Michigan’s Urban-Rural Divide

Recent structural economic changes in the US economy have led some observers to argue that the country is evolving into two separate entities: one rural, the other urban.

Rural areas, they suggest, are falling behind large metropolitan areas in terms of job and income growth, with some researchers suggesting that this widening gap is leading some rural residents to resent their urban counterparts (see Katherine Kramer’s study of Wisconsin in The Politics of Resentment).

Rural areas’ traditional employers such as forestry, mining and farming continue to shed labor as a result of gains in worker productivity and competitive pressures. Since 1982, the number of Michigan farms has declined by over 10,000, while the number of persons employed in mining has fallen steadily for decades.

In Marquette County, mining employment has been cut in half over the past thirty years due to the Empire mine closure and productivity gains. In many instances, lower-paying service sector jobs end up replacing these and other jobs. In turn, income growth falters and people move away to find employment elsewhere.

Upon closer examination, however, the situation might not be so clear cut. This article explores the degree to which there is a clear rural-urban split in the state by comparing the economic and demographic performance of the UP’s 15 counties between 1989 and 2019 with a sample of metropolitan counties from ‘below the bridge.’ The data were compiled from Research Division sources at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

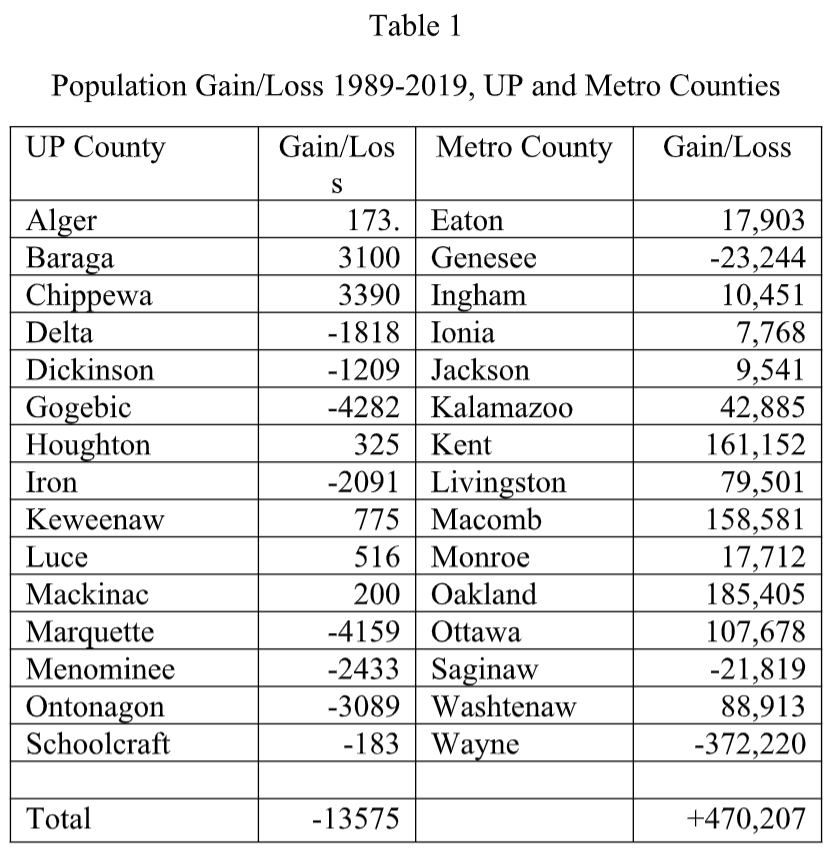

Population Change: Over half of the UP’s counties lost population between 1989 and 2019 (Table 1), as a result of in-migration to the region and the birth rate failing to offset a rise in the number of deaths from an increasingly-aged population.

The net effect is a population loss of about 13,500 persons, with counties in the western half of the region having the largest losses. In contrast, metro counties experienced an overall increase of over 470,000 persons, with the largest gains associated with counties in the Detroit (Oakland and Macomb) and Grand Rapids (Kent and Ottawa) metro areas.

Although the UP lost population, three metro counties also experienced population losses (Saginaw, Genesee and Wayne) due to the faltering fortunes of the auto-dependent cities of Flint and Detroit. In short, the evidence of a widening urban-rural demographic divide is mixed, with both rural and urban counties experiencing population growth and declines.

