Christmas Comes to the Upper Peninsula

The observance of Christmas in the Upper Peninsula is a remarkable 361-year chronicle of transformation. It was first introduced by the French Canadian Jesuit missionaries and settlers. This was counterbalanced by the Yankees, whose ancestors had questions about Christmas and overindulgence during the holiday, arriving in the 1840s. Coming along with them were French Canadian, German, Irish, Cornish immigrants who brought with them a return to the celebration of the season. By the early twentieth century we see the elements of our present celebration of the holiday.

It was Jesuit father René Menard who spent the winter on the shore of Keweenaw Bay at L’Anse who first commemorated the day among the Odawa in 1660. The Jesuits Jacques Marquette and Louis Nicolas established St. Mary Mission at Sault Ste. Marie in 1668 and celebrated the day. Three years later the St. Ignace mission was founded and then the nearby mission of St. Francis Borgia was established. Jean Enjalran, SJ has left us with an account of the well-developed Christmas celebration in the late 1670s. The Catholic Hurons had developed a deep reverence for the mystery of the birth of Christ. Weeks in advance they started their plans for a solemn commemoration. A grotto became a creche which was lined with grasses and a statue of the Infant placed in it before which people prayed. The community attended midnight Mass. Then on the feast of the Epiphany (January 6) when the “three great stranger Captains” visited Christ, a grand procession was held and three elders dressed in finery representing the Magi and brought porcelain presents to the Infant. The Huron and Odawa held numerous dances and feasts as part of the celebration.

We are privileged to have the reminiscences of Elizabeth Thèrése Baird who grew up on Mackinac Island in the 1820s. The folks on the island were mostly Catholic without a resident priest. What follows is her fine insights into the celebration of Christmas:

“The Catholic faith prevailing, it followed as a matter of course that the special holidays of the church were always observed in a memorable, pleasant manner, in one’s own family, in which some friends and neighbors would participate. Some weeks before Christmas, the denizens of the Island met in turn at each other’s homes, and read the prayers, chanted psalms. And unfailingly repeated the litany of the Saints. On Christmas eve, both sexes would read and sing, the service lasting till midnight. After this, a réveillon (midnight treat) would be partaken of by all. The last meeting of this sort which I attended, was at our own home, in 1823. This affair was considered the high feast of the season, and no pains were spared to make the accompanying meal as good as the Island afforded. The cooking was done at an open fire. I wish I could remember in full the bill of fare; however, I will give all that I recall. We will begin with the roast pig; roast goose; chicken pie; round of beef, à la mode; pattes d’ours (bear’s paws, called so from the shape, and made of chopped meat in crust, corresponding to rissoles)l; sausage; head-cheese; souse; small-fruit preserves; small cakes. Such was the array. No one was expected to take of every dish, unless he chose. Christmas was observed as a holy-day. The children were kept at home, and from play, until nearly night-time, when they would be allowed to run out and bid their friends a ‘Merry Christmas,’ spending the evening, however, at home with the family, the service of prayer and song being observed as before mentioned. All would sing; there was no particular master, — it was the sentiment, that was so pleasing to us; the music we did not care so much for.

“As soon as la féte de Nöel, or Christmas-tide, had passed , all the young people were set at work to prepare for New Year’s. Christmas was not the day to give and receive presents; this was reserved for New Year’s. On the eve of that day, great preparations were made by a certain class of elderly men, usually fishermen, who went from house to house in grotesque dress, singing and dancing. Following this they would receive gifts. Their song was often quite terrifying to little girls, as the gift asked for in the song was la fille aînée, the eldest daughter. The song ran thus:

Good day, master and mistress,

And everyone goes along.

So you don’t want to give us anything, tell us;

We only ask you the eldest daughter.1

As they were expected, everyone was prepared to receive them. This ended the last day of the year. After evening prayer in the family, the children would retire early. At the dawn of the New Year, each child would go to the bedside of its parents to receive their benediction — a most beautiful custom. My sympathies always went out to children who had no parents near . . . .”

