiganders impacted by the Flint water crisis,

• providing additional community-based services for individuals with behavioral health needs,

• providing guidance for Medicaid managed care programs, and

• supporting home and community-based services.xiii

These waivers are time-limited and are generally approved for up

to five years. If a Medicaid program is successful under the

waiver authority, states may submit requests for extensions to the

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). In addition, all waivers must be formally evaluated for impact.

Benefits and services

Services covered by Medicaid can vary widely across states. However, federal guidelines do require all states to cover a minimum set of benefits and services.

Expansion of dental coverage for adults

Michigan significantly expanded dental coverage for adult Medicaid beneficiaries in April 2023. Increased access to dental services can help prevent and detect costly oral health diseases and related chronic conditions, reducing emergency room visits and lost work hours. These redesigned Medicaid dental benefits and increased provider payments cost $115.1 million in total state and federal funding for FY 23-24.12

Newly covered dental services include root canals and gum care, and the expansion significantly increased reimbursement rates for dental services to encourage more dentists to serve Medicaid patients. As of July 2024, however, long waitlists for dental care persist as there are still too few dentists accepting Medicaid patients.x

2

LEGISLATIVE BRIEF MedicaidinMichigan

Mandatory benefits

Mandatory benefits include but are not limited to inpatient and outpatient hospital care, laboratory services, ambulance services, family planning, and home health services. All children enrolled in Medicaid are eligible for the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit. EPSDT provides preventive care for children related to dental, mental health, and specialty services.xiv

Optional benefits

CMS also designates certain benefits as optional for states to cover.xv Michigan Medicaid covers many common optional benefits such as dental, vision, prescription drugs, and hospice care as well as less common benefits like chiropractic care and doula services.xvi In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Michigan, along with many others states, are choosing to enact benefit expansions to address behavioral health, maternal infant health, and social needs, such as food insecurity.xvii

Long-Term Services and Supports

Michigan, like most states, is working to support beneficiaries who prefer to age in their homes rather than in costly nursing homes. Medicaid is the primary funder for long-term services and supports (LTSS), which provide enhanced program coverage for individuals who require additional assistance with activities of daily living such as eating, bathing, and managing medications, as well as those who need much higher levels of care.xx

Examples of LTSS programs in Michigan include:

• the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE),

• the MI Choice waiver,

• Home Health benefits,

• Community Transition Services (CTS),

• MI Health Link, and

• Home Help.xxi

Enrollment in managed care

Michigan is a national leader in enrolling Medicaid beneficiaries in managed care plans, first introducing managed care into the state’s Medicaid program in 1996. In contrast to traditional fee-for-service models that pay providers for each service they deliver, managed care works to reduce health care costs and improve quality of care by paying providers a fixed amount per person (a “capitated” payment) for all of their care. This creates incentives for providers to reduce any unnecessary care and to keep patients as healthy as possible.xxii Two-thirds of Michigan Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in a managed care plan rather than receiving care on a fee-for-service basis.2

2 CHRT calculation based on the total number of individuals enrolled in managed care in Michigan and total number of Medicaid enrollees for June 2024.

Direct care workers in Michigan

Direct care workers (DCWs) provide long-term care services to vulnerable populations—largely older adults and people with disabilities—and often help keep people in their homes. Many Medicaid funded long-term care services are provided by DCWs. According to the 2024 Michigan Healthcare Workforce Index, Michigan’s home health aides, personal care aides and nursing assistants have some of the highest shortage levels and turnover rates of all healthcare workers in the state.xviii

Strategies to support DCWs in other states include wage and benefit increases, employment benefits, recruitment and retention bonuses, and more. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Michigan legislature enacted three wage increases for DCWs. This continued in FY24, resulting in a $3.20 per hour wage increase from October 1, 2023 to September 30, 2024.xix

3

LEGISLATIVE BRIEF MedicaidinMichigan

As of June 2024, nine Medicaid Health Plans (MHPs) provide managed care for nearly 1.8 million Medicaid enrollees across the state (none of the MHPs serve the entire state). MHPs receive a capitated payment for each enrolled beneficiary, assuming full financial risk for care and services provided for their enrollees.xxiii This arrangement can save Medicaid program costs for the state and incentivize MHPs to provide appropriate, preventive, high-quality care for beneficiaries. It also encourages MHPs to cover additional evidence-based benefits and services beyond what the state and CMS require.xxiv

Behavioral health

Michigan is one of seven state Medicaid programs that “carves out” behavioral health (BH) benefits for beneficiaries with moderate to severe BH needs, and for those with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD).xxvi Most of those with mild to moderate BH conditions receive BH coverage under the same Medicaid managed care benefit that covers all their physical care services. Those with moderate to severe BH conditions and those with I/DD, however, receive coverage through a separate funding mechanism for more specialized BH services. This separate mechanism is administered through 10 prepaid inpatient health plans (PIHPs) across the state that fund the mental health, substance use, and disability services for the “carve out” population through a capitated funding arrangement. In recent years there have been unsuccessful efforts to “carve in” the Medicaid benefit for those with moderate to severe BH needs, xxvii with Medicaid health plans generally favoring a “carve in” and behavioral health advocates generally opposed to the change.xxviii

