The Impact of Child Care in Rural Upper Peninsula and Compared to Three Urban Counties in Lower Michigan

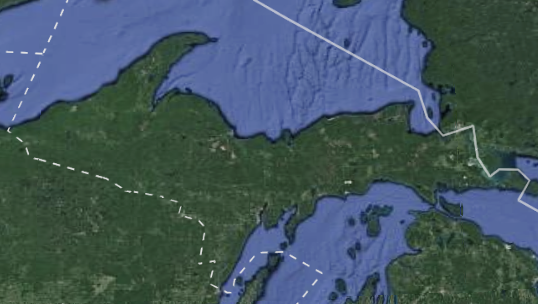

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, though facing much higher rates of poverty and unemployment, sees comparable costs for child care when compared to Lower Michigan. This economic inequity has been examined through the U.P.’s six largest counties: Marquette, Dickinson, Chippewa, Houghton, Delta, and Menominee.

The average monthly cost for child care in these counties is $752.04, the median household income is $45,081, and the statewide median household income is $52,668.00. The average percentage of people living in poverty in the U.P. is 16.0%, compared to 15.6% statewide average.

The statewide average for child care is $823.04 per month. This is easy to understand when examining the childcare landscape of Lower Michigan. Looking at the downstate urban counties of Oakland, Macomb, and Ingham, the average monthly cost is $975.92. These counties in Southeastern, Central, and Western Michigan represent three vastly different socioeconomic environments. The level of population below the poverty line in these counties is 13.9%. However, the averaged median income of these counties is a hulking $12,648 higher than the U.P. counties, at $57,729 annually.

Despite the base costs of child care increasing south of the Mackinac Bridge, the Upper Peninsula citizen devotes, on average, 20.0% of their annual salary to state-licensed child care. The four Southern Michigan urban counties pay out an average of 17.1%. This only accounts for the care of a single child–meaning many U.P. families already facing financial difficulties are paying anywhere from $9,000 to $25,000 annually to acquire full- or part-time care.

The economic pressures facing citizens in the U.P is compounded by its location. Residents are often saddled with much higher utility costs than that experienced by Lower Michigan due to much harsher and longer winters. On account of the area’s vast terrain and a population of only 300,000, there are less options for child care. This, naturally, results in parents travelling upwards of 15 miles one way to provide their children with comprehensive care. Though transportation costs have not been examined in the scope of this study, they represent yet another hindrance to parents seeking safe, reputable services.

Many families in the Upper Peninsula have sought to remedy this through in-home care, both licensed and unlicensed. The unlicensed sector of this industry is particularly difficult to monitor and evaluate, purely due to the fact that these individuals rarely advertise their services. In anecdotal research, parents have engaged the employment of teenagers, elderly neighbors, and cash-strapped college students. Some of these providers have undergone background checks and first aid training, for others it is unclear. The common denominator among them is

that they receive unreported, untaxed income—they are paid under the table. Therefore, any objective attempt to study such services falls short.

The final, and perhaps most detrimental, factor in the Upper Peninsula’s childcare struggles are a result of its rural setting and low population. Within the urban areas of the Lower Peninsula, many assistance programs have been enacted to assist families with the financial burden of child care. These range from fully-funded state assistance to private religious organizations opening their nurseries to children from low-income homes. With a few key exceptions, these initiatives are effectively nonexistent in the Upper Peninsula. The only organized, far-reaching solution of this kind is the Military Child Care Fee Assistance program. This is a federally-funded program that offers free or reduced-cost child care to active duty service members and veterans. While this stands to serve the U.P.’s large population of veterans, it does not address the struggles of non-military families.

The issue of the cost and availability of child care in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is under-reported and intertwined with other socioeconomic factors in the region. Michigan, as a whole, faces the financial burdens of expensive care for their children. However, these services come at a much higher price to the residents of the Upper Peninsula. Awareness surrounding these issues is required in order to begin to address them.