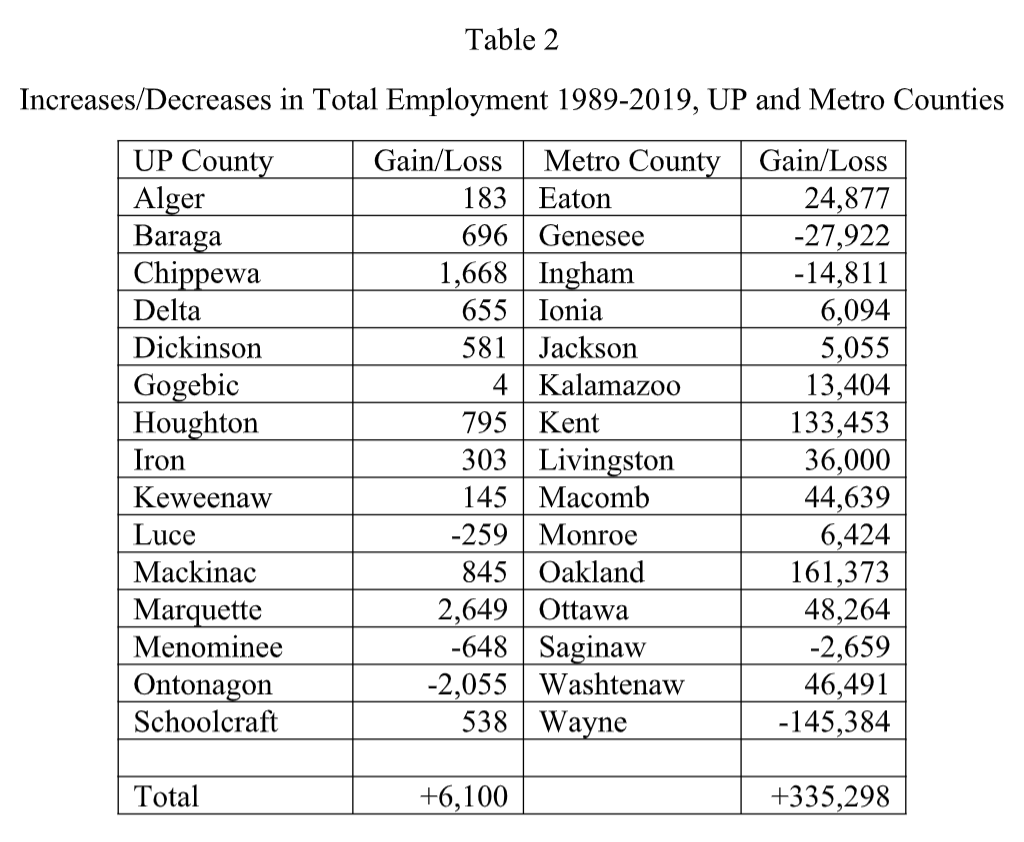

Employment: Despite the UP’s population decline, the total number of persons employed in the region increased by 6,100 persons, or 6 percent (Table 2), with Marquette and Chippewa experiencing the largest gains. Ontonagon had the largest employment drop due to the 1995 White Pine copper mine closure.

Below the bridge, several metropolitan counties that lost population also experienced employment declines; however, overall employment for metropolitan counties increased by 11 percent, almost double the UP’s figure, with the largest percentage gains associated with Eaton (Lansing metro area), Livingston (Detroit) and Ottawa (Grand Rapids).

In sum, the evidence of a widening employment gap between urban and rural Michigan is once again mixed, with metro counties as a whole outperforming the UP in job creation. Yet, metro areas are not immune to job losses, most notably in Wayne and Genesee Counties.