Impact of the Affordable Care Act

In 2014, Michigan expanded Medicaid coverage in the state through the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA). The expansion, known as the Healthy Michigan Plan (HMP), was made possible through a Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waiver, Medicaid state plan amendment, and Michigan Public Act 107 of 2013.xxix A Supreme Court ruling in 2012 provided states with the option to expand their Medicaid coverage rather than requiring states to expand as a condition for receiving federal funding.xxx Michigan was one of the national leaders in Medicaid expansion, implementing the expansion just three months after the authority began. As of June 2024, 41 states including the District of Columbia have expanded Medicaid coverage.

Michigan’s Behavioral Health Landscape

About six million Michiganders live in Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas, with areas of Northern Lower Michigan and the Upper Peninsula particularly impacted. The state would require an estimated 249 more psychiatrists to alleviate these shortage designations. Provider shortages are particularly acute for children: rates of child behavioral health (BH) conditions are rising while suicide rates fluctuate. Many of those seeking BH services endure long waits for outpatient appointments and in emergency departments (“ED boarding”). Options for improving access to behavioral health care in Michigan include supporting reimbursement for BH telehealth in Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance, BH provider loan repayment programs, and streamlined licensure processes through interstate licensing contracts.

From the Institute of Public Policy and Social Research

MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY

Veteran

The public health provisions in the massive spending package that President Donald Trump signed into law on July 4, 2025, will reduce Medicaid spending by more than US$1 trillion over a decade and result in an estimated 11.8 million people losing health insurance coverage.

As researchers studying rural health and health policy, we anticipate that these reductions in Medicaid spending, along with changes to the Affordable Care Act, will disproportionately affect the 66 million people living in rural America – nearly 1 in 5 Americans.

People who live in rural areas are more likely to have health insurance through Medicaid and are at greater risk of losing that coverage. We expect that the changes brought about by this new law will lead to a rise in unpaid care that hospitals will have to provide. As a result, small, local hospitals will have to make tough decisions that include changing or eliminating services, laying off staff and delaying the purchase of new equipment. Many rural hospitals will have to reduce their services or possibly close their doors altogether.

Hits to rural health

The budget legislation’s biggest effect on rural America comes from changes to the Medicaid program, which represent the largest federal rollback of health insurance coverage in the U.S. to date.

First, the legislation changes how states can finance their share of the Medicaid program by restricting where funds states use to support their Medicaid programs can come from. This bill limits how states can tax and charge fees to hospitals, managed care organizations and other health care providers, and how they can use such taxes and fees in the future to pay higher rates to providers under Medicaid. These limitations will reduce payments to rural hospitals that depend upon Medicaid to keep their doors open.

OK MAGA explain this to you neighbors family and friends how the next hospital that could face closing maybe Aspirus Ironwood.

And boy did you cut everyones throat when you voted Trump!! The laughs truly on you your families your grandchildren. You truly. have proved that ignorance is definitely not an admirable trait!

The critical access hospital in Ontonagon, just 50 miles from my hometown in the Upper Peninsula, closed last year.

The nearest emergency room is now a 45-mile drive away — nearly an hour in good weather. In a February snowstorm, that delay can mean the difference between life and death.

Most people hope never to visit an emergency room. But US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data shows that nearly 140 million Americans annually utilize ER care, often during the most vulnerable moments of their lives. It’s often taken for granted that emergency rooms will always be there for us, but that assumption is increasingly at risk.

I’m an emergency room doctor, and I can tell you firsthand that ERs are the backbone of our country’s health care safety net. If HR 1 becomes law, based on a report from the Congressional Budget Office, we can expect millions to lose their Medicaid coverage. This will add to the rolls of the uninsured, placing a larger burden on already stressed hospitals and emergency departments. This means that more hospitals will likely close.Six hospitals in Michigan are at imminent risk of closure, a recent study by the Centers for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform found, while 14 more are at risk of closure over time ― roughly 31% of rural hospitals in Michigan, and 12% of all hospitals in the state. That’s before any impact of these proposed cuts which the passed the U.S. House of Representatives by a single vote, largely along party lines.

Hospitals already operate on razor-thin margins, and anything that disrupts the funding makes those margins even tighter.

Losing billions in Medicaid funding could push many hospitals over the edge.

Hospitals rely on Medicaid

In Michigan, the numbers are stark: one in five adult residents rely on Medicaid for health care.

