Hotel Tax in the Upper Peninsula

Have you ever seen a hotel room priced at a reasonable rate, only to encounter a larger or much different rate at checkout?

Beyond regular taxes levied by the state in Michigan, there is another tier of fees that most people don’t know about–hotel taxes, or in terms of the law, assessment fees.

The primary reason for these taxes is to generate revenue at the cost of non-constituents for tourism and affiliate marketing programs. This is done by charging a percentage on a hotel room or transient facility.

The funding for these assessments came into existence with the public act of 1974, which enabled counties to exercise a tax on transient facilities or hotel rooms, popularly named the Accommodations Tax.

This tax was further developed and was made to be the primary funding source for the Public Act of 1980, named Community Convention or Tourism Marketing Act, which today is the main purpose for the assessment and this article.

The Michigan legislature of 1980 found that “Tourism is a major source of employment, income, and tax revenues in this state, and the expansion of the tourism industry is vital to the growth of the state’s economy.”

Further, the legislature understood that no individual business could manage the large fixed costs or potential free riding imposed by running national ad campaigns, and that “State oversight and resources are needed to implement a coordinated and effective marketing program.”

Tourism boards or community convention bureaus are organized based on municipalities and counties with populations of 650,000 or less. For instance, Marquette Michigan’s convention bureau is named Travel Marquette, which encompasses Marquette County.

Travel Marquette’s mission statement on their website states, “Thank you for your interest in Marquette, Michigan. Travel Marquette assists journalists with travel stories about Marquette County by providing materials, developing itineraries, suggesting attractions, and coordinating interviews. We are able to offer further assistance that can include media rates or other travel assistance on a case-by-case basis.”

This is typical of a convention bureau’s mission statement with differences ranging by the particular area’s natural resources, attractions and history. Their travel brochure, a hefty 70 page booklet, consists of popular restaurants, travel spots, locally-made products, advertisements for adjacent districts such as Keweenaw county and travel ideas for Marquette and the Upper Peninsula.

These conventions or bureaus are made up of a local board of members who control the organization and vote on its policy. Members are elected by the bureau itself–stated in the original clause of the act is “A majority of the members of a board shall be owners of transient facilities.”

Meaning, local hotel owners are supposed to make up the majority of the board.

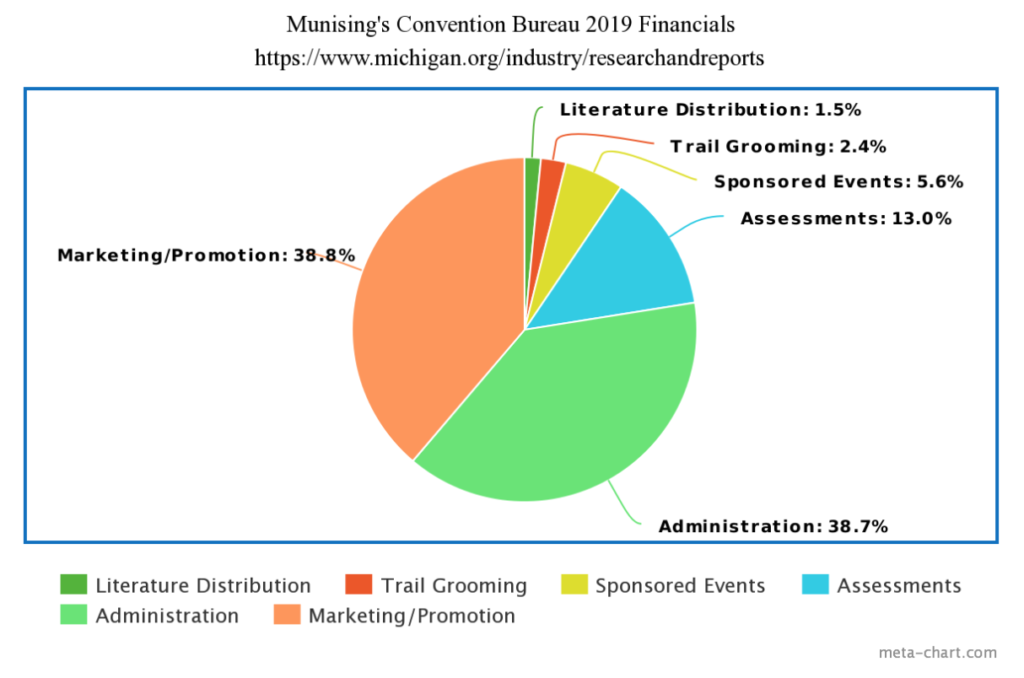

The bureau itself is a nonprofit corporation, but since the assessment is mandated by law, bureaus do not have to share specific financials with the public. However, broad audits are available through the Travel Michigan website for each of the 47 bureaus; the statements include expenditures, administrative costs and other financials.

Although each convention meeting is private, citizens and interested parties can be invited to bureau meetings. Each individual bureau at its founding, as many corporations or business entities do, sets out its own bylaws by which the bureau is to be run.

Bylaws are similar from each to the next, but not the same. An example of a bylaw would be how to elect a president or other managerial roles, such as treasurer. Bylaws also set out the rules by which voting and meetings are to take place.

For instance, the Keweenaw Convention & Visitors Bureau–Keweenaw and Houghton Counties’ combined bureau–has a maximum of eleven members, all owners or managers of hotels. While the maximum number of seats on the convention is eleven, they have a hard time keeping that many on the board since the work is voluntary.

Another bylaw specific to the Keweenaw’s bureau is that since it is made up of two counties, the board must consist of four members from each county.

An interesting fact about bureaus and their respective areas is that when a major change is to take place, all hotels from the district vote on the issue, number of votes are allocated by number of hotel rooms.