DATA:

Upper Peninsula

| County | Population | Median Household Income | Percentage of People living in Poverty |

| Marquette | 67,077 | $48,491 | 16.4% |

| Dickinson | 26,168 | $45,618 | 15.2% |

| Chippewa | 37,517 | $44,030 | 17.1% |

| Houghton | 36,628 | $41,379 | 21.4% |

| Delta | 35,784 | $46,490 | 12.4% |

| Menominee | 24,029 | $44,480 | 13.5% |

| Average | 37,867 | $45,081 | 16.0% |

Lower Peninsula

| County | Population | Median Household Income | Percentage of people living in poverty |

| Oakland | 1,259,201 | $76,387 | 8.2% |

| Macomb | 874,759 | $60,466 | 11.0% |

| Ingham | 292,735 | $50,940 | 18.1% |

| Average | 808,898.3 | $63,597.6 | 12.4% |

State and National Averages

| State Average | NA | $52,668 | 15.6% |

| National Average | NA | $57,652 | 11.8% |

CHILD CARE COSTS

Upper Peninsula

| County | Cost per Month for Full-Time Care per Child | Cost per Month for Part-Time Care (approx. 15 full days or 30 half- days) per Child |

| Marquette | $662.00 | $250.00 |

| Dickinson | $730.00 | $220.00 |

| Chippewa | $834.50 | $409.75 |

| Houghton | $856.75 | $276.00 |

| Delta | $779.00 | $318.00 |

| Menominee | $650.00 | $325.00 |

| Average | $752.04 |

Lower Peninsula

| County | Cost per Month for Full-Time Care per Child | Cost per Month for Part-Time Care (approx. 15 full days or 30 half- days) per Child |

| Oakland | $1,116.00 | $660.00 |

| Macomb | $941.60 | $540 |

| Ingham | $870.16 | $646.40 |

| Average | $975.92 |

State and National Averages

| State Average | $823.04 | |

| National Average | $1,712.50 |

Breakdown

Marquette County:

- 64 Child-Care Providers that have been licensed by the State of Michigan’s Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs

- 33- Child- Care Centers

- 18- Family Care Homes (Capacity 1-6)

- 13- Child- Care Group Homes (Capacity 7-12)

(All Above Data Provided by the State of Michigan Child Care Search)

Dickinson County:

- 30 Child-Care Providers that have been licensed by the State of Michigan’s Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs

- 15- Child-Care Centers

- 6- Family Care Homes (Capacity 1-6)

- 9- Child- Care Group Homes (Capacity 7-12)

(All Above Data Provided by the State of Michigan Child Care Search)

Chippewa County:

- 44 Child-Care Providers that have been licensed by the State of Michigan’s Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs

- 17- Child-Care Centers

- 15- Family Care Homes (Capacity 1-6)

- 12- Child-Care Group Homes (Capacity 7-12)

(All Above Data Provided by the State of Michigan Child Care Search)

Houghton County:

- 40 Child-Care Providers that have been licensed by the State of Michigan’s Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs

- 20- Child-Care Centers

- 13- Family Care Homes (Capacity 1-6)

- 7- Child-Care Group Homes (Capacity 7-12)

(All Above Data Provided by the State of Michigan Child Care Search)

Delta County:

- 31 Child-Care Providers that have been licensed by the State of Michigan’s Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs

- 21- Child-Care Centers

- 7- Family Care Homes (Capacity 1-6)

- 3- Child-Care Group Homes (Capacity 7-12)

(All Above Data Provided by the State of Michigan Child Care Search)

Menominee County:

- 22 Child-Care Providers that have been licensed by the State of Michigan’s Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs

- 10- Child-Care Centers

- 5- Family Care Homes (Capacity 1-6)

- 7- Child-Care Group Homes (Capacity 7-12)

(All Above Data Provided by the State of Michigan Child Care Search)