Among children, that number increases to two out of every five. Medicaid also covers 38% of all births in the state. Medicaid isn’t a fringe benefit for the few — it’s a critical lifeline for millions.

And it’s a key part of the financial foundation for hospitals that serve our most at-risk communities.

But that foundation is crumbling.

A recent report by the RAND Corporation confirms what frontline physicians already know: America’s emergency care system is in crisis, and emergency rooms throughout the country are strained to, or even beyond, their breaking point.

Declining Medicare reimbursements, shrinking insurance payments and threats to Medicaid funding are converging to further endanger access to emergency care.

Currently, 20% of the care provided by emergency rooms in the U.S. is uncompensated, comprising an annual price tag of over $5 billion. This is unsustainable.

With further cuts to Medicaid, it is possible that 22 Michigan communities could soon be left without a hospital — and without the lifesaving emergency care we all depend on.

And it’s not just patients on Medicaid who stand to lose. When hospitals close, everyone suffers — whether they’re covered by private insurance, Medicare or Medicaid. The collapse of emergency infrastructure in any region puts pressure on surrounding hospitals, increases wait times and reduces the overall capacity of our system to respond in times of crisis.

Doctors rely on functioning hospitals

Emergency physicians like myself are proud to care for anyone who walks through our doors — 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. We are required by federal law to treat all comers, regardless of their ability to pay.But we cannot do it alone. We rely on functioning hospitals, adequate funding and a health care system that values access for all.

If we continue to underfund Medicaid — or treat it as expendable — we risk eroding the structure that holds our emergency care system together.

This isn’t just a policy debate. It’s a matter of access to health care. It can become a matter of life and death.

Now is the time to ensure the viability of the emergency medical system in our state. We should take steps to protect and strengthen the programs that support emergency care — not dismantle them. When your life is on the line, you shouldn’t have to wonder whether help will be there when you need it.

Brad J. Uren is an emergency room doctor, a past president of the Michigan College of Emergency Physicians and vice chair of the board of directors of the Michigan State Medical Society.

Fact Check -Dick Wendt Comments

1. “First and foremost, there are no ‘cuts’ in Medicaid benefits. The spending will grow annually in line with the growth of the economy — approximately 3%.

This is **unsupported**. Medicaid spending is driven by enrollment and medical inflation, not just economic growth. In fact, legislation projects federal Medicaid spending reductions of nearly **\$911 billion over ten years**. A flat 3% growth claim does not align with authoritative forecasts.

**2. “CMS estimates that improper payments over the past 10 years for able-bodied adults exceeded half a trillion dollars and improper payments for just this past year exceeded \$56 billion.”**

This is **misleading**. CMS reported an **improper payment rate of 5.09% in FY 2024**, equal to **\$31.1 billion**, not \$56B. The decade-long \$543B figure refers to **all Medicaid improper payments**, not only for able-bodied adults.

👉 **Clarification:** An *improper payment* does **not always mean fraud or abuse**. It is any payment that should not have been made or that was made in the wrong amount. This can include:

* Payments without sufficient documentation

* Payments made to ineligible providers or beneficiaries

* Payments for services not covered

* Overpayments or underpayments due to administrative or reporting errors

Most improper payments are due to **paperwork or eligibility errors**, not intentional fraud. The claim both inflates and misattributes the totals.

**3. “Those losing benefits include an estimated 4.8 million able-bodied adults, 2.2 million who did not qualify even before the BBB, and 1.4 million illegal immigrants.”**

This is **false and misleading**. Federal law **prohibits Medicaid funding for undocumented immigrants**, except for limited “emergency Medicaid” services such as emergency room care and labor and delivery. No federal dollars go to cover full Medicaid benefits for undocumented individuals. The claim that 1.4 million “illegal immigrants” are losing benefits is **not supported by evidence** and misrepresents how Medicaid works.

👉 **Clarification:** The term *able-bodied adults* is also often misused. Research shows that the majority of Medicaid enrollees who fall into this category are actually **working poor** — employed in low-wage, unstable, or part-time jobs that don’t provide health insurance. Others are caregivers, students, or have undiagnosed health limitations. So framing them simply as “non-working” is inaccurate.

This is **false and misleading**. Federal law **prohibits Medicaid funding for undocumented immigrants**, except for limited “emergency Medicaid” services such as emergency room care and labor and delivery. No federal dollars go to cover full Medicaid benefits for undocumented individuals. The claim that 1.4 million “illegal immigrants” are losing benefits is **not supported by evidence** and misrepresents how Medicaid works.

**4. “Pregnant mothers, disabled persons, caretakers of disabled persons, caretakers of children under 6, and persons with medical conditions that result in work limitations will continue to receive their benefits.”**

This is **generally true**. Vulnerable groups are typically exempt from work requirements or cuts. However, the scope and protections depend on specific legislation, so details may vary.