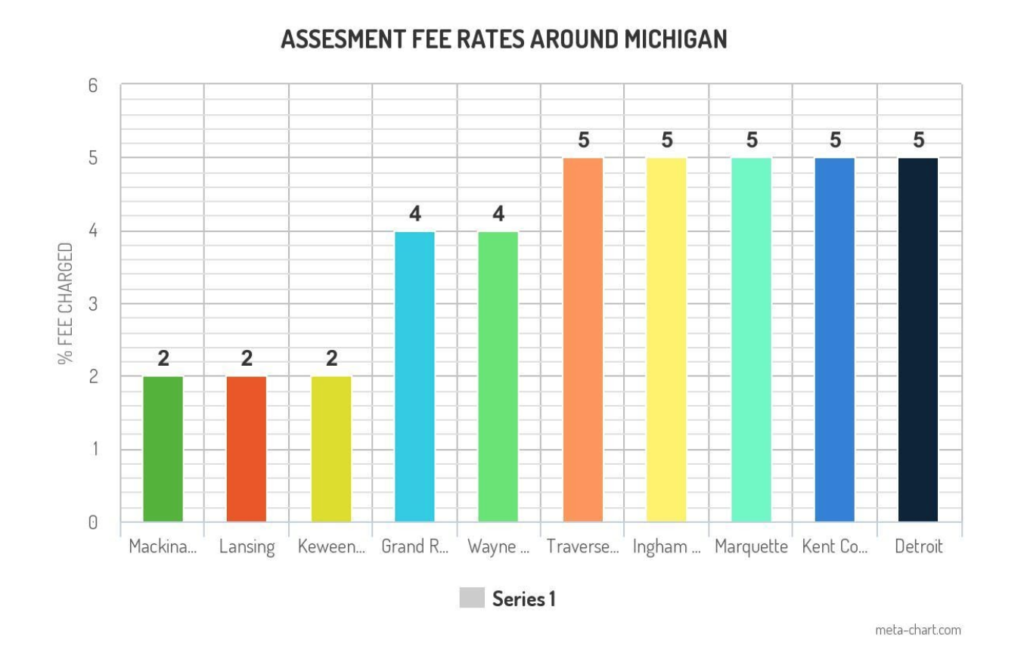

An example of a major change would be an increase in the percentage assessment fee charged by the act. Outlined in the 1980 Public Act is a maximum on the percent of a hotel room that an assessment fee can take–five-percent. This fee is collected by a third-party-certified public accountant. Fees are then due monthly to the accounting firm. The pooled funds are then given back to the bureau for allocation and spending.

The only way to confirm if a hotel is paying its proper fees is to check them against their filed state taxes. The firm that collects the fee is set up by the board of directors, this is done to alleviate work that the bureau would have to conduct itself and to exclude the board from seeing specific financials of the district.

Individual bureaus can hire employees to help with administrative work, so long as the funds are approved. Bureaus according to public audits spend anywhere from 20-40% on administration and operation costs. Any financials that the board approves of has to adhere to guidelines set out in the original act and its amendments.

Bureaus are supposed to have a main advertising strategy or long-term goal, denoted as a “Master Plan” in the original act. Each Bureau meets at least annually to “coordinate their marketing program activities and annual marketing plan activities with the master plan with a goal of maximizing the impact of tourism and convention business on the economy of this state.” The specific master plans and annual reports can be found on Travel Michigan’s website.

If the board of directors find the proposed spending or plan to be agreeable and the vote is passed, any funds and allocation of resources must be approved by the vice president of Travel Michigan. This is done to make sure that the spending and allocation of resources adheres to the guidelines set out by the act and contribute to the greater “Master Plan” of the district and state as a whole.

The current vice president of Travel Michigan is David Lorenz. Travel Michigan is the state’s own travel agency–they perform functions similar to that of individual bureaus, but for the state as a whole. In a 2018 report, Travel Michigan found that Pure Michigan–one of their most successful ad campaigns–influenced 2.1 million trips, generated $153 million in state tax revenue, leading to a tax ROI of $9.28 for every one dollar spent.

On top of the maximum 5% in the Upper Peninsula there is a 1% fee which is allocated towards the Upper Peninsula Travel & Recreation Association (UPTRA), an organization established in 1911 with the mission being “promoting all of the tourism products and services in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Through our marketing efforts and information that we provide the consumer we allow people to plan an outstanding vacation to one of our country’s great natural regions.”

This is like a UP-specific bureau; it provides similar services but has its own place in the law. A key difference being UPTRA does not have to publish financials as other bureaus do.

The Public Act has been reformed to better fit the evolving climate of the digital age, and has been made to provide more oversight in terms of spending and allocation. Ultimately, the state sums up the spirit of this tax in its original finding for the act: “This state can best undertake effective tourism marketing through the coordinated efforts of existing state government agencies in tourism promotion and private convention and tourism promotional bureaus who are better able than state agencies to market and promote their unique assessment districts.”

Each district enjoys a fair amount of discretion when allocating its funds, being able to capitalize on its respective specialization. The funds also are not taken away from broader marketing plans of the state, so there is no tradeoff between state and local.

The act and its amendments are quite thorough, although they leave the area of services like AirBnB out of the picture. Rentals or similar services can opt into bureaus and enjoy membership benefits, but ultimately can “free ride” the program.

Chicago implements a mandatory fee for services such as AirBnB and an additional 4.5% on top of the base. The act and its place in the law is unique for a tax–its constituents are made of travelers who visit the respective region and are a changing base. For the tenure of its existence it has gone through some scrutiny but ultimately most people don’t know they pay it or what it is.

As the U.S. grows to a more service-orientated economy, the boards will hopefully continue to promote their district and maximize the effect of tourism on the state as a whole.