When it Rains It Pours: Climate Change in the Upper Peninsula

This summer brought deadly floods to Eastern Kentucky and St. Louis, while sweltering heat has made headlines in the Pacific Northwest and Southern Plains. Climate scientists link these extreme weather events to global climate change.

Michigan, and the surrounding Great Lakes states, are not immune to such effects, with heavy rainfall increasing in intensity and frequency throughout the region. This article focuses on two manifestations of climate change for the Upper Peninsula: the increase in extreme precipitation events and the number of days that exceed 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

The data for this analysis is from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) MiTracking Program through a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

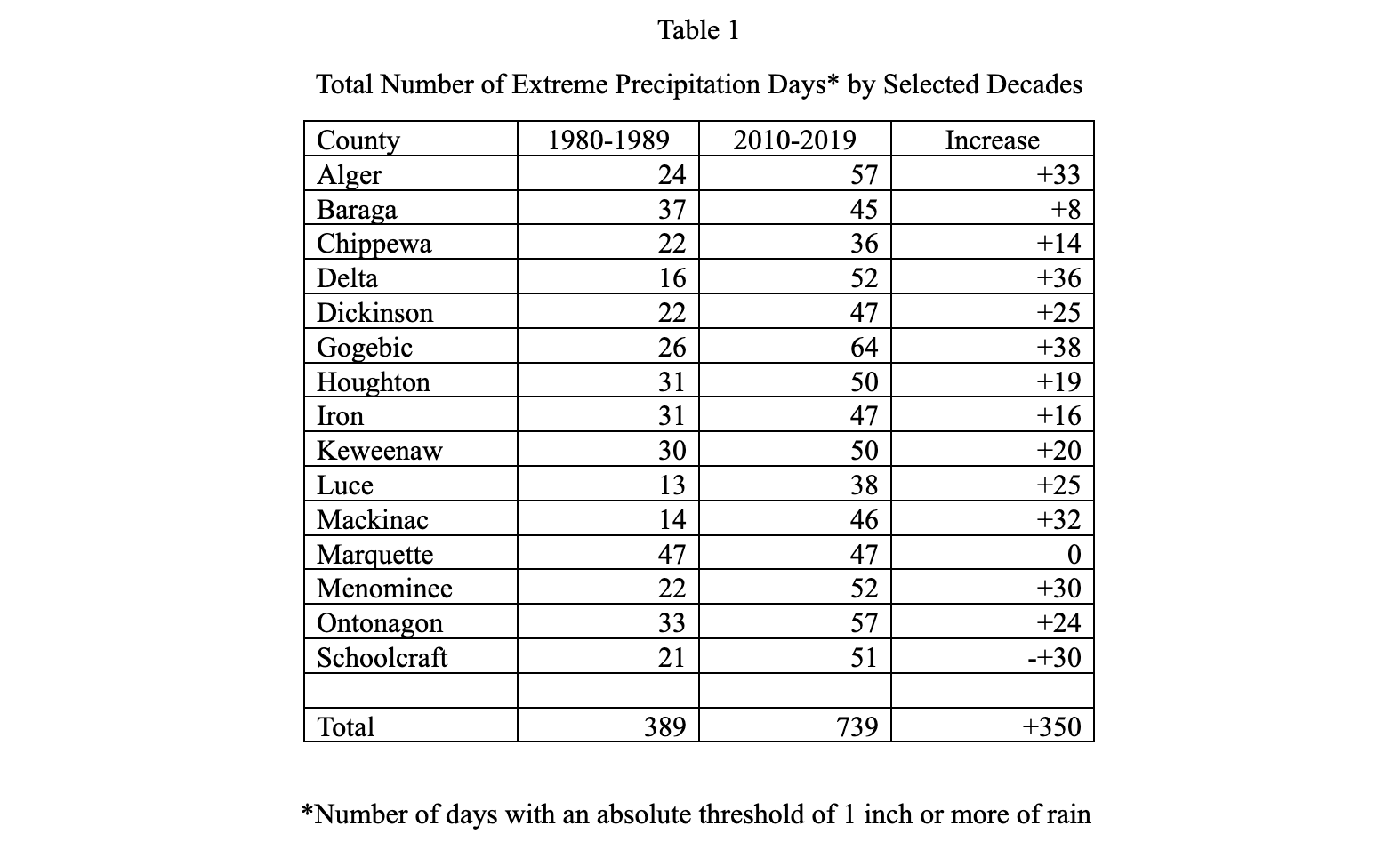

As the data from Table 1 indicates, the number of days with an absolute threshold of 1 inch or more of rain has increased across the Upper Peninsula, from 389 during the 1980s, to 739 for the period between 2010 and 2019; an increase of 90%. The counties with the largest absolute increases (plus 30 or more days) for these kinds of precipitation events are scattered across the entire region and include Gogebic, Delta, Mackinac, Alger, Menominee and Schoolcraft.

