Recent Population Changes in the U.P. Amidst the Pandemic

The population dynamics of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula are well documented. Its population, like most rural regions in the United States, is in decline. A falling birth rate, lack of in-migration, and drops in employment in forestry and mining are behind this decline.

With fewer locally available jobs, people leave the region to look for work. In the past, this outmigration was offset by high birth rates, but this is no longer the case; birth rates are falling while an aging population drives up the number of deaths. The net effect of these processes is population decline.

This article examines recently-available data from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services on births and deaths, along with IRS Migration data to provide an update on the most recent population changes in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

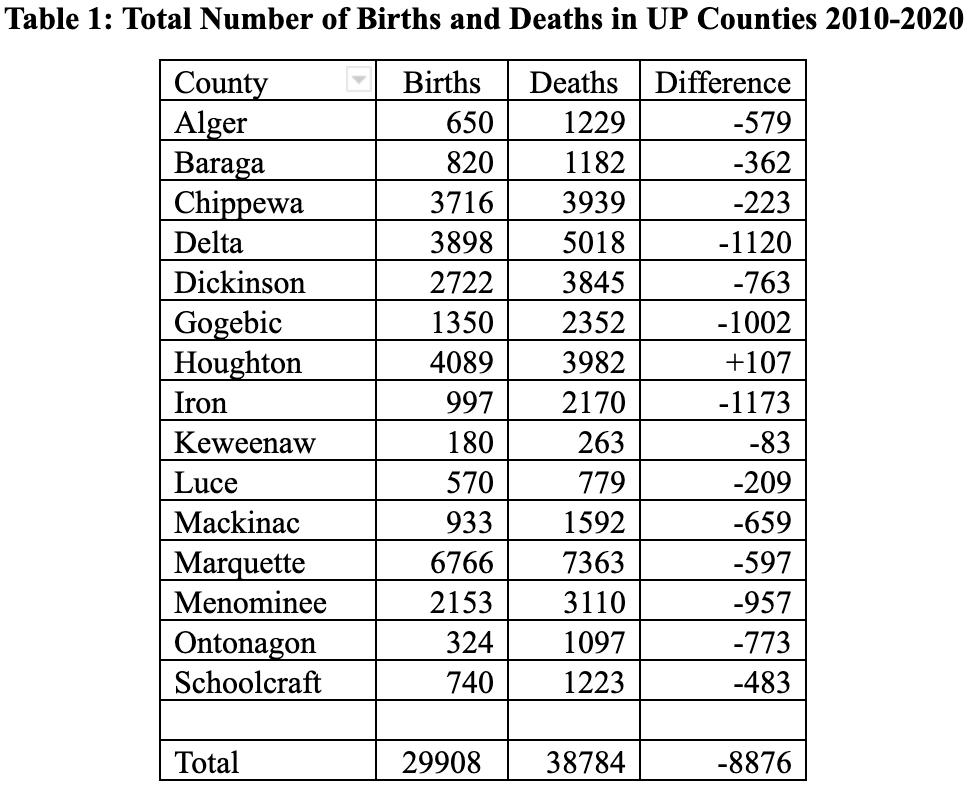

In 2020, the number of births in the U.P. totaled 2,489, down 308 from a decade earlier. (Table 1). Among its 15 counties, Marquette County experienced the biggest drop from 641 births in 2010, to 556 in 2020. The 2010-20 period saw a total of 29,908 births and 38,784 deaths for an overall population deficit of 8,876.

The counties with the largest gap between births and deaths were Iron, Delta, and Gogebic. Only Houghton County had more births than deaths, and not surprisingly, it was the only U.P. county to gain population between 2010 and 2020 according to the Census Bureau.

