Hidden Homelessness in the Upper Peninsula

Hidden homelessness is a scary reality–it can affect friends, family, and others in the community.

Some people may call it “couch surfing,” but in reality, the connotations are deeper than that. This particular type of homelessness involves people staying in a house or another domicile, such as a hotel, that is not their own for an extended period of time.

This could mean taking over an extra bedroom in a friend’s house you might be paying for, or moving from hotel to hotel with no long-term place of residence. The reasons why someone may need to do this are unique. However, oftentimes a person who is in this situation has already been living on the edge for some time.

All it takes is one event to push you from the edge to the chasm below.

In many ways, hidden homelessness may differ from chronic homelessness.1 An individual who is part of the growing hidden homeless population in the United States may have a job, kids, or may even be a child or teenager themselves.

But due to some life-altering event they may find themselves unable to keep up with rent or a mortgage, with no a safety net to rely on. This can push an individual from keeping up, to falling behind, to being removed from their home.

These significant struggles may cause a person to have to stay at a hotel or to double up (having to live with another person or family for some extended period of time). Although this may sound a million miles away from living on the street, this lack of stability–and quite possibly security–can leave long-lasting effects on children.

This is due to the lack of basic family cohesion, and consistent shelter that comes with inconsistent housing as well as the fact that some of these living situations can be extremely hostile to children.

When people are put into situations where they must subsist on the goodwill of others, it can increase the risk of being subject to predation by those in a position of power over them.

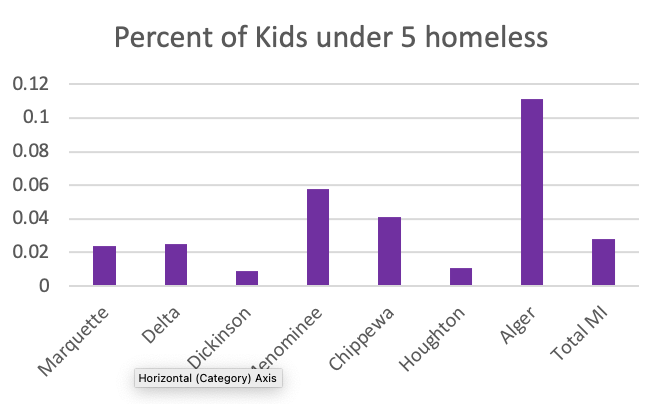

Throughout the Upper Peninsula there can be large discrepancies in the rates of homelessness. These discrepancies are particularly pronounced when referring to the number of young children that may be homeless at any time.2

The variation in the UP ranges from .9% of children in Dickinson County to 11.1% in Alger County. This 10.2% spread among counties represents the fact that there are many people already living close to or below the poverty line.

Yet, this spread may not show the true depths of poverty in the UP, as it does not show those close to but not yet homeless.

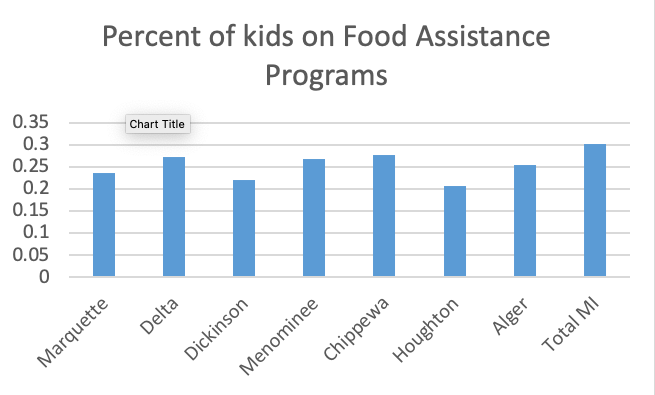

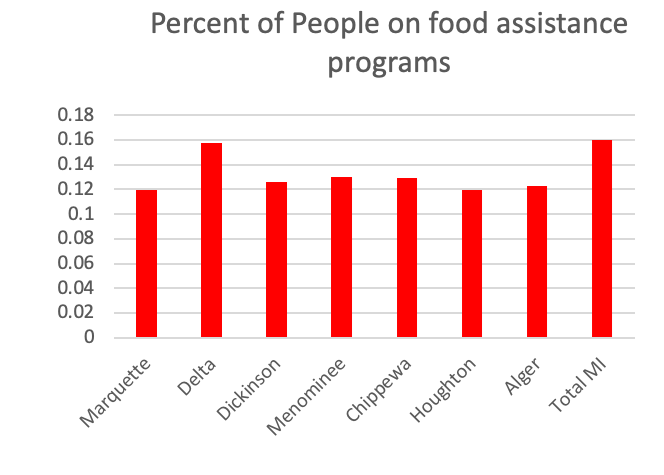

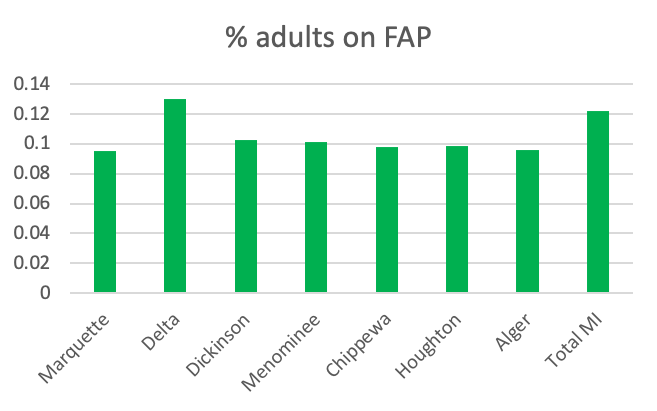

Outside of the official poverty line, there are indicators of how many may be living in this gray area above the official poverty line yet below being able to live securely from paycheck to paycheck. Two of these indicators are the rates of individuals relying on Food Assistance Programs in Michigan and the ALICE3 metrics. These can paint a fuller picture of the state of families and people in the Upper Peninsula.

