Housing Rental Cost Dynamics in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula

Housing prices in the US have been increasing at an average rate of 7% over the last seven years. The Upper Peninsula has not been immune to this trend, with housing prices lurching higher across the region. This study looks at the pricing dynamics of housing across several counties in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, which have relatively large populations for the UP, and feature a significant population of students and/or tourists.

Pricing dynamics are explored by looking at trends such as rental housing, general housing prices and how this compares with GDP, population growth, and other economic factors to set those changes in a broader economic context. A review of these housing pricing dynamics leads to exploration into the significance of these dynamics on local communities and the broader UP economy. This study also attempts to contribute to the conversation on how changes in housing and rental prices can impact residents and the future economic health of the UP.

The data comes from several sources. The median rental housing prices come from two places: The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the United States Census Bureau; median housing sale price data comes from Zillow, an online real estate marketplace company. Economic data comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis; population data comes from the Census Bureau. Where incomplete or unavailable, data for 2020 and 2021 is estimated through simple linear modeling and is marked accordingly

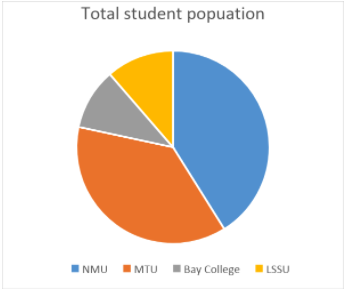

The four areas of the UP analyzed are: Marquette, Houghton, Chippewa, and Delta County. These are areas in the UP that are influenced by academic institutions located in these regions. Michigan Technological University in Houghton County, Northern Michigan University in Marquette County, Lake Superior State University in Chippewa County, and Bay de Noc Community College in Delta County create unique dynamics due to a transitory student and incoming faculty population.

Bay College may seem like an outlier from the list, but it has been a growing college, and despite its smaller size it also casts an influence on the housing economy in Delta County. In addition to a broader economic impact related to the needs of students and their visiting families, the cities featured in this study were selected as the presence of a transient college population often translates into a typically higher demand for housing.

When analyzing the housing dynamics of cities with significant college populations, it is important to include rental housing in the evaluation. Due to availability as well as affordability, most students rely on rental properties to secure housing outside of campus. The analysis on rentals will primarily focus on studio and four-bedroom rentals, as these tend to be the most affordable to a person with a smaller budget, due to the small size of the studio and ability to rent a room out of a larger house.

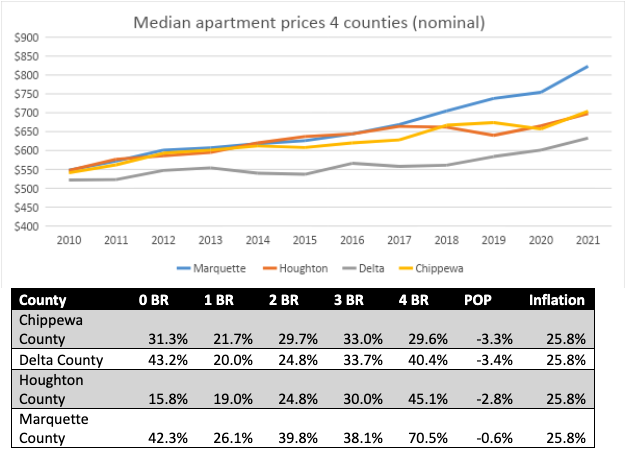

As evidenced by the data, rental prices have been steadily increasing year over year in all four studied locations. That said, Marquette has seen the most significant increase in rental cost during the last four years.

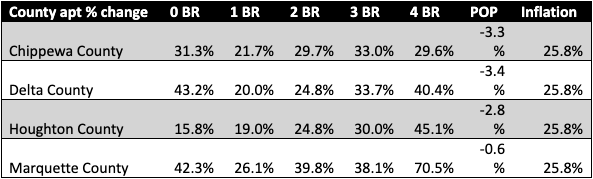

Throughout the four counties, the median rental housing prices have increased over the past 11 years with housing prices increasing over the rate of inflation, the average per year being 2.19% in all counties except for Delta. Marquette saw the largest increase of 50% for the median rental price (of all bedroom sizes), and Delta saw the smallest increase of rent price at 21%, with inflation at 25%.