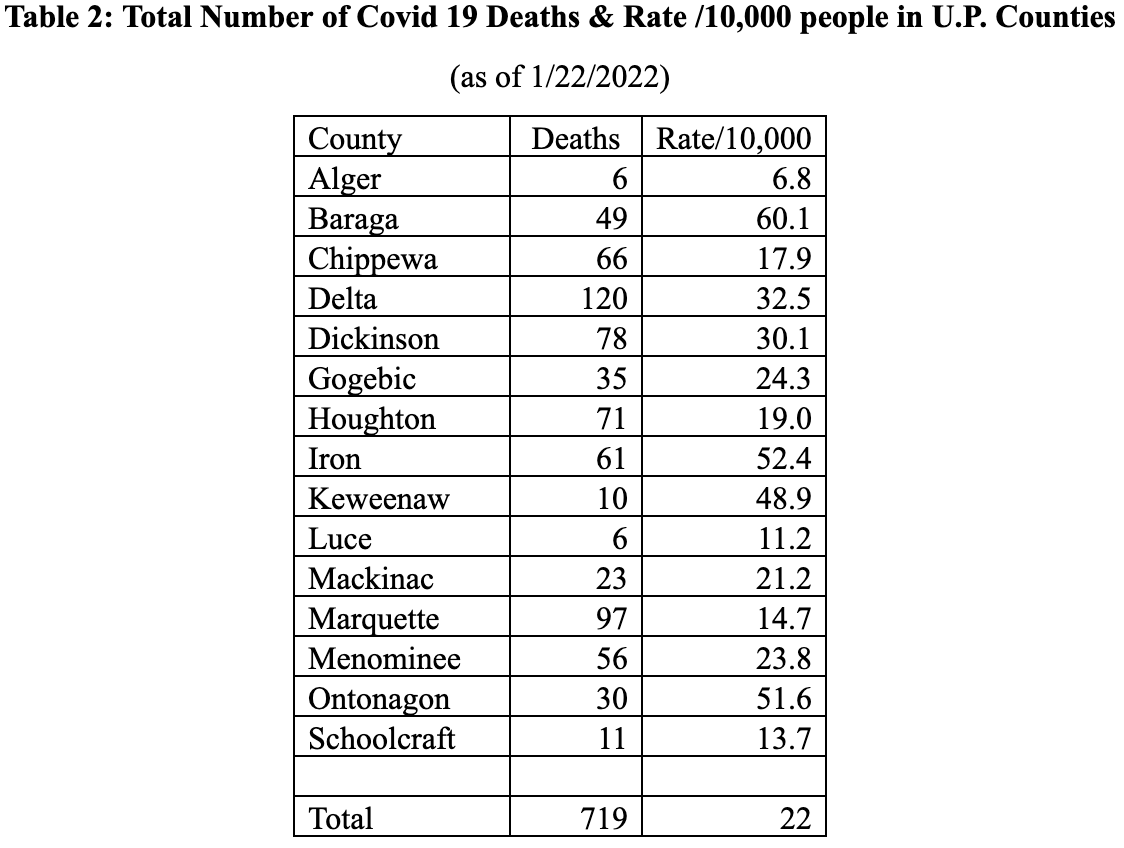

Between 2015 and 2019, the U.P. averaged about 3,600 deaths a year, then Covid-19 hit in 2020, and the number of deaths increased to 4,061. The first reported Covid case in Michigan occurred on March 10, 2020. Since then there have been approximately 29,000 confirmed deaths from Covid in the state (as of January 22, 2022).

Of these, 719 occurred in the Upper Peninsula (Table 2). Delta County has had the most deaths, followed by Marquette and Dickinson Counties. After controlling for the population size and expressing the number of deaths as a rate per 10,000 people–Baraga, Iron, Ontonagon, and Keweenaw counties have the highest Covid mortality rates in the U.P.

The reasons for the variation in mortality rates between counties are beyond the purview of this article. But it is worth noting that a statistically significant relationship was found at the state level between county Covid mortality ranks and their ranking on a health outcomes measure compiled by the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.

The indicator, Years of Potential Life Lost, is a widely used measure of the rate and distribution of premature mortality and is based on 2017-2019 data. It is used by public health officials to identify deaths that could have been “prevented.”

In this instance, the data indicate that counties with the highest Covid mortality rates tend to have the highest rates of premature death in the state. Ontonagon, Baraga, and Iron counties, for example, are ranked in the lowest quartile (lowest 25%) of “healthy” counties in Michigan based on Years of Potential Life Lost, and have some of the highest Covid mortality rates in the state.