**5. “There is a common-sense requirement that requires able-bodied adults to ‘work’ 20 hours a week… (Michigan eliminated the requirement in January).”**

This is **partially accurate**. Work requirements have been part of some state Medicaid waivers, including Michigan’s Healthy Michigan Plan. They often allowed work, volunteering, or education to qualify. In January 2025, **Michigan repealed its Medicaid work requirement**.

**6. “Rural hospitals only comprise 7% of Medicaid spending. The BBB designates a \$50 billion rural hospital fund which will more than make up the funds they previously received.”**

This is **partially true**. The reconciliation bill includes a **\$50 billion Rural Health Fund (2026–2030)**. However, nonpartisan analysis shows it would offset only about **37%** of rural Medicaid funding cuts, not “make up” the full losses.

**7. “No chicken little, the sky is not falling!”**

This is **opinion**, not a factual claim.

—

Bob, thank you for verifying everything I said except where you counter with what is solely your own opinion. I assume you have read the BBB. The bottom line is that those that truly need Medicaid and qualify will continue to receive benefits. Best, Dick Wendt

HEY MR WENDT??

What just happened to the hospital in Ironwood Michigan???

Birthing unit closing in 2 plus months “YOU” told all of us here there was PLENTY OF MONEY TO SUPPORT ASPIRUS , IRONWOOD and hospitals in UP.

Well Dick Wendt this chicken little has just laid an egg on you, and it’s all over your face.

Just remember the expert Dick Wendt told you it was all good????

Might not want to be driving to close to the man, giving his lack of judgement, my fellow yoppers!

You’ve Been Had!

Hello Mr Dick Wendt??

I find this man nothing but a truly bloviating air bag.

Again Aspirus Ironwood will close Birthing unit and OB GYN services as of January 1, 2025.

That’s a fact, that’s a Result of MAGA supporters.

You can run and hide…but I’m calling you out here again.

WTF, just happened you assured us in your previous writings/ramblings that all was well “and we warned it was not”

And all we hear now is crickets from Dick Wendt????

You sir are nothing more than a fraud here.

And a lot of people need to hear that, with all your rambling distortions and SELF proclaimed facts

Nothing more than your unsupported lies

“THE EVIDENCE IS IN!”

– ASPIRUS IRONWOOD HAS CLOSED THE 1ST DEPARTMENT AND SERVICE TOO WESTERN UP-

WITH A VERY GOOD CHANCE OF SAME HOSPITAL CLOSING SERVICES ENTIRELY.

Yea Dick Wendt , were the misinformed? Were the chicken littles as you called us!?

“MR DICK WENDT”

Honestly Folks we really need to call this out here or just be another casualty of the DICK WENDTS/MAGA theives and liars gutting America and UP Michigan small towns.

At our expense and our childrens futures, right before are own eyes.

Hey Dick we know where the bear sh_ts in the woods, and who the bear is ….Lol

Anyone hear crickets?

Latest News Aspirus Houghton Hancock,

Has now officially closed its Birthing/OBGYN hospital services!!!

Again this Chicken Little as Mr Dick Wendt loves to call us lefties that he’s so proud to own.

We were right on when we warned you all of the consequences you/ your neighbors/ and family will be raining on your own heads.

Yea you sure owned us in the 2024 election, and now you own nothing not even health care.

One more question here where the hell are all these Maga geniuses????

No comment???

Hey Dick Wendt tell me what a fool I was????

I hear crickets….Lol

NO KINGS (TRUMP) ANTI-MAGA PROTESTS OCTOBER 18 SATURDAY 2025

ere’s a Real Idea for “ALL YOOPERS TO PARTICIPATE IN”

Why don’t we all start relating the prices were being met with at grocery stores, gas stations, health care costs, Wal-Mart.

A trip out for dinner and post it right here for all of us, to share with one another the “Real realities of Americans just trying to get bye in what Trump says is the Greatest Economy Ever!

Let me be the first to start here Maxwell House Coffee in the big blue plastic container.

Just bought same coffee I’ve been buying for around 10.00$ recently now at 19.00 $.

Now this can be real journalism from the people and for the people and we may be able to save a fellow Yoopers kids from going hungry if we can point to deals!

And the second and most important reality “WE CAN ALL RELATE TO THE PAIN THAT TRUMP AND HIS MAGA SUPPORTERS CLAIM IS GREAT FOR ALL OF US???

So please feel free to post grocery costs for yourselves and your families, thats a hard reality we can all and we all see every day that we know are the real story fo the Gutting of hard working middle class Americans.

And yes is what real democracy and facts look like, so lets all get out of the boot licking boxes we all gravitate too whether Democrats or Republican.

WE HONEST MIDDLE CLASS FOLKS CALL THIS FACTS!

God bless you participation