The Upper Peninsula’s Food Price Premium

Anyone who shops regularly for grocery items knows how prices have soared over the past year. The US Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service estimates that retail food prices increased 8.9% for the first seven months of 2022, compared with 1.9% for the equivalent period in 2021.

Egg prices are up over 20% from 2021, largely as a result of an outbreak of Avian flu among commercial poultry flocks that led to a culling of over 28 million laying hens. The war in the Ukraine boosted wheat prices and the cost of bread, as the country’s wheat exports were curtailed.

Labor shortages in trucking and other sectors have led to wage and benefit increases to attract workers, with companies electing to pass on those added costs to customers. At the same time average gas prices in the US are up 20% from October 2021, adding to the cost of shipping goods.

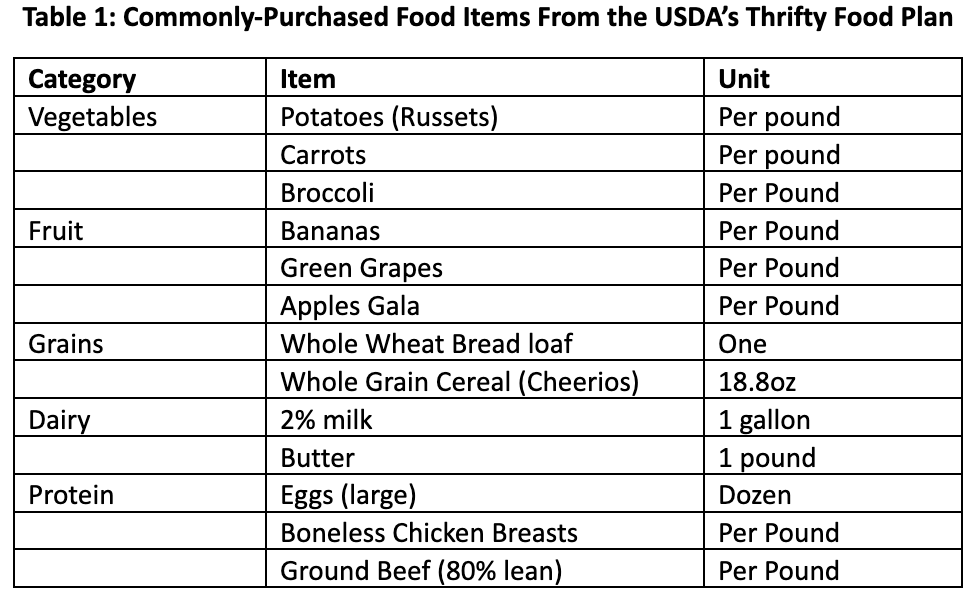

For Upper Peninsula residents, higher food and gas prices are part of the cost of living in a remote area and the latest food price increases have only added to those costs. This article illustrates the added price premium that UP residents in remote areas pay for basic food items by examining the total cost of 13 commonly-purchased food items from the US Department of Agriculture’s Thrifty Food Plan (Table 1) and considers recent changes in the availability of fresh food with the growth of Dollar Stores.

The price data were collected between September 19-24, when visits were made to locally-owned grocery stores in Baraga (2020 pop. 1,883), Gwinn (2020 pop. 1,741), Ishpeming (2020 pop. 6,433) and a national supermarket in Marquette (2020 pop. 20,631). For ease of comparison, no sale prices were included in the data.

The total costs for the thirteen items were $36.07 in Marquette, $44.97 in Ishpeming, $50.56 in Gwinn, and $51.38 in Baraga. In contrast, the same items purchased online at a national supermarket in Lansing amounted to $34.60 (this total does not include a delivery charge). Baraga, situated about 70 miles northwest of Marquette and 28 miles south of Houghton, is the most ‘isolated’ of the four communities and, not surprisingly, its total food bill was 42 percent higher than Marquette’s. In fact, the farther the distance from Marquette the higher the total food cost.

A national supermarket chain can purchase bulk quantities of food, and lower prices through so-called economies of scale. In contrast, grocery stores in smaller communities are hampered by lower sales volumes and are thus unable to pass on any savings from bulk purchases to their customers, while the added transportation costs involved in shipping smaller volumes have to be included in the sale price of items.

Wal-Mart, from its earliest days, perfected the art of lowering prices to a point where it was able to earn more from a cheaper retail price than it could by selling the item at a higher price simply by increasing the sales volume. This business model is not without its critics, with studies showing that when Wal-Mart comes to a community it drives out smaller locally-owned businesses, while paying its workers low wages and providing few benefits.

At the same time, large supermarket chains are seen as supporting a system of industrialized agriculture that promotes monoculture (the cultivation of a single crop) and is only made possible by the heavy use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides. These chemicals end up polluting the environment and exposing farm workers to toxic chemicals.