The consequences of such rainfall amounts are illustrated by a recent storm that hit Marquette County on May 12, 2022. A record daily rainfall amount of 1.62 inches produced flash floods, widespread damage to local roads, and a state Emergency declaration. Nearly two decades earlier, in May 2003 the area surrounding the Silver Lake Dam in Marquette County received 4-5 inches of rain in a 48-hour period.

The dam meant to hold back water failed and released more than 9 billion gallons of water downstream into Lake Superior. No lives were lost but the floodwaters caused more than a $100 million in property damages, and an evacuation of residents in the northern part of the city of Marquette.

In June 2018, the so-called Father’s Day Flood in Houghton was the result of the area receiving 7 inches of rain in a three-hour period. The flash floods that resulted from the deluge destroyed homes and businesses causing over $40 million in damages to the county’s roads, while the state’s Department of Natural Resources reported over $20 million in damages to its trail system.

The damage from the storm brought a federal disaster declaration for Houghton, Baraga and Menominee counties. The federal government has declared 12 such climate-related disasters in the Upper Peninsula between 1989 and 2017, according to data compiled from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Baraga, Gogebic, Houghton, Marquette and Ontonagon each had two declarations, while Keweenaw and Iron counties had one each.

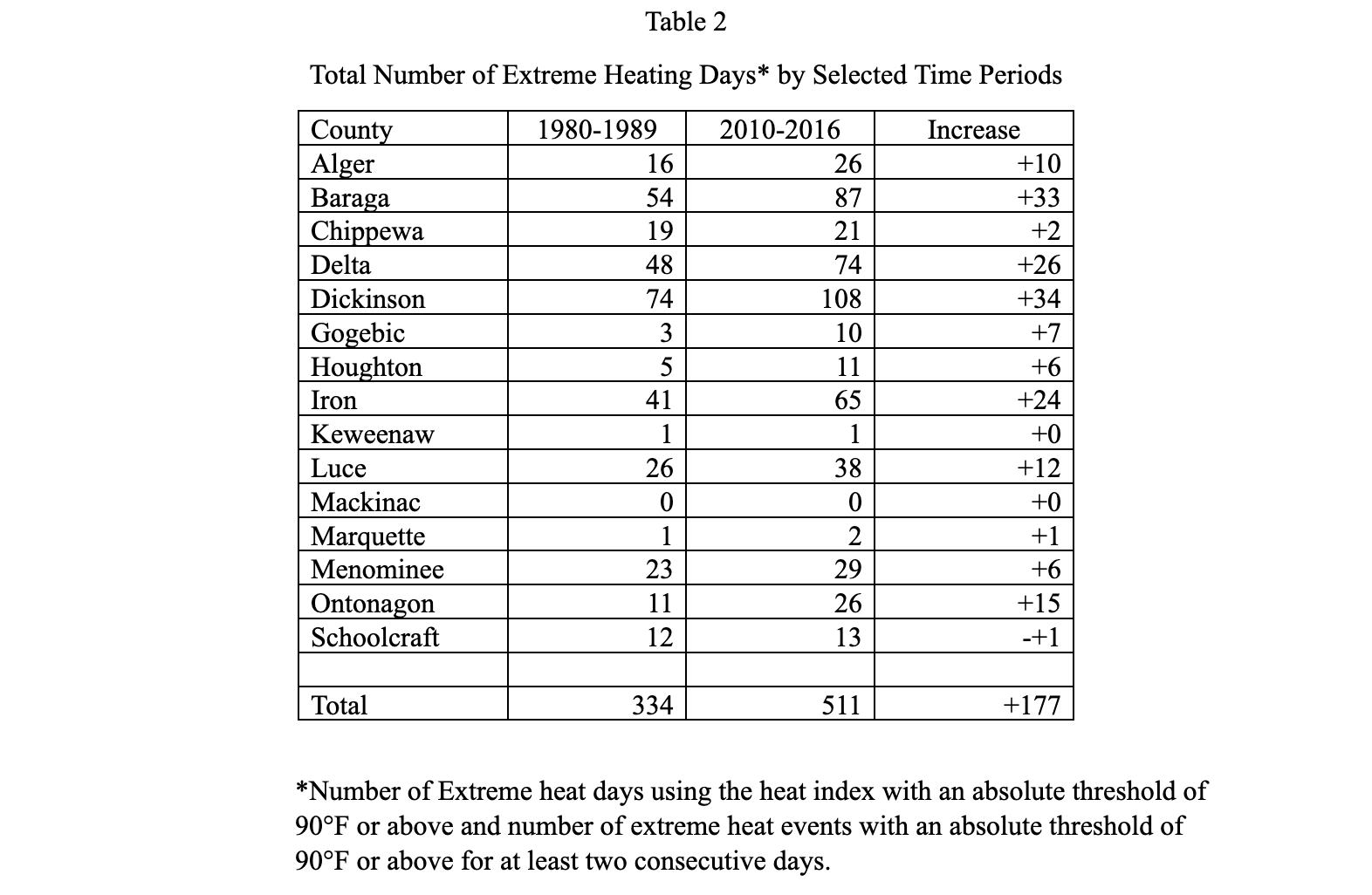

The number of extreme heating days in the UP has increased by 50 percent over the past 40 years. (Table 2). However, it is important to recognize that the 2010-16 period is three years shorter than the 1980-89 period, so the increase in frequency is even higher than 50%. The counties experiencing the most extreme heating days are Dickinson, Baraga, Delta, and Iron counties, while counties which have an extensive shoreline with either Lake Michigan or Lake Superior tend to have the fewest number of days, as they benefit from the cooling effect of summer onshore breezes.

A recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found an increase in days with temperatures of 90 degrees or higher was associated with increased mortality. The people most vulnerable to the effects of climate change include those with low income, Indigenous peoples, children and pregnant women, older adults, persons with disabilities, and persons with preexisting or chronic medical conditions.

Neighborhoods at Risk is an online platform that enables researchers to identify community areas where climate mitigation efforts should be focused. Tree cover plays an important role in reducing the direct heating effects of the sun, yet there are parts of cities where there are few trees.

In the city of Marquette, the population that is most vulnerable to the effects of climate change is concentrated in the northern section of the city along Presque Isle Avenue, yet two-thirds of the area lacks tree cover. In downtown Sault Ste Marie, where over 4,000 people live, over 96% of the area lacks a tree canopy, and over a third of the area is covered by an impervious surface (e.g., parking lots) which increases its vulnerability to flooding from sudden downpours. In Escanaba, the city’s most vulnerable population is concentrated on its northside, in an area that has a limited tree canopy.

Despite the increases in extreme weather events, the Great Lakes region is frequently touted as a destination for people wanting to escape rising sea levels or extreme conditions like drought, heat waves and wildfire smoke – so-called climate migrants. In a recent article published in Crains Chicago Business, Marquette City Commissioner Jenn Hill is quoted as saying there is some evidence of climate transplants from California settling in the city, while a recent Marquette newcomer told the article’s author that she would not have considered a move to the Upper Peninsula from New Orleans were it not for Louisiana’s increasing floods.

Looking ahead it seems more than likely that as environmental conditions deteriorate in other parts of the United States, the Upper Peninsula is likely to be seen as a safe climate haven for those with the means to move to the region. This influx of population, while providing a welcome boost to the area’s population, is likely to exacerbate a shortage of affordable housing for local residents.

In the meantime, UP communities need to account for extreme weather in their planning to ensure the area is in fact a safe place for all.

Climate change is a catastrophe and we’re just getting started. The UP to-do list:

1. Survey active & fallow land available for farming. Food shortages will be rising. Talk with Amish / Mennonite groups about relocating.

2. Begin labor training & recruitment planning to increase younger working age population that will be needed to support expanding population. From basic service work to skilled trades.

3. Develop energy efficient housing and transportation infrastructure that anticipates cutting energy use. Growth should be concentrated around population centers that have state supported higher education.

4. Understand profile of climigrants who are suited to life in the UP. This place has potential but only for those who can adapt to the UP. And let’s get some diversity among future residents.

5. Organize regional planning and development structure. Way too many inefficient, small units of government in UP who don’t like to cooperate and coordinate.

Michael and John,

This article was very well done!

I am the Executive Director of the West Michigan Food Processing Association (WMFPA), supporting food companies and farmers to learn the importance of sustainable economic development, innovation and rural communities engagement.

We recently launched the WMFPA Sustainability Blog Series: https://www.westmichfoodprocessingassn.com/blog

Would you be interested in writing a blog for our series? I have some ideas for area of focus of the blog.

Here is my contact information below:.

Thanks so much,

Marty Gerencer

Executive Director, WMFPA

Mobile: 231/638-2981

Email: marty.gerencer@gmail.com

Website: https://www.westmichfoodprocessingassn.com/

Well, It is all in how you spin it. Looking at days with more than 1″ of precipitation may make it seem like there is lots more rain, but if you refer to the NOAA data here https://glisa.umich.edu/media/files/MarquetteMI_Climatology.pdf it seems like the overall amount of rain has remained about the same in Marquette and has actually decreased in the western UP during the period 1962-2014. The data there does not cover the period from 2014-2022, so there could be some differences. Also, let me say that characterizing rainfall over 1″ as “Extreme Precipitation Days” is rather disingenuous. Although there is no formal definition of the term “extreme rainfall” David Novak at NOAA says that a good benchmark is when a month’s worth of rain falls during one day. In Marquette, for example, the average monthly precipitation is about 3″, so an “extreme” precipitation metric would be 3″, not 1″. Even looking at the “extreme days” described in the article, may not tell us much about climate change. Are we just getting heavier rainfall on the days that it does rain, leaving other days dry? (Actually, that might be an improvement on lots of cloudy days when we just get a sprinkle of rain.) I am not saying this to dispute climate change. Only to put the brakes on data that can be interpreted incorrectly.

Thank you. Neither on one of these guys are climate experts.

The big bear in the tent of global warming is over population. Few want to talk about it or consider it. Our fragile world has far too many humans, as does the USA. The UP has enough, and we certainly don’t need to encourage more to come, although that will inexorably happen anyway.