While an increase in housing prices is broadly observed across the country, a deeper dive into local data provides an indication that price increases for houses indicate variation depending on the size of the house. Across the board, the largest price increase was in Marquette for a four-bedroom rental, featuring a 71% increase in average sales cost since 2010. The four-bedroom sect on its own was the largest-increasing price out of all housing; though this might be impacted (especially Marquette) by the COVID-19 pandemic. Marquette, Delta, and Chippewa County have seen a 28%, 9%, and 8% (respectfully) increase in four-bedroom apartment prices.

Zero bedroom, or studio rentals, in Marquette and Delta, also saw significant price increases in the past eleven years, though the increase was relatively comparable to the price increases for Chippewa and Houghton. The percent price increases were 43% in Delta and 42% in Marquette. One-bedroom rental prices also fell slightly below average compared to the overall median rental price, where it was the lowest price increase compared to the median in Marquette County.

The price paid for two-bedroom rentals saw an increase slightly below the median in all counties except Delta, where the average two-bedroom apartment now costs about $920 which grew at a rate of about 25% (see table below). Three-bedroom rental prices have tended to increase above the rate of the median rental cost for all counties except for Marquette, where the median rental now costs about $1,300 (which is about the price the author is paying for his three-bedroom rental).

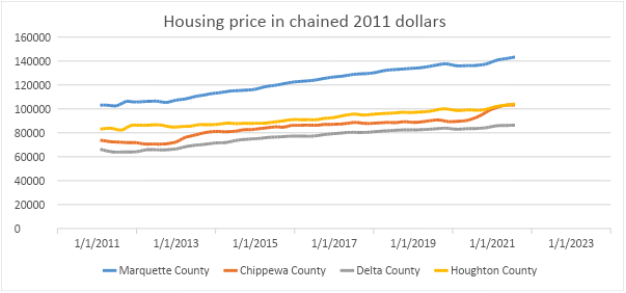

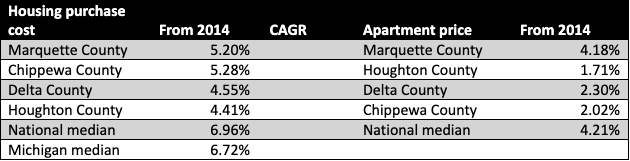

Rental price increases are reflective of a broader market trend in housing that also impacts purchase/mortgaged housing costs. The real estate market handily outpaced the rate of inflation during the past few years both nationally and locally. In all counties studied, housing purchase cost inflation actually increased faster than the price of rentals. Since 2013, across the areas analyzed, property values have increased on average 53%; this was led by Chippewa County at 62%. This high growth rate came with a CAGR of 5.9%. (FOOTNOTE: Compound annual growth rate, CAGR = (beginning value/ ending value)^1/time -1)

Counties across the UP have seen, in real terms, an increase in rental, and general housing prices with the sharpest increases in Marquette, and the lowest increases in Delta county. This means in real terms, the majority of counties saw a real increase in the costs of housing, over the cost of wages. These rates of change were also greater than the increase in GDP.

Applying this data to the national and state context allows for further interesting dynamics to be observed. Despite regional price increases, since 2014 the US housing market has grown, in nominal terms, at a greater rate than the housing market in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, or any UP county, for both the rental market and the general housing market. At the state level, while there was no rental-specific data available, it seems that Michigan’s general housing market has also grown at a greater rate than that of the UP, though still under the US median. This data only looks at purely the county level, so it is possible there were towns, such as Marquette micropolitan area, or Houghton proper, that grew at a quicker rate than the national average. Though the increase was under what is seen across the US, it still impacts the UP strongly. With a declining population, more stagnant GDP growth, housing increases can have an outsized effect on the population at large.

