Keweenaw National Historical Park and Calumet: What You See is What You Get

Historic preservation is a major force in shaping the American landscape. Each year millions of Americans flock to historical sites to experience places that authentically represent the past.

When the National Trust for Historic Preservation created a heritage tourism program in 1990, it estimated that half of all US tourism was heritage-based. On the Keweenaw Peninsula a number of historic sites tied to a flourishing nineteenth and early-twentieth-century copper industry have been developed as tourist attractions.

The largest attraction is Keweenaw National Historical Park which consists of Calumet and the Quincy Mining District, as well as 21 Keweenaw Heritage sites scattered across the peninsula that are not federally funded.

Calumet’s preserved landscape is illustrative of a corporate mining townscape where the Calumet and Hecla mining company once provided workers’ homes, a school, and library while also donating land for churches.

This article examines some of the unique challenges surrounding the park’s development in Calumet. First, the role of the National Park Service (NPS) in developing and promoting historic sites is outlined.

Beginning in the 1960s, the NPS began awarding National Historic Landmark status to privately owned properties that met a set of national significance criteria. The program was conceived as a cost effective means of preserving historic structures without requiring their acquisition by the Park Service.

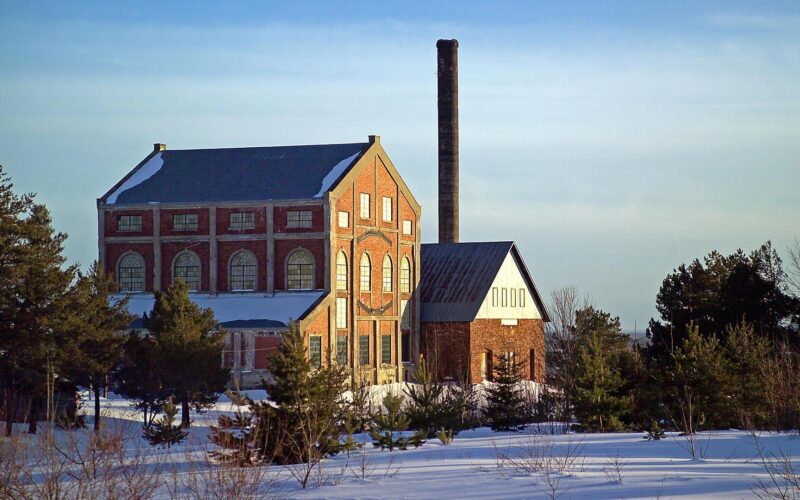

In the 1970s, a National Historic Register Survey was undertaken documenting the role of the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company and the village of Calumet in developing the region’s copper mining industry. The survey provided the foundation for a National Historic Landmark application for downtown Calumet that was subsequently granted in 1989 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Calumet historic district boundary

Three years later, Keweenaw National Historical Park (KNHP) was established with the goal of preserving and interpreting the natural and cultural resources related to copper mining on the Keweenaw Peninsula. The Calumet portion of the park included all of downtown and the immediate surrounding area for a total of 750 acres.

The politics of the time fundamentally shaped KNHP’s creation. When the Park’s development was under consideration local residents were concerned that the federal government would take ownership of their homes. At the same time, federal budget cuts, the difficulty of federal land acquisition, and relatively large local populations meant that the creation of KHNP required that much of the land within the park remain privately-owned.

On a practical level this means that the NPS only owns 135 acres out of the 1,870 acres of the federally-designated land area in Calumet and Quincy and thus has little control over how land is used within the park. Instead, it works with an Advisory Commission made up mostly local residents on park planning, preservation, interpretation, and operational matters.

An early park planning document states: ‘The recognition of America’s copper mining story on the Keweenaw Peninsula is an attempt to protect the experience of the place.’ This means that for a visitor to experience the past, a heritage landscape should look much as it did during a particular historic period with few or no modern intrusions. This so-called architectural design integrity is critical for any heritage landscape.

However, since most land is privately-owned within the park it is often difficult to maintain design integrity. Indeed, soon after the park was created the Mine Street Station retail complex was constructed on mining ruins at the edge of Calumet’s historic district.

Since the land was privately- owned and local zoning imposed few restrictions there was little the Park Service could do to influence the project. The complex with its tall sign is one of the first impressions for a park visitor who travels into the village from the south, and with an abandoned Shopko store, supermarket, offices, hotel, dollar store, fast food restaurant and large parking lot it – this could be anywhere in the USA.

Another example of the loss of architectural integrity concerns one of the most famous landmarks within Calumet’s historic district – the Calumet Theater, located at the corner of 6th and Elm. It was constructed as an opera house in 1900 and is registered as a National Historic Landmark.

Looking at the structure from the west along Elm Street, visitors will notice a large Family Dollar sign in the background. The store is located outside the historic district boundary on 4th street.

Downtown Calumet is a functioning business area with a gas station, retail outlets, several bars, restaurants and other services. A number of these businesses were constructed before the area’s Landmark status and are out of character with the design integrity of particular blocks (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The ‘old’ and the ‘new’ on 6th Street, Calumet

As the region’s population and economy have declined, some buildings have fallen into disrepair, while others have been removed leaving gaps that have been transformed into parking lots. Driving into downtown, on the 100 block of 6th Street, there is an old red sandstone residential structure with a partially destroyed roof (Figure 3), while on the 600 block of Elm Street there is an abandoned commercial sandstone building (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Dilapidated structure on 6th Street, Calumet

Figure 4. Boarded up structure on Elm Street, Calumet

These and other boarded-up structures give the visitor a sense of urban decay, rather than a sense of historical significance. The NPS has a Historic Structure Stabilization fund which is designed to ‘mothball’ historic structures and prevent their further deterioration.

The Agnitz block, built in 1895 and located on the north end of Fifth Street, received emergency repairs under the Stabilization program in 2011. A decade or so later, the building is still awaiting its restoration (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The Agnitz block, north 5th Street, Calumet

Restoring old buildings and maintaining them is an expensive proposition. Over a million dollars, for example, has been spent on restoring and developing the former St. Anne’s Church into the Keweenaw Heritage Center at the corner of 5th and Scott streets (Figure 6), with more than half that sum coming from private sources.

Figure 6. Keweenaw Heritage Center, Calumet

However, in a region with limited financial resources and federal funding for the Park Service largely unchanged since 2010, the ability to fund building restoration projects is limited.

The ever-growing sense of “placelessness” conveyed by urban decay and modern American architecture leaves post-industrial communities like Calumet in an odd position. Parts of its downtown provide visitors with a unique sense of place, an early twentieth-century copper mining community. But the landscape also consists of abandoned and boarded-up buildings, while beyond the historic district are parking lots and shopping complexes from the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

What you see in downtown Calumet is complicated–a storied past and uncertain future.

Historic preservation often means nothing can be changed. Buildings could be repurposed to attract visitors: lodging, restaurants, retail space if they were made available for such to private development since government funds aren’t forthcoming. The lack of an employable workforce also limits the options. There is no real effort to display the historic roots other than a few museums with static displays. They don’t serve as a destination. The Keweenaw is basically a dead-end road to Copper Harbor, a visitor has to be dedicated to travel there and back. More emphasis on recreational opportunities beside snowmobiling in the winter and mountain biking in the summer needs to be developed and promoted. Without a lead person with a vision for the Peninsula, the ravages of time will continue to spread decay.

It’s refreshing to see what could be a opportunity in its infancy, the world’s population is ever growing and and nice place like this could develop into a once again prospering community.