In 1830 New Year’s Day was celebrated at Sault Ste. Marie with Ojibwe, metís and French made calls on the villagers and received “cakes, kisses, and whiskey” as gifts. This tradition continued in many UP communities well into the twentieth century.

In the early days of UP life, Christmas was little celebrated except by the Catholic population. The English had long celebrated the twelve days of Christmas – December 25 to January 6 – but with the coming of the Reformation many reformed churches concluded that this was unchristian to celebrate the days with mirth as was conducted in the UP. On December 23, 1758 mince Christmas Pye “enjoyed by all” was discussed in the New York Gazette. However it was reported that Quakers considered the pie “an invention of the Scarlet Whore of Babylon, Popery, the Devil and all his works.” The Boston Evening Post wrote “the birth of the Saviour of mankind is most worthy our notice” but was the reporter was concerned about “licentiousness, the idleness and intemperance that has for a considerable time has prevailed at this season.” This attitudes entered the UP in the 1840s. Change would take a while.

The development of modern Christmas had its origins in Victorian England where Prince Albert, a German and consort of Queen Victoria introduced the decorated Christmas tree which was followed by a celebratory connection with Christmas. On December 19, 1843 Charles Dickens published A Christmas Carol which immediately sold out. It influenced the modern Western observance of Christmas which include: family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, games and festive generosity of spirit.

A teacher Henry Hobart provides us with insights to the Christmas celebration at Cliffs Mine in 1862. Classes at school were closed for four days. The miners, mostly Cornishmen, went from house to house caroling for which they received mugs of ale. As a result liquor and ale were freely flowing. The local Episcopal church was decorated for the Festival and the “respectable families” celebrated at Brockway’s Hotel in Eagle River.

On June 28, 1870 President Ulysses S. Grant signed a bill designating Christmas a legal holiday for federal employees in the District of Columbia. It had widespread appeal and there was no discussion of a church vs state issue in Congress. The holiday spread throughout the states when urbanization and industrialization and the recent horrors of the Civil War made people feel uneasy.

This event brought about renewed change. In 1871 Catholic churches celebrated three Masses, Episcopalians and Lutherans, many of whom of the latter were Germans who had brought with them a strong tradition of Yule celebration had special services. However, most of the other denominations rejected Christmas in its religious form as a “human invention” of the papists. If it was kept it was merely as a social holiday but as the Escanaba newspaper wrote in 1874, “Christmas is the only day of the year concerned purely with joy.” Suddenly Christmas short stories and histories of the origins of Christmas began to appear in newspapers along with lengthy histories of the development of the holiday.

By the end of the century the celebration of Christmas was firmly in place. Christmas church services of all denominations included special sermons, musical programs with cantatas sung along with recitations and plays by Sunday school children. By 1911 several companies of carol singers were on the streets of Calumet visiting businesses reviving a quaint old Cornish custom.

TRAVEL

People from afar traveled to be with family during the holiday season. Students came home from college and school teachers returned to their homes away from the UP. In 1914 the South Shore Railroad offered low excursion fares for the holidays between December 18 and January 10 to as far as eastern Canada. Other railroads and trolley lines had similar reduced fares and extended service. Some railroads encouraged people to write to friends to come to the UP during the holidays.