The lower food prices that national and regional supermarkets charge for basic food items compared with locally-owned grocery stores means some consumers in rural areas often end up driving long distances to regional shopping centers in search of lower prices. This, in turn, negatively affects grocery sales in locally-owned stores and results in store closures.

Between 2012 and 2020, US census data indicate that the number of grocery stores in Delta (Escanaba), Dickinson (Iron Mountain), Chippewa (Sault Ste Marie) and Marquette counties dropped from 60 to 51, a 15% decline. In the city of Marquette, Valle’s Village Market on north Third Street, a grocery store that served a local neighborhood and nearby NMU students, closed in 2018. Its owner attributed his decision to shutter the store and lay off 20 people to lower sales caused by the opening of a Meijer’s supermarket in the adjacent township.

Unfortunately, due to census data disclosure restrictions, it is impossible to determine whether this phenomenon exists in UP counties with smaller populations.

While traditional grocery stores are going out of business, the region has seen an increase in the number of so-called Dollar stores (e.g. Dollar General, Family Dollar, and Dollar Tree). There are seven such stores in Marquette County and two in Baraga County. These stores, in addition to stocking basic household items, also sell food. However, they rarely sell fresh vegetables or fruits, and apart from basic items such as milk, eggs, butter and bread, most food is either canned or highly processed.

These stores lure customers on the premise of affordability but don’t always deliver. For example, one Dollar store sells Cheerios cereal in 3.5 oz packages for $1.25, but a customer has to make a minimum purchase of six packs, making the actual cost/ounce more expensive than most grocery stores’ price for a single 18-ounce box of Cheerios. Studies show that when these stores open in small communities, they typically cut sales at locally-owned supermarkets by about 30%, while the jobs they create are low paying and employ fewer people than the grocery stores they replace.

There are no quick fixes to higher food prices in remote rural areas or increasing the availability of affordable fresh food options. Its causes are complex and lie outside the Upper Peninsula, while geography and economics inevitably mean higher food prices regardless of outside circumstances.

What is apparent is that rising food prices favor larger chains who can offer comparatively lower prices than locally-owned competitors. Furthermore, higher food prices constrain people’s ability to make healthy food choices, which increases the likelihood that they will fill up on highly processed foods, increasing the likelihood of long-term health risks.

Very concise well written article. Thank You.

Great topic – research and focused on the whys and hoe comes.

I live in far eastern Chippewa County, we have a small store nearby, the owners have to go and purchase many of the grocery items they carry, no delivery available. Jilberts Dairy has stopped delivery to the small stores in our area and if the store wants dairy products they have to drive and get them. The rural food supply chain has been broken here by the Wal Marts and Meijers. As a farmer who has grown food for my community, the access to processing and markets is as broken as the supply side problems small store owners face. Our area has the opportunity to choose a better food system, but it will require planning and investment if we want to have access to good quality food in the UP.

The UP has the ingredients to build a sustainable food system, to get out of the rural food desert cycle. Our farmers provide fresh vegetables and humanely raised meat at the local level. The barriers to this system are price and access. One small project is trying to overcome those barriers by connecting local residents to local farmers, providing weekly boxes of fresh food. Farms for Folks in Alger County depends on donations to cover farm and transportation cost, but slowly bringing the project to scale is the hope. Cutting out the middle of the gigantic food system—monoculture farms at a distance, expensive and fuel-intensive transportation, processed foods instead of fresh foods—has to become a local, rural solution.

Farms For Folks is based on need and includes an application process. Recipes are included with the boxes because not everyone, or shall I say no one, knows what to do with kale. The deliveries are by volunteers who form a relationship with the participants, an added community builder.

I tried to join the Misfits Market system – they distribute “less than grocery store perfect” produce, etc., via UPS – much organic, selection sometimes limited, etc. but less expensive than even big box stores – (they “don’t serve Hessel” but they accepted a change of address for daughter in McMillan to Hessel). I wonder if they could be recruited into a new system to improve UP supply?

Great information to help understand the challenges. It would be nice to have a UP coalition to find ways to get local products to local people across the whole UP and find ways to solve the problems.

I’m not a fan of dollar stores, but they do sell plenty of nutritious food which is not highly processed, including a variety of canned beans, vegetables, and fruits as well as kitchen staples such as rice and pasta. The ones I go to also always have an assortment of milk and cheeses in their refrigerated cases. I won’t pretend for a minute that a serving of canned spinach is as tasty as a good salad, but it’s as least as healthy. Consumer Reports has also established that overall, they are indeed less expensive than alternative outlets. https://www.consumerreports.org/dollar-stores/the-truth-about-those-dollar-stores/