Childcare: An Overview of Costs and Solutions

Childcare is one of the most pressing issues to the modern working family.

With costs as high as the price of a mortgage, it is an expensive necessity for working families. Without it, households must rely on a spouse or a relative for the difficult and time consuming task of raising a child.

This can lower workforce participation, especially that of women, and increase use of social programs such as FAP (Food Assistance Program) or in some cases even push people onto cash subsidies from the government. Childcare can be an inconvenience when there are two adults in the house, but it can be devastating when there is just one.

Any form of childcare can be expensive, but licensed childcare is even more so–sometimes even prohibitively expensive. The annual cost of childcare for a toddler and infant in 52 Michigan counties is over 30% of the median household income, or $17,563 in 2016.

This is more than what a typical family pays for a mortgage. With the costs of childcare being so high, it essentially becomes a tax and a barrier to working. Worse yet, this is a wide-ranging issue–because the cost of care is so great, it can affect even those earning well above the median wage.

At the bottom of the spectrum, those who are above the poverty line but below the ALICE1 line are almost devastated. This is due to Michigan’s bar for assistance, which is 130% of the federal poverty line, or $32,630 for a family of four. For reference, one person working full time at $16.50 an hour would make more than this, and at typical childcare costs they would be spending more than half their income on childcare.

As previously mentioned, there is informal childcare, such as babysitters, and formal childcare, which consists of several different types of childcare facilities. The smallest being the family care centers. These consist of 1-6 children, not including those related to the caregiver by blood, marriage, or adoption.

Family care centers tend to be the most informal, and may be set up by a family member (hence the name). These also tend to be more flexible in their hours, and the most likely to offer after-hour care. Group homes watch after 7-12 children, they also tend to be slightly more formal than the family homes due to their larger size.

Both group homes and family homes provide care to the children more than 4 weeks a year. Childcare centers tend to be the largest, with the only requirement for their nomenclature being that they must care for one or more preschool-age children for less than 24 hours a day. These tend to be the most regulated and have additional star ratings that they can apply for, with 5 stars being the highest and 1 being the lowest.

The highest expense in childcare is the cost of the labor of the caregivers. In part, this is because many people are required to run a center correctly and in line with federal and state regulations. When considering children younger than 12 months, one adult is required for every 3-4 kids, with groups no larger than 6-8.

For children ages 1-2, 3-6 kids are required for every adult, with groups no larger than 6-12. Children ages 2-3 should not be in groups larger than 8-12, and should have a child-to-worker ratio of 1:4-6. Kids ages 3-5 should not be cared for by more than six adults to one child, with no more than twice that in a classroom.

These guidelines are consistent with the ‘Iron Triangle’ of childcare: kids should have a small group size, low staff-child ratios, and high teacher qualifications, including such things as an associate college degree, or other training certificates. These are all things that raise the cost of labor and make childcare expensive.

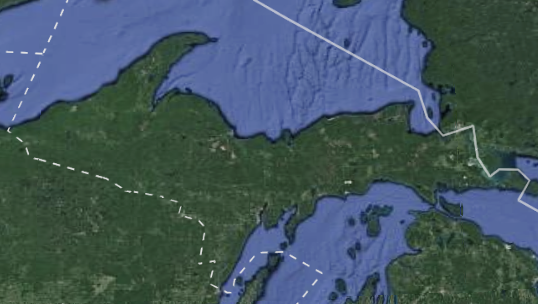

High costs, however, are not the only problem associated with childcare. In many rural areas (and dense poor urban areas, though to a lesser degree), there is the issue of childcare deserts. A childcare desert is an area where there is either no licensed childcare available, or three times as many people looking for childcare as there are open spots.

Unfortunately, due to its rural nature, this describes much of the interior of the UP. The issue is not a lack of availability, it is an absence of licensed childcare centers. There are exceptions: Marquette, Sault Ste. Marie, Munising, and a few other areas, but outside of their micropolitan areas there are but a few pockets of care centers.

The low number of children in these counties probably in part causes this, but this still constitutes a significant issue for those with children.

Added to these high costs and lack of centers, there are also issues with times available for care. As most centers, group homes, and family homes base themselves upon normal working hours, it can lead to issues when it comes to taking care of children during the evening and night.

This can even lead families to forgoing childcare–this comes at a blow to the children, as time lost here has lasting impacts.

Again, the most-affected tend to be the most vulnerable, such as poor children and kids of single parents. As due to their working nature, they may be able to spend substantial amounts of time in the evening with their children.

The issues stated here can contribute to something called the poverty trap. This is where people need capital (whether it be monetary or human) to break the cycle of poverty, yet have significant difficulty coming up with the capital because the obstacles they are facing can only be overcome with some amount of capital.2

In physics, an object in motion tends to stay in motion, and this most certainly seems to be true of poverty and its devastating cycle, as it is easier to create wealth with more wealth and easier to lose it with less—and childcare seems to play an absolute part in this.