GIFTS IN THE PAST

In the early 19th century French Canadians and Native Americans sought “cakes, sweets, provisions and a cup of whiskey” during the holiday season on New Year’s Day. The UP newspapers of the 1860s and 1870s had no ads promoting goods to be bought as gifts for the holiday. The idea was to provide gifts that were “good and useful” and could be used during the coming year. In 1875 at Escanaba shoe strings, ladies switches and “other articles of dress which modesty forbid us to mention were on vogue. Oysters, cigars, soap, cologne, jewelry, and bread are suggested. In 1887 gifts that were considered appropriate the long lasting included as “fine cut glass bottle of perfume” for a woman and a box of cuffs and collars for a man along with a compact toilet set for travel. There was always the box of cigar or a jar of tobacco. Books and magazine were also in order along with rocking chairs for girls. All ads were very low key. For kids by 1890 presents could include candy bags, dolls and “other nice things.” Department stores promoted their Toylands with the major attraction: “Santa Claus Is Here. A Real Live Santa!” and kids could select from tops, games, dolls and their beds, toy stoves, toy telephones, and rubber dolls. Later snowshoes, razors, flexible flyers, and skates were promoted. In 1912 the Bee Hive Shoe Store in Calumet advertised as Christmas gifts “a pair of shoes, a nice pair of slippers and a good pair of rubbers” as “they will be appreciated.” In 1913 Gately & Wiggins with stores in Ishpeming, Iron Mountain, Calumet, Houghton promoted the idea of giving furniture – “The truly acceptable Christmas present most be an abiding sort, not merely for Christmas Day but for every day.” The Hosking Electric Company in Calumet promoted the idea to “Make It an Electric Christmas” and give a washer and wringer, iron toaster, table lamp, heating pad, coffee percolator or a chafing dish. A box of chocolates was always a favorite.

THE POOR

From the 19th century forward even if Christmas was not elaborately celebrated there was a concern for the poor. In 1871 “the poor at Christmas” at Escanaba were a concern. Later the Elks Club in Sault Ste. Marie provided dinners to over 300 poor kids along with presents. From the 1890s the Salvation Army had bell ringers on street corners collecting money to feed the hungry. The Red Cross promoted Christmas seals to combat tuberculosis.

RECREATION FOR THE HOLIDAY

In 1854, sleighing was promoted as good at the Soo in and about town, but don’t venture into the woods. Also traveling along the snowy streets were “dashing cutters,” Yankee sleighs, French trains and dog teams with the idea being to get out and move about fast to deter the cold! In 1895 the Soo Gun Club had a turkey shoot on Christmas day. You brought your own rifle and the turkeys were placed at a reasonable distance for this “sport.” These shoots became popular. Athletic clubs promoted basketball, bowling, indoor baseball, and hockey and some of the church clubs included a cross-country run “if the weather permitted.” College hockey players provided excitement at the rink. By the 1900 dancing parties at halls were popular and attracted college students who were home for the holiday. With the arrival of movies provided special showing of holiday films and there was vaudeville. For relaxation there was always Christmas Beer from Bosch Brewing Company in the Copper Country.

FOOD AT CHRISTMAS

The various immigrant groups that arrived in the Upper Peninsula brought them their traditional activities to celebrate the day. Finnish immigrants celebrated Pikkujoulä/Little Christmas in mid-December at Lutheran church halls or fraternal organizations. It was an informal, highly festive occasion. At this time Christmas dishes are served for the first time. The buffet meal consisted of ham, lutefisk, sausage, potatoes and vegetables, Finnish bread and the long table was filled with Finnish delights beginning with traditional rice pudding along with fruit soup and a large variety of homemade pastries. The most traditional drink was mulled wine. The entertainment consisted of festive speeches, jokes, Christmas songs sung in Finnish and English, and then the arrival of Santa Claus/Joulupukki with gifts for the children. The Norwegians immigrants had a similar event called Julebord with pork ribs, lamb, spicy sausage, lutfisk, sour cabbage, brussels sprouts and lingonberry jam topped off with glögg or beer.

Finnish immigrants would also have a dinner either on Christmas Eve or the following day. The traditional menu consisted of beef broth; a tray of pickled fish, cheeses, breads, cold cuts; potato and rutabaga casseroles, beef salad, holiday lutefisk with white sauce; and desserts: creamed rice spiced with cinnamon and stewed prunes with whipped cream.

The Finns, Swedes and Norwegians enjoy a traditional food–lutefisk–during the holiday season. It is usually dried or salted cod pickled in lye, rehydrated for several days. Then it is boiled and served with boiled potatoes, mashed green peas, bits of fried bacon and covered in a white sauce flavored with spices. It was more popular among Scandinavian-Americans than in the homeland and is served at Lutheran church halls and fraternal lodges.