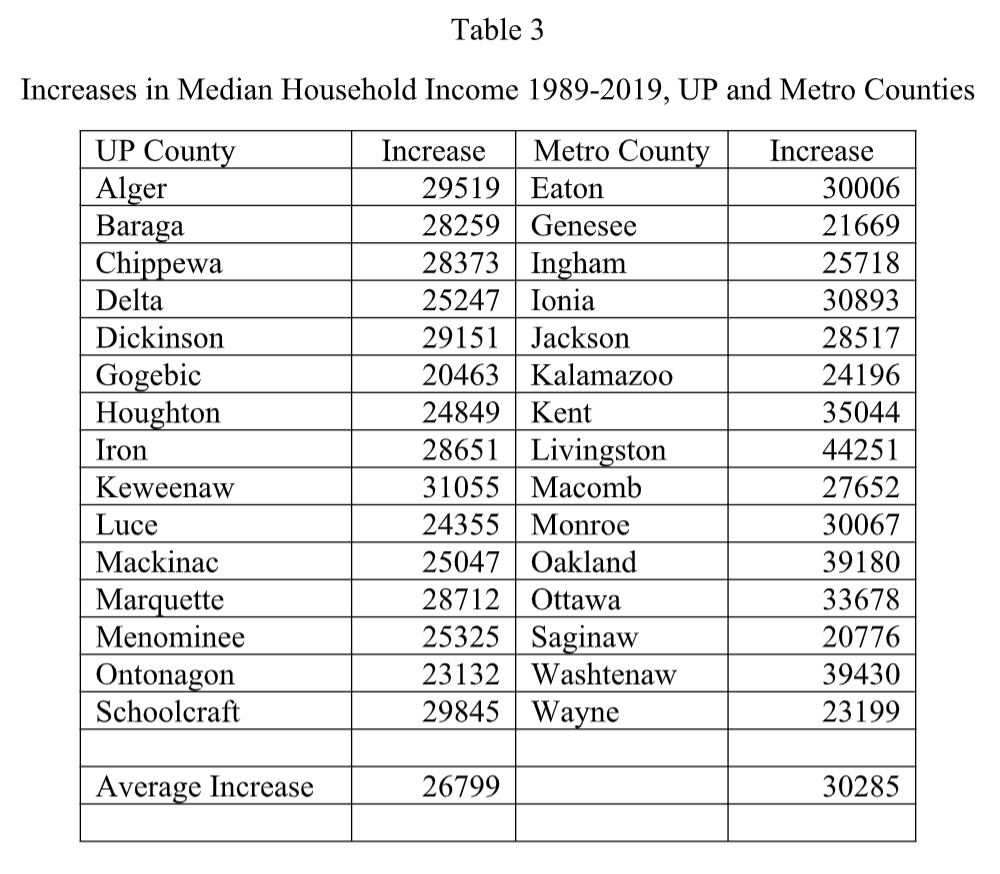

Median Household Income: Michigan’s median household income in 1989 was $30,755, thirty years later, the corresponding figure was $64,119, a gain of $33,364. No UP county matched the state’s increase (Table 3). Indeed, the average increase in median income was $26,799, compared with the metro average of $30,285.

On the surface, this difference is suggestive of a widening rural/urban income gap, however, an analysis of individual counties reveals a more complicated pattern, with some rural counties exceeding the income gains of their metro area counterparts and vice-versa. The evidence of a widening income gap between urban and rural areas is once again mixed.

Poverty: In 1989, the average poverty rate for the 15 UP counties was 13.8, the equivalent figure for metro counties was lower at 9.7. By 2019, the UP’s rate had inched up to 14 percent, while the average rate for metropolitan counties had increased to 12.1 percent. These data indicate that the gap between the UP and metro county poverty rates narrowed due to an increase in metro county poverty, which is contrary to the proposed urban-rural split.

These four analyses provide conflicting evidence of a rural-urban economic split. Over the past thirty years Upper Peninsula counties, compared with their metro counterparts, have experienced population decline, slower job growth, higher poverty and smaller gains in median household incomes.

But some metropolitan counties, most notably Wayne, Genesee and Saginaw, have experienced even more significant job and population losses, as well as increases in poverty, as they continue to experience the long-term effects of deindustrialization. At the same time, there are metro counties that provide evidence of a widening gap in economic conditions between rural and urban counties.

Livingston County, located between Detroit and Lansing, is illustrative: between 1989 and 2019 population increased by 70 percent, total employment more than doubled, median household income went from $43,576 to $87,827, and its poverty rate was largely unchanged at 4 percent. These accomplishments are in marked contrast to both the UP and less fortunate downstate counties.

The distinction between urban and rural is insufficient to contextualize a complex economic reality. Uneven development, where some regions are favored over others in terms of attracting investment and people, is a feature of modern economies. In Michigan, some metro counties are dealing with divestment, while others enjoy ‘boom times.’

A similar phenomenon is evident in the UP, where some counties are experiencing long-term economic decline and others modest growth. Indeed, it might surprise some UP residents to learn that they share some economic similarities with their downstate counterparts.

Thanks for this analysis. Good timing as I consider the economic and political future of my state.

Very interesting data….personal observation from Livingston County in the 80s and 90s. Livingston, particularly Brighton, was the fastest growing county in the state because the numbers were relatively small and increases yielded lage %age increases. None the less, if you dive deeper into the county data you likely find that small communities near major metro areas grew significantly. My belief was people were looking for the social and loer housing offerings of small communities while enjoying the employment opportunities in urban areas.

Your data suggests this trend has reversed, not sure it has. Basic challenge is analysis with numbers rather than percentages often yields contrasting results.

https://www.theatlantic.com/sexes/archive/2013/06/the-particular-struggles-of-rural-women/276803/

https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-counties/mi/alger-county-population

Read the Atlantic article. Look at the 2023 population pyramid for Alger County. The male / female imbalance between ages 20 to 50 is the canary in the coal mine. Alger is just one example. Women are leaving as soon as they graduate from high school and not coming back. The UP, outside of a few counties, is unattractive for women who want a higher education, careers and good marriage prospects. When you lose the base for family formation, you lose the future. Stop blaming those people in the cities and starting facing the facts.