Left Behind Places: The Example of the Upper Peninsula

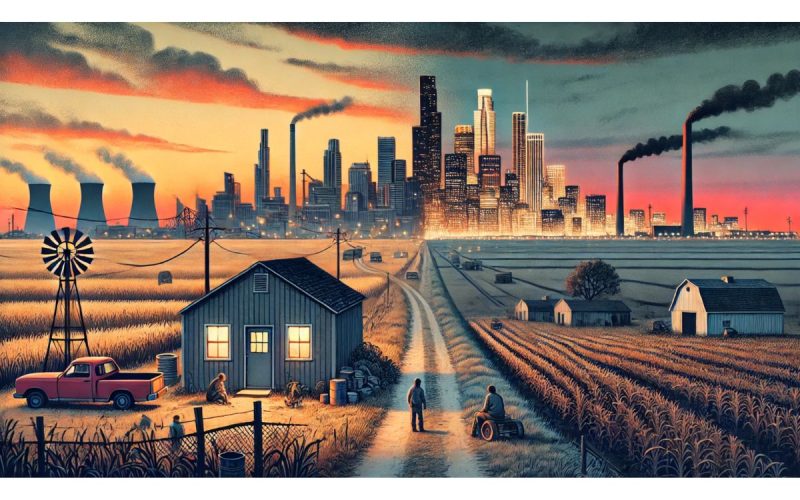

“Left behind places” is a term popularized in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election to explain President Trump’s electoral success in places that had previously supported President Obama. There is no widely accepted definition or means of measurement but the term remains widely used to denote any place, (i.e. a region, or city) that has failed to experience the growth in incomes, jobs and productivity that other “more successful” places have enjoyed.

Left-behind places can be rural, urban, or suburban. A 2024 nationwide study from the Economic Innovation Group, defined “left-behind places” as counties that experienced less than half the national population and median household income growth rates between 2000 and 2016. Using that definition, 972 counties out of 3,144 were classified as left behind, with Illinois, Michigan, and Ohio being the only states where a majority of residents live in such counties. In Michigan, all of the Upper Peninsula’s counties, except for Marquette and Keweenaw, were classified as “left behind.”

Although the term may be new, the problem of uneven economic development is not. In the 1960s, President Johnson’s War on Poverty was initiated by “The People Left Behind,” a report that identified areas where people lacked access to clean water, health care, habitable housing and other modern amenities. Nor is this issue unique to the United States; most advanced economies have “left behind” regions.

This article examines the factors behind the widening gap in economic opportunity within the United States and considers the gap in wages and employment growth between the Upper Peninsula and the rest of the nation.

Being Left Behind

For much of the 20th century, economists theorized that regional differences in wages, unemployment, and business formation would dissipate over time, as business ideas diffused and cost differentials motivated people and firms to relocate to lower-cost regions. This theory was largely supported in the period after 1945.

But beginning in the 1980s, technological and regulatory changes alongside globalization have weakened the forces behind regional convergence. The development of global supply chains has allowed businesses to shift production to cheaper offshore locations, while technological advances mean fewer people are employed in traditional industries. In rural areas, shrinking employment opportunities result in people leaving, which in turn erodes the social fabric of left behind communities.

Researchers have identified increases in so-called “deaths of despair” (suicide, drug and alcohol abuse) among middle-age white people without a college degree in areas with shrinking economic opportunities.

New jobs in the knowledge economy (e.g. health care, computer software) are dependent upon a well-educated workforce. Companies and individuals in these sectors benefit from the effects of agglomeration, whereby the concentration of highly skilled workers attracts new businesses, which in turn attracts more talented workers. The competition for talent means substantial wage hikes and increased productivity. The result of this process is that much of the nation’s economic growth is concentrated in a few large coastal metropolitan areas.

At the same time that technological innovations were benefiting a small number of large metropolitan areas, the deregulation of certain sectors of the economy has worked to the disadvantage of small towns and rural areas. The passage of the Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 removed regulations on interstate branching, and led to a rapid consolidation within banking.

Small community banks lost market share to larger institutions, and while they are not the sole source of capital for local ventures, they have historically served an important role in helping new businesses get started. A decade or so earlier, the airline industry was deregulated with the abolition of the Civil Aeronautics Board. One of the Board’s functions was to ensure the cost of flying to and from small and midsize cities was roughly on par with flights to and from large cities.

With the Board’s abolition, benefits accrued to large domestic and international airport hubs to the detriment of passengers and businesses in smaller markets. A few years later, the adoption of a lax antitrust framework at the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division and the Federal Trade Commission led to a wave of corporate consolidation that, in turn, hurt the ability of small local entrepreneurs to compete.

The combined effect of these processes has been to benefit a select number of coastal metropolitan areas (e.g. New York City, Washington D.C., San Francisco and San Jose) in terms of employment and wage growth, leaving much of the rest of the country behind.