The Swedish immigrants had julbord in the form of an elaborate smorgasbord, which was served as the main meal on Christmas. It consisted of hot and cold foods. The first course was pickled herring and cured salmon followed by obligatory julskinka/Christmas ham, liver paté, red beet salad and cheese, the third course was meatballs, sausage, pork ribs, and cabbage. All of this was washed down with a special Christmas wine. The flood of food on Christmas Day was reminiscent of the celebration after a period of fasting, according to pre-Reformation Catholic tradition, from the beginning of Advent until midnight on Christmas Eve.

In the colonial Upper Peninsula the French Canadians introduced and celebrated the earliest religious celebrations which were picked up by later immigrants. A traditional food was the tourtière or pork pie for Christmas and New Year filled with ground pork, finely chopped onions, ground cloves, allspice and some sage. The tradition was for the family to attend Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve and then return home where the réveillon (waking) meal was celebrated. This was a special meal that was costly to many of these people who were common workers and did not usually eat in such abundance. The table was set with candles at both ends and there were cranberries, relishes, foods of all sorts–oysters on the half shell, creamy pea soup, and other items but central to the meal was pork pie. Desserts included mashed potato donuts or réveillon beigne, gumdrop-nut-raisin cake along with pumpkin and other fruit pies. After the grand midnight meal gifts were opened. On February 6, the Epiphany or “the feast of the Three Kings” another celebration took place symbolized by the king cake. It was a special coffee cake baked with a bean inside. The person lucky enough to find the bean was considered king/queen for the day or had to present a cake the following year.

Two traditional sweet treats dominated the Cornish celebration of Christmas. Figgy duff, first mentioned in the fourteenth century, was brought to the UP by Cornish immigrants. It is a precursor of plum pudding. The term comes from Cornish colloquialisms: figgy or raisins and duff or pudding. It is baked and is not as rich nor complex as plum pudding. It is served with clotted cream. Plum pudding was also a Christmas treat with similar ingredients but was boiled for 5-6 hours and served with a brandy sauce.

Polish households served a meal of cabbage and potatoes on meatless Christmas Eve. On Christmas Day family sat around a table with an empty seat for any stranger that might appear at the door. Pirogis (dumplings filled with mushrooms and sauerkraut), kluski (potato dumplings), ham, kielbasa and babka (bread) were served.

Italian immigrants, especially those from southern Italy, celebrated the “Feast of the Seven Fish” on Christmas Eve. Fish had to be served as the eve of Christmas was a day of abstinence from meat. It is unclear why seven fish were part of this meal, unless there was a connection with the seven Catholic sacraments. The fish were served as appetizers, in salads and on to the main course. Baccalà or salt cod fish was the basic fish served in a variety of ways but usually with pasta; there could also be clams and pasta, oysters, deep fried scallops, octopus salad, stuffed calamari, pasta with anchovies and whatever fish that could be purchased.

Italians also had a variety of Christmas sweets depending on the region they came from. Northern Italians, who dominated the mining areas, had panettone, a Milanese lightly sweet fruit studded fruit cake, which is now readily available at Christmas time at Walgreens. The Tuscans centered in Hancock had fruit and nut laden, panforte. The Piedmonese in the Copper Country made nut nougat (-torrone) and torchetti, twisted butter cookies. Pizzella or waffle cookies, usually flavored with anise and baked on an iron form, were popular with all Italians along with biscotti (double-baked cookie) and fried angel wings or bowtie cookies covered in powdered sugar. Imported chestnuts were roasted and eaten in the evening around the table with a glass of red wine. Cinnamon walnuts were a Christmas favorite among Genovese immigrants.

The Croatians and Slovenians in the Copper Country made nut roll at Christmas time. It was called povitica by the former and potica by the latter. It is a sweet pastry made with a yeast raised dough then rolled or stretched out thinly and then spread with ground walnuts, honey or sugar and then rolled up jellyroll style in a log or crescent shape.