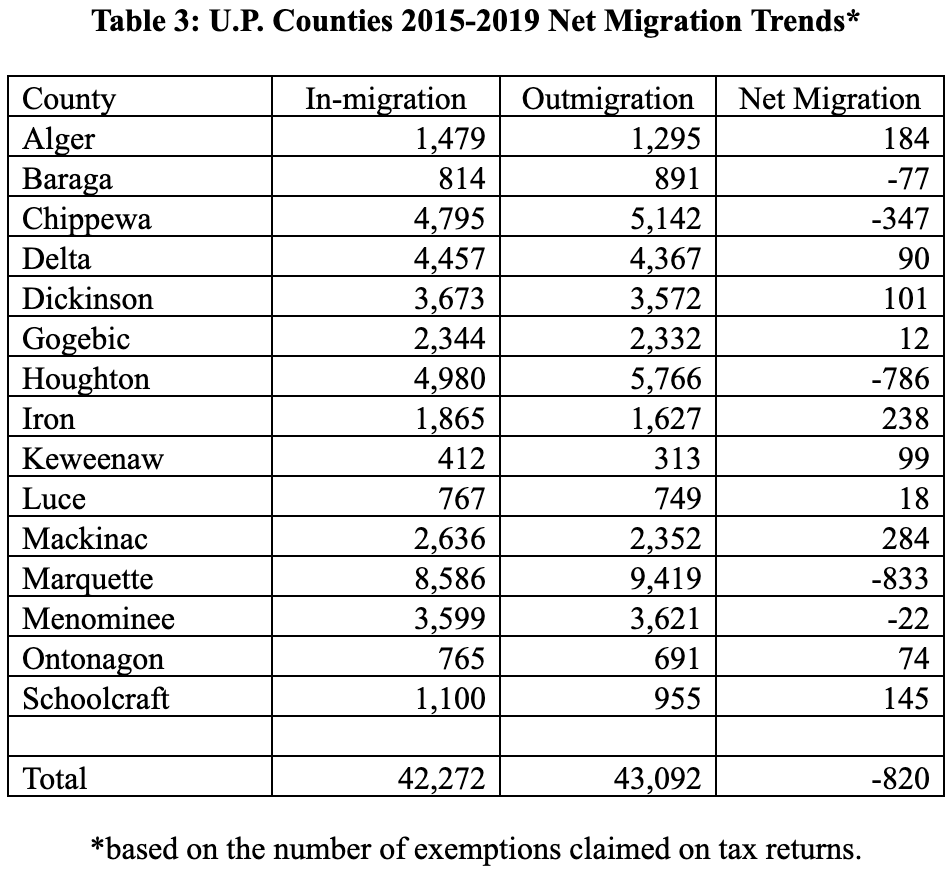

The importance of migration to maintaining the region’s population is illustrated by IRS data on county in-migration and outmigration. These data are based on address changes on individual income tax returns and they do not measure temporary migration such as a person who has a permanent residence in Milwaukee but spends time at their summer home in the U.P.

Despite the fact that not all people file tax returns, the data clearly indicate (Table 3) that over the 2015-16 to 2018-19 period, outmigration exceeded in-migration for the region which saw a total loss of about 820 persons. Marquette, Houghton and Chippewa Counties have the biggest losses, which is, in part, related to their roles as regional service centers hosting universities and hospitals that maintain constant flows of professionals and students.

Positive net migration values (the difference between in- and out-migration) are critical for the region since they help offset population decline. Iron and Mackinac County’s overall population decline, for example, would be much greater were it not for in-migration.

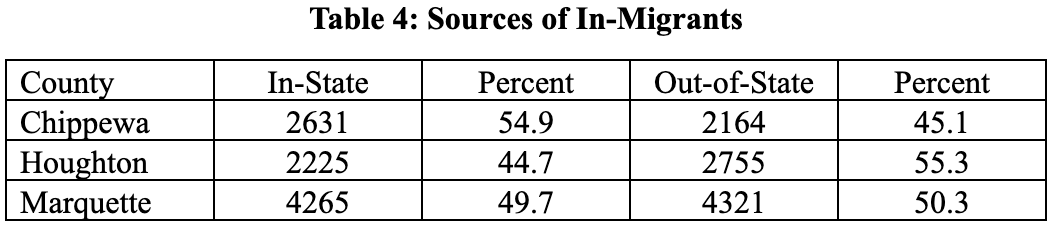

In terms of the origins of migrants, more than half of Chippewa’s in-migrants come from within Michigan, and about half of Marquette’s in-migrants also come from within the state; Houghton is the exception with 55 percent of its migrants being from out-of-state (Table 4). The largest single source of in-migrants to Chippewa County is Mackinac County to its south. Alger County serves that function for Marquette, while Marquette County is the largest supplier of in-migrants to Houghton.

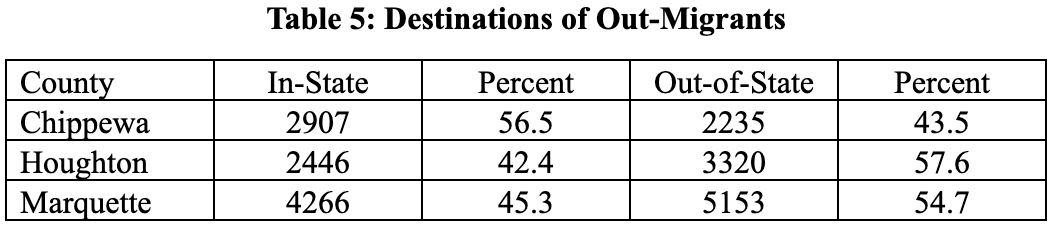

The majority of out-migrants from Chippewa County stay within the state, while the reverse is true for Houghton and Marquette. Employment opportunities appear to be a factor in explaining the destinations for out-migrants. Kent (Grand Rapids) and Oakland (suburban Detroit) counties are major destinations outside the UP for persons leaving Chippewa County. Brown County, WI (Green Bay) and Cook County IL (Chicago) serve the same function for persons leaving Marquette County as does Oakland County for Houghton County.