Wage and Employment Growth in the Upper Peninsula

The data for this analysis is provided by the Department of Labor’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages and covers all private sector jobs. In the first quarter of 2020, the US average weekly wage was $1,236; the equivalent figure in 2024 was $1,550. Average weekly wages in U.P. counties are below the national figures for both time periods, and nine counties failed to keep up with the national increase in wages, meaning these places are falling behind (Table 1). Between January 2020 and January 2024, the number of jobs in the U.S. increased by 3.7 percent, in the Upper Peninsula the corresponding figure is 1.0 percent (Table 2).

Conclusions

Over the past four years the U.P. has fallen behind national increases in wages and employment. Its “left behind” status is the product of deregulation and technological changes that are beyond the control of local policy makers. And while there is some evidence of recent population growth in the region, (Marquette County’s population, for example, is estimated to have increased by 1,000 between 2020 and 2023), this increase is unlikely to have much influence on boosting wages and employment compared with national trends.

Given the well-documented widening gap in economic opportunities, it should not be surprising that people who remain in “left behind” places feel marginalized and forgotten. The challenge for policy makers is to craft a more equitable approach to economic development or risk rising inequality and discontent.

It will not be an easy task.

Thank you for this idea. I wonder if there is information about how being identified as living in a “left behind” area affects people’s perception of where they live.

The seasonal economic boost from tourism is oftentimes insufficient to sustain smaller communities. Over-reliance on vape / CBD retail and gambling venues is ineffective. This begs the question: where are the new ideas?

Michael, thank you for your insightful article.

living near munising begs a few questions about affordable housing or rental accommodations.. there is little to none .. on top of the fact that wages paid are insufficient to make housing affordable… many jobs are seasonal which makes for a long winter… a high school graduate has little reason to remain a resident unless they choose to live with mom and dad… the availability of a living wages are few and far between… more industry and light industrial options are needed … possibly a tax incentive to attract business would help … the town is slowly but surely dying 😐

Good piece. The important recognition that deregulation was the key ingredient aiding and abetting this hollowing out of the economies of left behind places, like the U.P. certainly isn’t mentioned often, and we aren’t hearing it from most politicians of either side. The incoming Trump administration and the Congress and the majority on the Supreme Court are interested in more deregulation. One should not foresee good outcomes for left behind places as patterns of monopolization and consolidation rationally flow from deregulation.

Maybe there is something good in what “intellectuals” term “left behind” ?

The poet Paul Simon summed it up neatly: There’s nothing but the dead of night back in my little town.

I know there is a large building outside Marquette or Ishpeming that appears to be for training in the trades. I have a cabin near Amasa, and getting various contractors to remote locations is tough. I’ve been told, on multiple occasions, that contractors are super busy building/renovating cabins and there is a shortage of workers. Seems like there is a market for younger people in the trades to focus on seasonal cabin owners, who, many times have the means, but not the time or expertise to upgrade/maintain their cabins. Have my cabin for 35 yrs, been hearing this for years.

Really great article! It does a great job highlighting how places like the Upper Peninsula are often overlooked when it comes to resources and opportunities. It’s such an important issue, and I hope the recent funding for mental health services in Michigan can help make a difference in these communities. Thanks for bringing attention to this!

While the analysis is thought, the DOL statistics refer to private sector jobs. Given the number of state employees in the U.P. (universities, state police, various agencies), this may be a more accurate tale; I’m not saying that this would not make the U.P. “left behind” but it would certainly not create the seemingly endemic problem denoted solely by these statistics. Admittedly, several counties north of the bridge have struggled economically since the late 1970s and the allure of natural resources providing copious employment and wages for long periods has again subsided…for now. People will always seek to point out that the U.P. is economically disadvantaged and yet, we who choose to live here will find ways to thrive and survive.

This is yet another example where you have, I believe, used “statistics”to try and support your predetermined conclusion. You have overlooked several important facts. First, many live in these “left behind” areas by choice and are very happy including many retirees whose income is not included in your “statistics.” Second, as mentioned above, your “statistics” do not include public sector jobs which are numerous and have much higher weekly wages.Third, you do not recognize the strong feeling of life-long residents to keep things as they are. Surely, you are aware of the push-back of “too many tourists”. Fourth, you don’t mention weather. While some may like the outdoor opportunities in the UP, many do not. and would prefer to locate in areas that offer different opportunities, i.g. college grads locating in Chicago and Atlanta. You offer no evidence to support your conclusions that people feel “marginalized and forgotten” or that there is “rising discontent.” Maybe, just maybe, being “left behind” is not a bad thing. I suggest striving for “equitable” economic development is nothing more than a straw dog.

I found this article really insightful. It highlights how Michigan’s Upper Peninsula has been struggling economically, with most areas—except Marquette and Keweenaw—facing stagnant growth and limited opportunities due to globalization and declining industries. It’s sad to see how these disparities have led to population loss and fewer prospects for the people living there. I agree with the author that policymakers need to step up and address these regional inequalities. Supporting rural areas like the U.P. with fair economic development strategies is crucial to ensure they aren’t left further behind.

“Thank you for shedding light on the unique challenges facing the Upper Peninsula. Your analysis underscores how geographic isolation, shrinking populations, and limited economic diversification continue to impact rural communities like the UP.

Thank you for this wonderful article! The overall analysis is clear, well-supported, and raises important policy implications about addressing enduring regional inequality.