ALICE is a metric that measures the number of people in a county who live above the poverty line yet below the bare amount needed to live in a typical house or apartment without having to make significant sacrifices.

This is a very precarious situation for people to be in. They may be living from paycheck to paycheck with the knowledge that one missed week of work might push them past the point of being able to eat enough food or pay rent on time.

This ALICE standard looks at the amount that is required in each county to maintain a typical life with absolutely no frills. The main aspects of this standard for a single person are housing, transportation, food, health care, and technology (which has grown ever-more important in this increasingly-digital age).

For example, the minimum amount necessary to live without fear of imminent catastrophe in Marquette Michigan is $9.97 an hour, 40 hours a week, or about $20,000 a year. As someone who lives in Marquette, I find this figure to be accurate, as with less I would imagine it very hard to survive without assistance.

The ALICE numbers also show how devastating a real shock like the coronavirus pandemic can be. These statistics, in particular the amount of people at or below the ALICE level, have not yet been updated for the 2020 fiscal year. Though, without much imagination, I could believe that these numbers will show that these conditions will have become all the more dire.

The numbers show that although many people in the UP may be living above the federal poverty line, things are still very difficult. This means that when confronted with a loss in employment, or hours worked, many people who are currently close to requiring assistance may be pushed into needed assistance, and those needing assistance may be pushed into something worse.

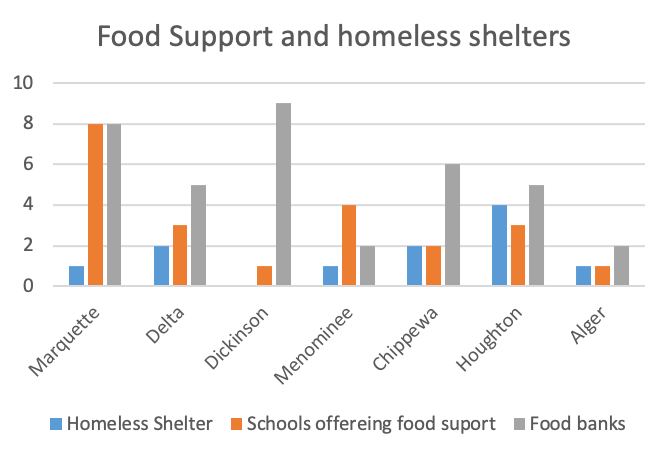

Out of the seven counties that I looked at (Marquette, Delta, Dickinson, Menominee, Chippewa, Houghton, and Alger), there seemed to be some indication that people are struggling. Some of the worrying statistics that I found showed high poverty and ALICE rates, as well as some counties having extremely high rates of homelessness for children under the age of four.

In reference to the ALICE rates, the counties that I looked at were an average of 6.4% higher than Michigan’s average of 29%. These counties also had a poverty rate of 12.24% higher than the average of Michigan (14.14%).

The most alarming statistic I found indicated that there were some extremely high rates of homelessness for kids under four years old, the highest being Alger county where the rates of young homelessness are almost four times the state average.

This 11.1% homelessness rate seems to indicate that there are some significant underlying issues in the community. The rate in Alger is the highest; however, there are also some issues with this in Menominee, where the rate is over two times the state average, as well as Chippewa (one and a half times the state average).

These are all significantly above the state average and are issues that need to be addressed, as early homelessness can be extremely detrimental to children.

The number of people who are homeless in rural areas is almost twice that of urban areas. Along with this there are also not nearly as many assistance programs in the UP, and those that do exist tend to be focused in the bigger cities in particular counties.

Most of the counties that I looked at found themselves with one or fewer homeless shelters, and ten or fewer food banks or other institutions where people could get free food on a need-based level. Also, as I went to call some homeless shelters, many did not have working phone numbers on their websites, and some that I was able to get in contact with would not speak with me.

The problem of homelessness, or poverty is not just in a far-off city such as Detroit or Milwaukee but in fact could be our friends, neighbors, or family. This situation that some find themselves in is significant and serious; there may not be actual federal or state resources to help them.

The only thing that there is to do is to be kind, and understand that the struggles people face may be deeper than they appear to be on the surface level.

Footnotes

1An unaccompanied individual, who has been continuously homeless for longer than a year, with a minimum of 4 episodes in the past year. This individual lives on the street or some other place that is unintended for human residence.

2Children under the age of four. Many children in this position are hard to track due to their age, and the fact that homeless children are 80% less likely to be in any form of childcare or preschool.

3Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed

https://www.bridgemi.com/children-families/rural-children-more-twice-likely-be-homeless-michigan

https://joinpdx.org/the-many-forms-of-homelessness/

https://poverty.umich.edu/research-publications/policy-briefs/homelessness-michigan-schools/