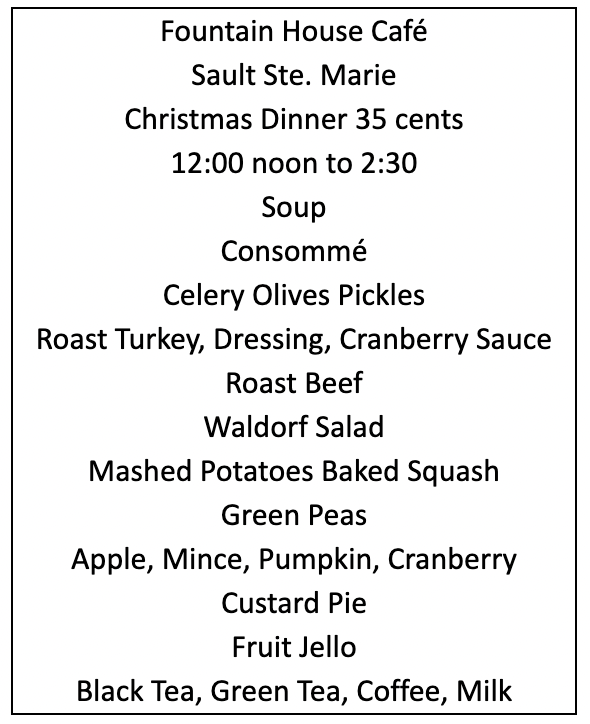

For many non-immigrants the holiday season was a time to enjoy a meal in a café, restaurant or hotel dining room. The following is a typical menu from Christmas 1915:

Up to the present mailing gifts is a major concern and was the same in the past. Newspapers were filled with advice on how to pack and when to ship domestically and internationally. Lines of patrons passed into the streets in front of the post offices whose clerks were nearly overwhelmed.

The UP is blessed to have a town named “Christmas” 4½ miles west of Munising in Alger County. When Julius Thorson bought the land in 1938 it was swamp. He built a factory to make gift articles and with the holiday trade in mind he named the place Christmas. In June 1940 a fire wiped out his factory and thus ended the endeavor, but the name remained. On July 8, 1966 the village received its own post office, with its own post mark and eventually ZIP (49862) due to the efforts of Congressman Raymond Clevenger. On November 2 of that year Clevenger, Deputy Postmaster General and state politicians were on hand to issue the first day cover from the appropriately named town. Today some people drive for miles to send their Christmas cards from this iconic post office.

Thus our trip through the centuries comes to an appropriate conclusion with the Christmas season firmly established in the Upper Peninsula. Some of the traditions remain with us, while others have changed given the times and technology as we look at Christmas 2021.

FOOTNOTES

1The lines given here are but one of many versions of the Guignolée — a song and also a custom brought to Canada by its first French colonists; and a more or less Christianized survival of Druidic times. This name (also appearing as La Ignolée, Guillonée, etc.) is a corruption of the cry, Au gui l’an neuf! “To the mistletoe, this new year!”

Wow, Russ has done again. Teriffic explanation. Though I’ve lived in the U P most of my 79 years, he has revealed things I didn’t know. Thanks Dr.M!

Agreed! I am sending this as an “e-Christmas card” to friends and family with U.P. connections. Absoluely fascinating!

Enjoyed your trip through Christmas in the UP!

Merry Christmas

What a wonderful article,read with intensity

Merry Christmas all!!

Thank you Dr. Magnaghi for sharing the insightful history of Christmas in the UP. I hope that this is shared with family everywhere.

Blessed Christmas and a Happy and Healthy New Year

Born in the u.p. in 1952 and trying to get back ever sense. Love the history lesson and all the different Christmas celibrations and foods of our area. Thanks for the great story and more history of Chistmas, MI.

Thank you! I certainly remember many of the traditions you mentioned being Italian and from Iron Mountain. Our Swedish and French background friends joined in, we shared our traditions with each other.

Just read this aloud as we travel. Beautiful. Just, yesterday during “lumber Jack days” at my grandson’s school they are the French “donuts” mentioned in this writing.

Thank you!

I loved reading this and get a new, richer perspective on my favorite holiday. Thanks.

Interesting read. Some of these traditions are celebrated by my family to this day. It was nice to find out where and when these traditions came from.