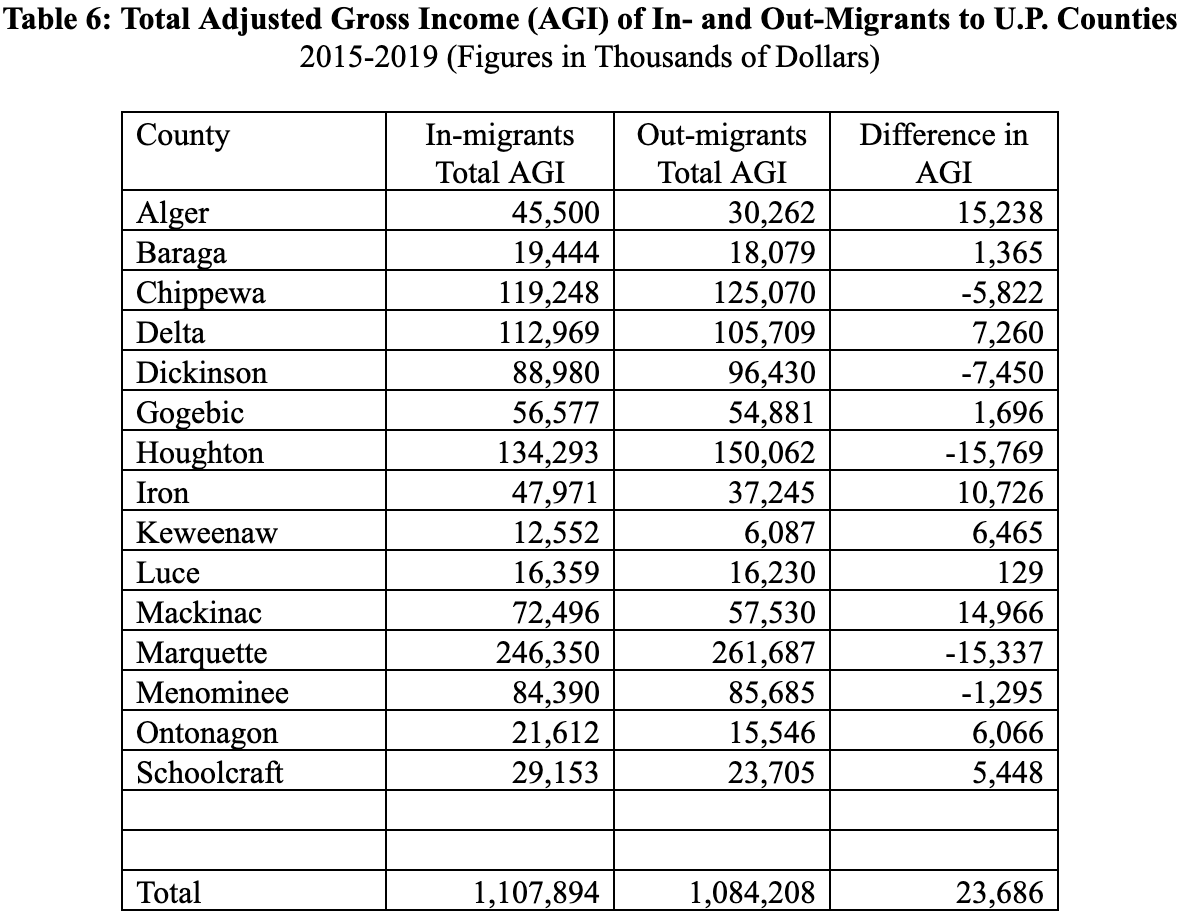

The IRS data aggregates the adjusted gross incomes of in and out-migrants so it’s possible to determine their economic impact. Not surprisingly, with Marquette and Houghton County experiencing a net loss of migrants they also have the biggest “losses” in adjusted gross income between in and out migrants (Table 6).

This figure amounted to a total loss of about $15 million in local purchasing power for each county. Conversely, the total adjusted gross income of migrants to Alger, Mackinac and Iron Counties is significantly higher than their out-migrants. Given their overall population decline, this “extra” income is important for local economies.

The U.P.’s population is a constant state of flux. A falling birth rate means that counties are increasingly dependent upon in-migrants to maintain their population base and local economy. At the same time, deaths from Covid 19 are contributing to the region’s overall population decline.

Indeed, between when the research for this article began using mortality data from January 21, 2022 and writing the conclusion on February 11, an additional 47 people have died from Covid in the U.P. The full impact of the pandemic on the region’s population is a story that is still to be written.