One reason for housing prices to have increased is because of an increased number of people moving to the UP for various reasons–this can create demand for housing. Increased demand in housing also tends to affect the rental housing market, if housing is looked at as a leading indicator1 the price tends to change faster than the rent price. However, before people invest a significant amount of money in a home they may want to test out the area with a rental. Meaning that rental housing increases can also be looked at as a leading indicator.

Increases in housing prices can have ripple effects across the community, one of the biggest effects is on workforce housing. Workforce housing is defined as housing costing between 80% and 120% of the median income of an area. This is housing geared towards people who make above the amount where they would qualify for subsidies and are some of the most sensitive to housing price increases as they may rise faster than wages. Alongside workforce housing, college towns have another demographic making up a significant proportion of the economic base of the town: college students.

College students tend to play an important role in smaller town economics and housing dynamics. Through friends and extended families, they bring in people who may not typically come to an area for work or tourism and spend money that may have been made outside the area. Relationships built during college can also come into play later in an individual’s life, drawing them back to the area upon retirement. This can bring people looking to buy second homes in the area (the snowbird), or give them an area where they have a former connection when they have a period of remote work. All these things can drive up housing prices, the first, being geared towards the rental market, which can, in turn, increase property values through returns on investment. The latter increases property values, which can in turn increase rents by increasing demand in a typically fixed housing market. This almost perpetually propelling increase in housing costs can eventually be detrimental to an area. When more of a household’s income is spent on necessities such as housing, transportation, and food, it leaves less money available for discretionary spending, which can harm the health of an area’s economy, or at least exclude entire groups of individuals from participating in and benefiting from a changing mix of businesses and services.

In the longer term, as housing prices in an area increase, even if that increase is originally driven by college populations, it can eventually decrease the affordability of a college. At a mid-sized public university such as Northern Michigan University, housing and food costs are around 50% of the total cost of attending the university. Further increases in this expense may lead students to find another college that fits more within their budget. As city housing prices do not affect those living in the dorms as much as those who are living off campus; it can cause a decrease in people returning to campus after moving out of university provided housing. Students priced out of off-campus housing may find it more advantageous to move to an area where housing is more accessible, possibly leading to a drop-in enrollment, and a decline in graduation rates; which can have a delayed effect on the broader economy of a town. This is something that is happening currently in the UP with observed migrations between Marquette and Houghton.

For university populations, the impact of housing price increases is not limited to students but can also significantly impact faculty recruitment and potentially retention. One issue currently facing Northern Michigan University, is that some of the junior faculty members are having trouble affording starter housing in the area. This can cause a decrease in the talent that the school can attract and may eventually be a factor influencing faculty retention.

In considering the pricing dynamics of college towns, and those present in the UP specifically, it is interesting to explore how the nascence of remote work is further propelling these dynamics. College towns, including those in the UP are enticing to live in remote workers seeking recreational areas offering both summer and winter activities. This influx of remote workers can also be a result of the colleges themselves–as universities hire highly-educated individuals for teaching and research jobs, many of these individuals move to the area with educated partners and spouses. For those spouses, local career choices are limited and so many bring with them or seek out remote job options effectively doubling or even further increasing their household incomes. This outside income further increases the pressure on a tight housing market as these households can outbid and outcompete locally-employed or one-salary households and while unintentionally still help fuel the housing cost inflation.

It is important to mention that there are also many benefits resulting from local economic growth as well as even housing or rental unit price increases, but an analysis of these benefits was intentionally left out of this study. This is due to the fact that the objective was to highlight the scale and potential negative consequences of housing price increases to help spotlight the need for affordable housing options for students, new faculty, but also legacy local residents who may simply face getting priced out of their homes or rentals. That in turn could have long term detrimental consequences to many Upper Peninsula communities, but frankly also negatively impact the individuals and organizations that are currently benefiting from increased rental and housing costs. As Marquette, Houghton, Delta, and Chippewa counties continue growing in the near future, it is important for these localities to consider sustainable growth policies to protect economically sensitive populations, but in the long term to solidify and maintain the benefits of this growth.

Footnotes

1As the housing market is more fixed and has less liquid supply (this may be different in an area that does not have as high of rental demand as Marquette does).