Good childcare tends to have a high total cost, in large part because of the Iron Triangle of structural quality. This iron triangle includes three main items, which are low group size, small staff to child ratio, and high teacher qualifications.

Even at an average wage of about $9.50 an hour these costs of staffing3 are the highest when it comes to the aggregate operating costs of a childcare center.4

Two things that tend to support the iron triangle are staff wages and a low teacher turnover. Low turnover is important as young children do better with stable strong relationships–something low turnovers provide.

The last piece of support is one the most important as the wages paid in childcare are so low, it can cost more to care for children than you would make as a child care worker. This has led many childcare workers to terminate employment, and leave the workforce after childbirth.

Aside from being essential to many parents, quality childcare can tremendously help children out later in life (this includes having a stay-at-home parent as well). Studies have shown that good childcare correlates with better overall education.

Though the impact on grades can be fleeting, there are long-term benefits–such as increased high school graduation rates as well as higher rates of college attendance and graduation. As many studies have shown, those who have received only a high school diploma earn just 60% that those with a college degree do.

Even with today’s high college prices, those who graduate from college earn a 15% return on their investment, showing childcare at an early age can lead to later success in life.

Quality is an important factor for outcomes of care, and there are varying levels of it. Childcare centers tend to provide the most regulated and highest quality care, and quality of care is a statistically-significant factor in outcomes, yet it is not exceedingly important for centers to be of the absolute highest quality.

This means that having an adequate level of care compared to poor care provides a much greater result than the jump from fair to excellent care, as the largest contributors to this growth are those coming from economically-disadvantaged backgrounds.

The reason for this is most likely that the quality of care provided at home seems to create a bigger impact than while at an external facility5, and poor children’s parents may not have enough time to spend in the evenings due to circumstances such as working a second job.

The diminishing marginal returns produced from higher quality childcare highlight the idea that safe care, with low staff ratios and enthusiastic staff is the most beneficial.

The solutions people propose to lessen the individual cost of child care seem to fall into two different categories, either by dispersing who pays, or by cutting regulation.

Some examples of the first include using state funds to help increase the maximum amount people can earn while still receiving support and subsidizing child care in general—either through reimbursement or tax deductions for childcare.

When it comes to cutting regulation, many people focus on the ratios required by the state for the children-to-caregivers ratio in care facilities. Though it may be true that there would be a decrease in costs associated with lowering the adult-to-child ratios, it seems they are as low as they should be.

The individual attention given to kids is very helpful in creating the positive impacts childcare gives to kids. One of the important markers of quality in childcare is low group size, and although there might be a slight decrease in price, is it really worth the negative effect that can come with it?

Due to the lower rates of childbirth in the United States, taking advantage of the dispersed effect by utilizing taxes or company child care seems to be the best route. One proposed solution for easing some of the burdens people in the working class face from excessive childcare costs would be to raise the upper limit of who is eligible to receive childcare subsidies; this would raise it from the 130% of poverty line it currently is, which is among the bottom five of all states.

The first three years of life are the most crucial to the cognitive development of a child and an increase in subsidies here might positively alter the course of a kids’ lives, and would generate good returns on investment.

Studies have found that high-quality early childhood development programs have a $4-$9 return on investment for every $1 invested. This would make it the highest-impact investment in human capital through the course of someone’s life–much higher than the 15% for college.

Another option to consider would be companies providing care to employees with onsite childcare. Onsite childcare is almost a luxury these days, with four percent of companies providing free onsite childcare, and four percent offering subsided onsite childcare.

This makes childcare a lucrative benefit for the employer to provide. Larger companies are typically the ones that do this, as it costs a considerable amount and demands a premium for space.

Another more common way care is offered is by paying a childcare subsidy to workers. For both solutions, there are tax benefits that can make this affordable to companies, and this type of compensation can create a higher retention rate and more satisfaction among employees.

Retention of childcare workers also improved through subsidies. Providing a way to increase the efficacy of care could be provisions of subsidies to childcare workers who have a child. There are high rates of caregivers leaving their position as a caregiver, after having a child due to low pay, and high care costs.

This could alleviate some of the turnover these positions are endemic with and provide more stability for the children in the centers.

FOOTNOTES

1ALICE stands for Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed. ALICE households are those with income above the Federal Poverty Level but below the basic cost of living.

2Capital is defined as that part of the wealth of an economy which is utilized for further production of wealth. It includes all forms of reproducible wealth utilized directly or indirectly in the production of a large volume of output. https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/economic-growth/what-is-the-role-of-capital-in-economic-development/4441

3Which are directly impacted by the first two pillars due to labor market pressures.

4The third pillar is directly at odds with the first and second with fixed prices, as when you raise the human capital required for a job, the wage of the job has to increase or it will price a firm out of the market.

5Although this does not mean children fare better in the home, as they tend to statistically do equally well in and out of the home.